Written by: Matt Windsor

Media contact: Adam Pope

Blood pressure consists of two numbers. Systolic pressure, the force exerted on blood vessels when the heart beats, is the upper number. Diastolic pressure, the force exerted when the heart is at rest, is on the bottom — in more ways than one. Systolic pressure attracts the lion’s share of attention from physicians and patients, says UAB cardiologist Jason Guichard, M.D., Ph.D.

“Physicians are busy people, and like it or not they often focus on a single number,” Guichard said. “Systolic blood pressure is the focus, and diastolic pressure is almost completely ignored.” That is a mistake, he argues. “The majority of your arteries feed your organs during systole. But your coronary arteries are different; they are surrounding the aortic valve, so they get blood only when the aortic valve closes — and that happens in diastole.”

Diastolic pressure has been getting more attention lately, however, thanks in part to an influential paper in Hypertension, written in 2011 by Guichard and Ali Ahmed, M.D., then a professor of medicine in UAB’s Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care and now the associate chief of staff for Health and Aging at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C. (Ahmed remains an adjunct faculty member at UAB.)

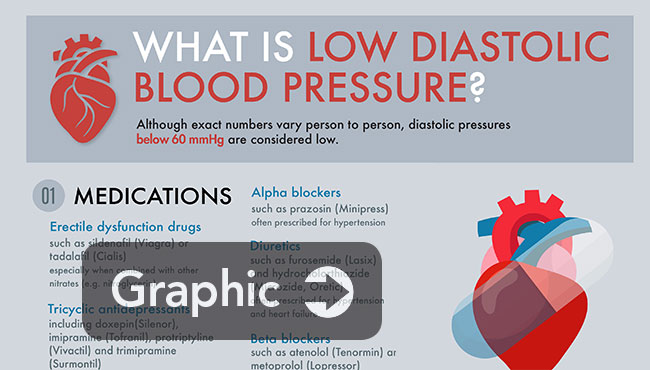

INFOGRAPHIC: See our quick guide to causes, and treatments, for low diastolic blood pressure.

INFOGRAPHIC: See our quick guide to causes, and treatments, for low diastolic blood pressure.

That paper coined a new term, “isolated diastolic hypotension,” which refers to a low diastolic blood pressure (less than 60 mm Hg) and a normal systolic pressure (above 100 mm Hg). Older adults who fit those conditions are at increased risk for developing new-onset heart failure, the researchers found.

“High blood pressure is a problem, but low blood pressure is also a problem,” Guichard said. That realization helped drive a 2014 decision by the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) to relax target blood pressure guidelines for those over 60 years old. [Read Guichard's take on "ideal blood pressure" and the new guidelines in this blog post.]

“Years ago and until recently, doctors were treating blood pressure so aggressively that many patients couldn’t even stand up without getting dizzy,” Guichard said. “We want to empower patients to know that you don’t have to drop those numbers all the way down to nothing, to the point where you can’t play with your grandkids or play golf or take a simple walk around the block because your blood pressure is so low. I think it’s important to raise awareness in this area, especially for older people.”

Jason GuichardAhmed and Guichard are continuing to explore the mechanisms behind low diastolic pressure in more detail. Several new papers are pending, Guichard says. In the meantime, he sat down with The Mix to explain the dangers associated with low blood pressure.

Jason GuichardAhmed and Guichard are continuing to explore the mechanisms behind low diastolic pressure in more detail. Several new papers are pending, Guichard says. In the meantime, he sat down with The Mix to explain the dangers associated with low blood pressure.

Most people are trying to lower their blood pressure. What would you define as “too low,” and why is that a problem?

A diastolic blood pressure of somewhere between 90 and 60 is good in older folks. Once you start getting below 60, that makes people feel uncomfortable. A lot of older folks with low diastolic pressures get tired or dizzy and have frequent falls. Obviously, none of that is good news for people who are older, who potentially have brittle bones and other issues.

Your coronary arteries are fed during the diastolic phase. If you have a low diastolic pressure, it means you have a low coronary artery pressure, and that means your heart is going to lack blood and oxygen. That is what we call ischemia, and that kind of chronic, low-level ischemia may weaken the heart over time and potentially lead to heart failure.

What could cause a person to have low diastolic blood pressure?

Medications are a big one. There are some medicines that are culprits for lowering your diastolic blood pressure more than your systolic — specifically, a class of medications called alpha blockers, or central acting anti-hypertensive agents.

Another reason is age. As you get older, your vessels become a little more stiff, and that tends to raise your systolic pressure and lower your diastolic pressure.

It’s hard to reverse the aging process; but one potential therapy is to find ways to allow your vessels to retain their elasticity — or, if they’ve lost it, maybe ways to gain that back.

The best current treatment is to lower dietary salt intake, which has been shown to be very closely linked with the elasticity of your vessels. The more salt you eat, the less elastic your vessels will be. Most peoples' salt intake is too high. Salt intake is a highly debated topic in medicine, but most believe that dietary salt intake of greater than 4 grams per day is too high, and less than 1.5 grams per day is too low. This depends on a person's age and underlying medical problems, but this range is a good rule of thumb. There is some data that the ideal salt intake for healthy people is around 3.6 grams per day, but again this is highly debated.

UAB’s hypertension group, led by Dr. Suzanne Oparil and Dr. David Calhoun, has detailed much of the basic science showing the effect of salt at a molecular level in the blood vessels. On the inside, your blood vessels are lined with a thin monolayer of endothelial cells. In an experimental setting, adding salt to these cells causes changes almost immediately. They become less reactive — that means they stiffen up — and lose their elasticity, which is what you actually see clinically.

Additionally, the stiffening of the vessels happens very soon after you take on a salt load during eating, which is very interesting.

Beyond changes in medications, what can people do to raise their diastolic pressure if it’s too low?

Lifestyle changes like diet and exercise can have immediate effects. Your inside changes much quicker than the mirror shows you. On the inside, you’re getting much more healthy by eating better, getting exercise, controlling your weight and not smoking.

Everyone thinks, “I’m going to have to do this for six months or a year before I see any changes.” That’s not true. The body is very dynamic. Within a few weeks, you can see the benefits of lifestyle change. In fact, with dietary changes in salt intake, you can see a difference in a day or two.

If someone does have low diastolic pressure, what should they — and their doctors — look for?

If they aren’t on medications that we could adjust, the important thing is close monitoring; maybe seeing a patient more frequently in clinic and monitoring them closely for cardiovascular disease or heart failure symptoms.

Your original study in Hypertension got a lot of attention. What are you working on now?

We’re finalizing some papers that address two big criticisms of that study. The first criticism was that we were looking strictly, as the name suggests, at isolated diastolic hypotension. We didn’t really care at the time what the systolic pressure was doing; but a high systolic pressure is a risk for heart failure, among other things. When we looked at the patients in our study, their systolic blood pressures were all relatively normal, and we adjusted for patients with a history of hypertension.

So we actually went back and redid the analysis, completely excluding people with hypertension. And the results still remained true. In fact, the association was even stronger.

The other criticism involved something called pulse pressure. That’s the difference between your systolic and diastolic blood pressure. And multiple studies have shown that a widened pulse pressure is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Some fellow researchers said, “Really, all you’re looking at is just a wider pulse pressure. This isn’t necessarily novel — that’s been shown before.”

So we’ve actually looked at pulse pressure differences in all these patients and broken them down by differences in pulse pressure. And even when we adjusted for pulse pressure, the conclusion about the low diastolic pressure still rang true.

We actually looked at three different groups of pulse pressure — normal, wide and really wide. And it was true throughout. Low diastolic blood pressure increased one’s risk for heart failure.

You also have an interest in diastolic heart failure. What is that?

There are two different types of heart failure: one where the pumping function of the heart is abnormal — that is known as systolic heart failure — and one where the relaxation function is abnormal — that is known as diastolic heart failure. We have lots of medicines for, and experience treating, systolic heart failure, which is also called “heart failure with reduced ejection fraction” — everything from beta blockers, ACE inhibitors and ARBs to mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and statins.

Diastolic heart failure, or “heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” has no approved pharmacologic therapies to date. It was widely overlooked, to be honest, until about 10-15 years ago, when physicians realized that these poor patients were having terrible heart-failure symptoms but none of the classic objective measures of heart failure. In most cases, you can’t even tell the difference between a person with systolic and diastolic heart failure based on their symptoms. On the inside, however, their heart is pumping just fine; the problem is their heart is stiff — it doesn’t relax as well as it should. That stiffness leads fluid to back up into the lungs and extremities and causes a lot of the symptoms that you have with systolic heart failure, but the pumping function of the heart is normal.

Now that there is an awareness of diastolic heart failure, we’re realizing that it is a very common problem. It looks like there are as many people with diastolic heart failure as with systolic heart failure. As a matter of fact, there may even be more people with diastolic heart failure.

It has become a heavily studied form of heart failure right now. Everyone is clamoring to get a medicine to help these patients, because it turns out to be very prevalent, and a lot of times they have the same morbidity and mortality as people with systolic heart failure.