As our society evolves so, too, do the health challenges we face.

UAB Medicine is at the forefront of addressing emerging and evolving health issues with the introduction of new clinics and programs designed to meet the dynamic needs of patients at every stage of life. Among these are the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic, which responds to the increased prevalence of smell and taste disorders following the COVID-19 pandemic, providing specialized care and innovative treatment options. The UAB Staging Transition for Every Patient (STEP) Program ensures that adolescents transitioning from pediatric to adult health care receive seamless, comprehensive care, bridging a crucial gap in patient management. Additionally, the UAB Brain Aging and Memory Hub offers holistic services for those experiencing cognitive decline, integrating advanced research and personalized care to support individuals and families navigating the complexities of aging and memory loss. These initiatives underscore UAB Medicine's commitment to pioneering solutions for contemporary health challenges, ensuring patients receive the highest quality of care tailored to their specific needs.

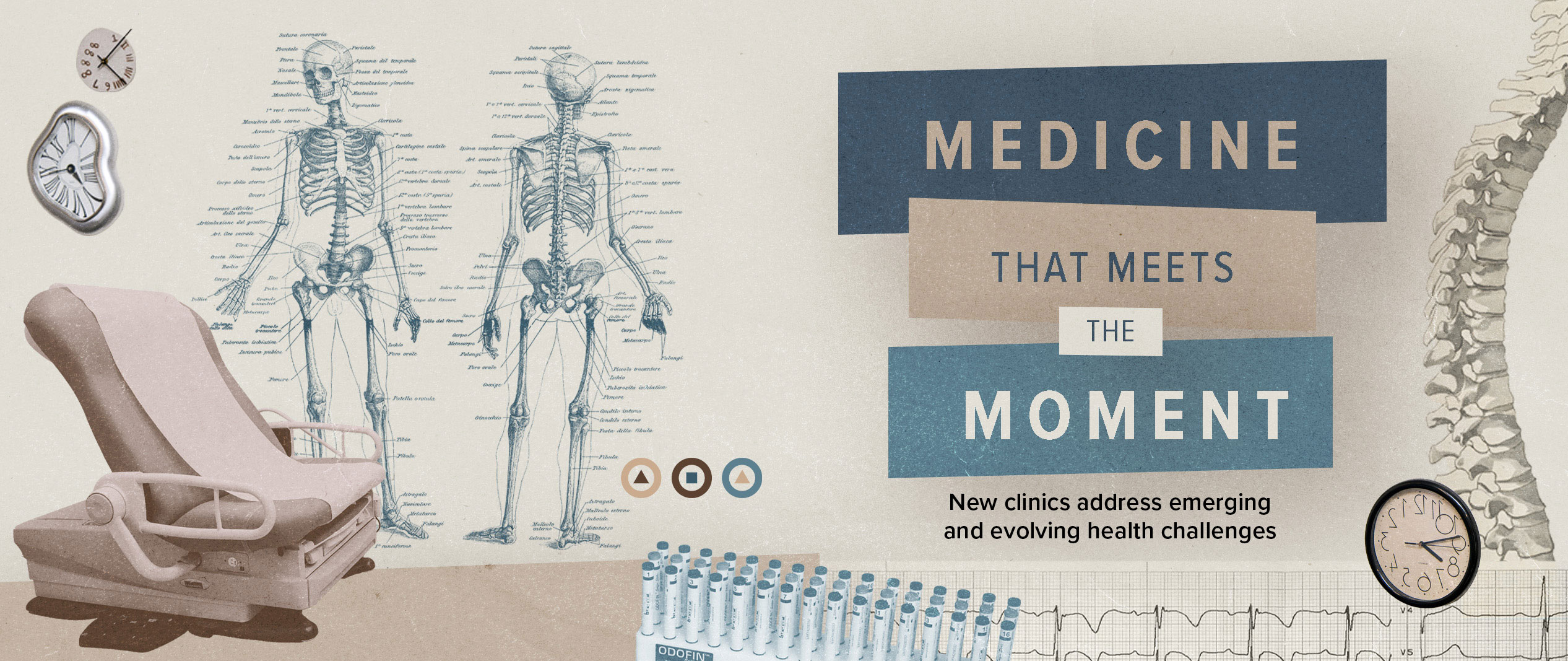

Do-Yeon Cho, M.D., (left) and Carly Bramel, P.A., (right) run the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic.

Passing the smell test

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, at least 500,000 Alabamians have experienced extended smell and taste loss, according to Do-Yeon Cho, M.D., director of the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic and a professor in the Department of Otolaryngology. The clinic, which opened in January 2023 and is thought to be the first specialized clinic in Alabama for patients with olfactory dysfunction, has seen a high volume of patients, with appointments booked far in advance. Luckily, the outlook for most patients is ultimately positive. “After two years, about 80 to 90 percent recover,” Cho said.

COVID and the media attention around COVID smell loss have brought more people to clinics such as Cho’s, but that does not mean every patient’s smell loss can be attributed to COVID, even if a COVID infection was the first time they noticed it.

“I examine patients every time they come in,” Cho said. “A lot of patients did indeed lose their sense of smell from COVID, but some have foreign bodies in their noses, and others have large nasal polyps.” These polyps are often the result of allergies. “We have a lot of pollen in Alabama,” Cho said. “Inflammation or nasal polyps can both block the nose and alter the sense of smell.” Treatment in this case is a steroid rinse.

Cho also asks patients about other symptoms. If they have headache or another neurogenic issue, he will often recommend an MRI or CT imaging scan of the brain and, if warranted, a referral to a neurologist. Cho will also talk with patients or caregivers about their family history of Parkinson’s disease or early-onset dementia. “Smell loss can be the first symptom of neurodegenerative disease,” Cho said. If the cause is related to neurodegenerative disease, “Patients will often say they have noticed it for a few years.”

After a physical exam of the nose and a discussion of symptoms and timing, Cho uses threshold discrimination identification (TDI) testing to evaluate the severity of smell loss or dysfunction. “We are probably the only location doing TDI testing in Alabama,” Cho said, calling it the gold standard for testing. Patients smell a series of odors from what look like felt-tip pens. The odors are at various concentrations—the testing gives an objective score measuring the patient’s ability to distinguish smells from one another and to distinguish the intensity of smells.

While researchers continue to debate the underlying reason for smell loss or dysfunction, smell training is helpful for many patients. “Thirty to 40 percent of patients see significant improvement” after smell training, Cho explained. The training helps rebuild the connections between the nose and the brain and helps patients relearn to accurately identify types of smells.

Cho said smell training kits can be assembled using products that are readily available in stores or online. “You can absolutely use essential oils,” he said. “We recommend four smells at a minimum, although more is great.” The recommended categories of smell include a fruity, sweet smell (like lemon), a flowery smell (rose), a spicy smell (clove), and a resinous smell (eucalyptus).

Cho recommends that patients “get in a zen place” of mental calm. They should hold the tube under the nose for 30 seconds and breathe normally, concentrating on the scent before moving on to the others. “Think about the smell, even if you can’t smell that well,” or at all, at first. “Once you can smell it well, move the tube farther away.”

A subset of patients with olfactory dysfunction do not lose their sense of smell. Instead, it is altered, usually for the worse. “Everything smells terrible,” Cho said. For patients suffering from parosmia, smells can be so off-putting that many “are not able to eat or drink, and there can be severe weight loss,” Cho said. “One patient described taking seven showers a day, trying to get rid of the smell.”

The biological cause of parosmia needs more study, but it comes down to “an issue of how certain odors are interpreted in the brain,” Cho said. “We think this may happen when smell nerves are recovering and they go to the wrong parts of the brain and become overactive, firing too much.”

Cho recommends smell training for these patients, but he has also used the anti-seizure medicine gabapentin with significant success. In 2022, Cho published a paper about a small clinical trial in his clinic.Over the course of the trial, gabapentin was prescribed to 12 patients.

Of the nine patients who completed the study, eight showed improvement and six patients (66 percent), all of whom had parosmia with a foul smell, reported significant improvements. “They did really well,” Cho said. “It shows that, in certain people, medications can help.”

– Matt Windsor

(Left to right) Carlie Stein Somerville, M.D., Betsy Hopson, and Snehal Khatri, M.D., help patients with complex diseases of childhood transition to adult care through the UAB Staging Transition for Every Patient (STEP) clinic.

Living Longer, Healthier Lives

“In the first years of my practice, I saw there was a gap for patients between 18 and 21 years old who had complex diseases of childhood like spina bifida or cerebral palsy, which can have a lot of medical and caregiver needs as they grow up,” said Carlie Stein Somerville, M.D.,an associate professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine. “I wanted to help doctors understand how to help these patients and their families. We are so fortunate to have crosswalks from Children’s of Alabama to the ‘adult hospital’ at UAB. I wanted to create a similarly streamlined transition care from one hospital to the other for our most complex patients.”

In partnership with Betsy Hopson, then the program director for the UAB and Children’s of Alabama Spina Bifida Program, Somerville launched the UAB Staging Transition for Every Patient, or STEP, Program, to help patients across the health system make the leap.

“There is a gap when patients transition from pediatric to adult clinics,” Hopson said. “Life changes are happening—they are leaving high school, trying to figure out what comes next, and right in the middle of that you have this transition in medical care, with brand-new doctors. If you look at the data, you see how medical outcomes decline during this time.”

The nationally recognized STEP Program was funded by a grant from UAB’s unique Health Services Foundation General Endowment Fund grants program. “This is an outpatient primary care clinic where patients and their caregivers can meet a multidisciplinary team to work through the pieces of transition,” Somerville said. “The clinic has three med-peds-trained physicians and seven specialists who come to the clinic and see patients.” These include specialists in psychiatry, psychology, pulmonary, endocrinology, neurology, epilepsy, rehabilitation medicine, physical therapy, and social work.

Gathering all these specialists in a single clinic, who can see patients during a single clinic visit, “helps with navigating Birmingham and parking decks and traveling with all the equipment that these patients often require,” Somerville said. “They get coordinated care and connect to all the adult subspecialists they need.

“There are no other programs like this in the region and only a handful in the country,” Somerville said. “Now we are up to 600 patients, and we are seeing patients from all over the state who travel to us to get this level of care.”

The providers have also benefited. “Any doctor who needs help transitioning a complex patient” can work with the STEP clinic, Somerville said. “As someone who has been a primary care doctor myself, my goal is to empower others to be comfortable taking care of these patient populations, to know about STEP and what we offer, and that they can call us.”

Thanks to its success, the STEP Program has spun off a program aimed at the particular needs of a subset of patients. As recently as the early 1980s, people with Down syndrome were not expected to live past 25. Today that number is up to 60 years old. But longer lives come with questions that few doctors or parents know how to answer.

For instance, many of the relatively small number of people with Down syndrome who have lived to age 40 have developed dementia and other Alzheimer’s-like symptoms by then. But the medications doctors use to treat Alzheimer’s are not approved for people this young.

“We hear from parents that this is the thing they worry about the most,” said Snehal Khatri, M.D., associate professor in the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, and medical director of UAB Sparks Pediatrics. With a grant from UAB’s HSF-GEF program, Khatri and Hopson, STEP Program director, are creating a new clinic within the STEP program to focus on care for people with Down syndrome across the lifespan. It is a very different experience in the pediatric world and the adult world ... Insurance changes. What is covered changes. So being thoughtful in planning for these changes early is extremely important.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group publish guidelines from birth to age 21, including lab work, questions to ask, and other milestones to look for as patients age. But “you would be surprised at the number of primary care doctors who don’t know they exist,” Khatri said. “Having a dedicated clinic will improve adherence to medical guidelines for the pediatric patients.”

The link between pediatric and adult services also means that good ideas can be quickly shared. “One of the things that has been successful at Children’s of Alabama is recognizing sensory needs and the development of sensory pathways” for patients with autism, Down syndrome, and other intellectual disabilities, Hopson said. “What STEP has allowed us to do is to put teams and working groups together to determine what successful practices from pediatric care should or could be brought into the adult clinics. When you think about it in terms of lifespan, what makes it work well from 0–18? Why was the family so comfortable? Let’s adopt those practices with the adult patients. And we are also learning from our adult providers when they say things like, ‘I see patients who are 21 and don’t know they can get pregnant.’ That calls for education on the pediatric side. There is a two-way education stream.”

The lifespan model has potential beyond Down syndrome, Khatri points out. “There are so many conditions that we see in pediatrics that don’t have a good home: autism, dual diagnoses. Is this a framework for other conditions that also cross over from the pediatric to the adult world? We aim to find out.”

- By Matt Windsor

(Clockwise from top) Ronald Lazar, Ph.D., Erik Roberson, M.D., Ph.D., and David Geldmacher, M.D., are now providing care and conducting research from the new Brain Aging and Memory Hub at UAB.

Memory Matters

In April 2024, UAB celebrated the opening of the UAB Brain Aging and Memory Hub, a joint effort between the UAB Health System and the Heersink School of Medicine. The nearly 20,000-square-foot Brain Aging and Memory Hub is located on the newly renovated fifth floor of UAB Callahan Eye Hospital.

Today as many as 80,000 Alabamians have possible early signs of memory problems. Additionally, Alzheimer’s disease is ranked second in Alabama’s state mortality rate. The new hub was created to anticipate the increasing needs of an aging population and will address the full spectrum of cognitive brain health and memory disorders.

The hub houses two divisions in the UAB Department of Neurology: the Division of Neuropsychology and the Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. In addition to the two divisions, the Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the UAB Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute are located in the new space.

“We were tasked with a mission to create a new care model that would advance the research and meet the clinical needs of our patients,” said David Geldmacher, M.D., director of the UAB Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. “We realized we did not need more of what we’ve been doing, but rather needed to develop a different system altogether. The new hub is a unique, integrated model that we have yet to see at other institutions.”

Memory disorders are often complex conditions and require a team approach, including neurologists, nurses and nurse practitioners, nurse care managers, pharmacy specialists, and social workers and counselors. The new Brain Aging and Memory Hub will increase collaboration and streamline efforts from prevention to research to clinical care.

“Each member of our team plays a crucial role in fostering research and compassionate care for our patients,” Geldmacher said. “Being able to walk down the hallway, instead of hopping on a call, will eliminate barriers and create a more cohesive and effective environment.”

Ronald Lazar, Ph.D., director of the Division of Neuropsychology and UAB Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute, and his team look forward to advancing brain aging and cognitive decline research and care in the new hub. “Studies show that 40 percent of all dementia cases can be either postponed or prevented entirely,” Lazar said. “There are lifestyle behaviors and risk factor management tools that can mitigate and prevent future memory problems. We want to promote brain health across people’s lifespans, not only once they hit 60.”

In May 2024, the UAB Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) received a $21.4 million award over five years from the National Institutes of Health. This is a significant advance toward addressing the disproportionately high rates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Alabama and the Deep South. Contributing to this disparity, the region is populated with groups disparately impacted by dementia due to factors associated with race, adverse social determinants of health, chronic health conditions, and other issues. The region is also home to the nation’s largest population identifying as Black or African American, who are estimated to be at double the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Realizing the center’s vision of a future in which these disparities in Alzheimer’s disease are eliminated requires a deeper understanding of how this unique amalgamation of factors drives higher rates of dementia. Previous funding from the NIH’s National Institute of Aging has helped the center establish the teams, programs, and infrastructure to pursue this goal, and it has exceeded recruitment goals with a cohort that is nearly 60 percent Black/African American.

With the new funding, the ADRC, led by Erik Roberson, M.D., Ph.D., will build on this initial track record of success by providing coordinated infrastructure that leverages UAB’s strengths to answer questions necessary to reduce Deep South disparities in dementia. It will also continue recruiting a cohort that reflects the unique and diverse population of the Deep South and collecting a broad dataset from participants that informs about potential foundations for Deep South disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), including clinical, social determinants of health, activity/sleep, genetic, and biomarker data. By collecting and sharing biospecimens from participants in a unique Deep South cohort with researchers across the country, the ADRC will help increase diversity in national ADRD initiatives; foster innovative and impactful ADRD research, especially projects addressing Deep South disparities in dementia; attract and train the next generation of ADRD researchers; and increase awareness of ADRD among the public and at UAB.

– Hannah Echols