Getting accepted to and completing medical school is a challenge for any candidate but is even more challenging for people with physical, mental, or learning disabilities who frequently experience bias and discrimination.

Getting accepted to and completing medical school is a challenge for any candidate but is even more challenging for people with physical, mental, or learning disabilities who frequently experience bias and discrimination.

Technical standards (TS) refer specifically to a medical education program’s essential nonacademic requirements. They consist of certain minimum physical and cognitive abilities as well as sufficient mental and emotional stability. These physical, mental, and emotional skills include carrying out conceptual, integrative, and quantitative thought processes; exhibiting appropriate social and behavioral attributes; making observations and assessments; and communicating with others.

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) debuted its TS guidelines in 1979, but technical standards have changed little over the past 40 years, even after the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 expanded schools’ obligations to provide access and accommodations to people with disabilities. Moreover, a 2016 study in Academic Medicine says many TS violate ADA rules because the TS wording is unclear or hard to find on school websites.

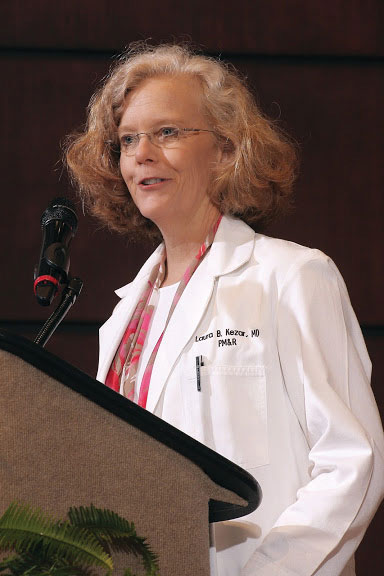

To address the issue, the Association of Academic Physiatrists asked Laura Kezar, M.D., a professor in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and the School of Medicine’s associate dean for students from 2007-2018, to assemble an expert panel to study the technical standards and offer recommendations to update them. Academic Medicine published the panel’s paper this year.

To address the issue, the Association of Academic Physiatrists asked Laura Kezar, M.D., a professor in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and the School of Medicine’s associate dean for students from 2007-2018, to assemble an expert panel to study the technical standards and offer recommendations to update them. Academic Medicine published the panel’s paper this year.

“Schools have been hungry for new guidance because the world has changed so much in the past 30 years,” says Kezar. “The technological revolution we’ve experienced has been as impactful as the Industrial Revolution and empowers many individuals with disabilities, yet we have no new guidance for medical schools and most health professions schools.”

Kezar says some might assume students with disabilities like psychiatric illness, visual impairment, or paralysis can never become physicians. As associate dean for students, Kezar helped students obtain reasonable disabilities accommodations, such as requesting extended time on an exam, gaining access to large-print textbooks, or getting a computer program to read materials aloud.

Helping these students succeed can benefit the medical profession, Kezar says. “Physicians with disabilities bring unique perspectives to the practice of medicine and help create a diverse physician workforce prepared to meet the needs of a wide variety of patients. For students with disabilities, accommodations can level the playing field and provide an opportunity to demonstrate the competencies necessary for the practice of medicine. Updating technical standards is a critical first step in this process.”

The journal article states physicians today are more likely to work in teams that may include physician assistants and nurse practitioners, and more physicians are using technologies like telehealth. As a result, the authors suggest that medical schools keep in mind physicians’ and advanced technologies’ evolving roles in helping schools offer reasonable accommodations for the disabled when updating their TS.

The authors conclude by making eight recommendations and suggesting two functional approaches to TS consistent with the growing trend toward competency-based medical education. The medical community responded positively to the article, Kezar says. Moreover, the panel has shared the report with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the medical school accrediting agency. Physicians from outside the U.S. have also made inquiries regarding the paper’s recommendations, and the AAMC continues to bring attention to the topic of disabilities within the profession.

“We hope they’ll begin to move those standards so they reflect the ADA and the needs and opportunities of today’s world,” says Kezar.

– By Gail Allyn Short; Brit Blalock contributed to this article.