A systematic review from the University of Alabama at Birmingham shows that routinely opting for a repeat cesarean delivery over first attempting a vaginal delivery may result in excess morbidity and cost from a population perspective for women with a prior low transverse incision cesarean delivery who are likely to have a successful vaginal delivery.

A systematic review from the University of Alabama at Birmingham shows that routinely opting for a repeat cesarean delivery over first attempting a vaginal delivery may result in excess morbidity and cost from a population perspective for women with a prior low transverse incision cesarean delivery who are likely to have a successful vaginal delivery.

Healthy People 2020, a national public health campaign, has set a goal of reducing repeat cesarean births by 10 percent by 2020 among low-risk women to reduce morbidity in women, as well as health care costs.

Cesarean deliveries account for 32 percent of nearly 4 million births annually in the United States. According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, most women with one previous cesarean delivery are candidates for a trial of labor after cesarean, or TOLAC, the attempt to have a vaginal birth after cesarean delivery.

Due to a variety of factors including patient preferences, provider fears of litigation, hospital culture and the medical reason for the primary cesarean delivery, more than 90 percent of women go on to have a repeat cesarean delivery.

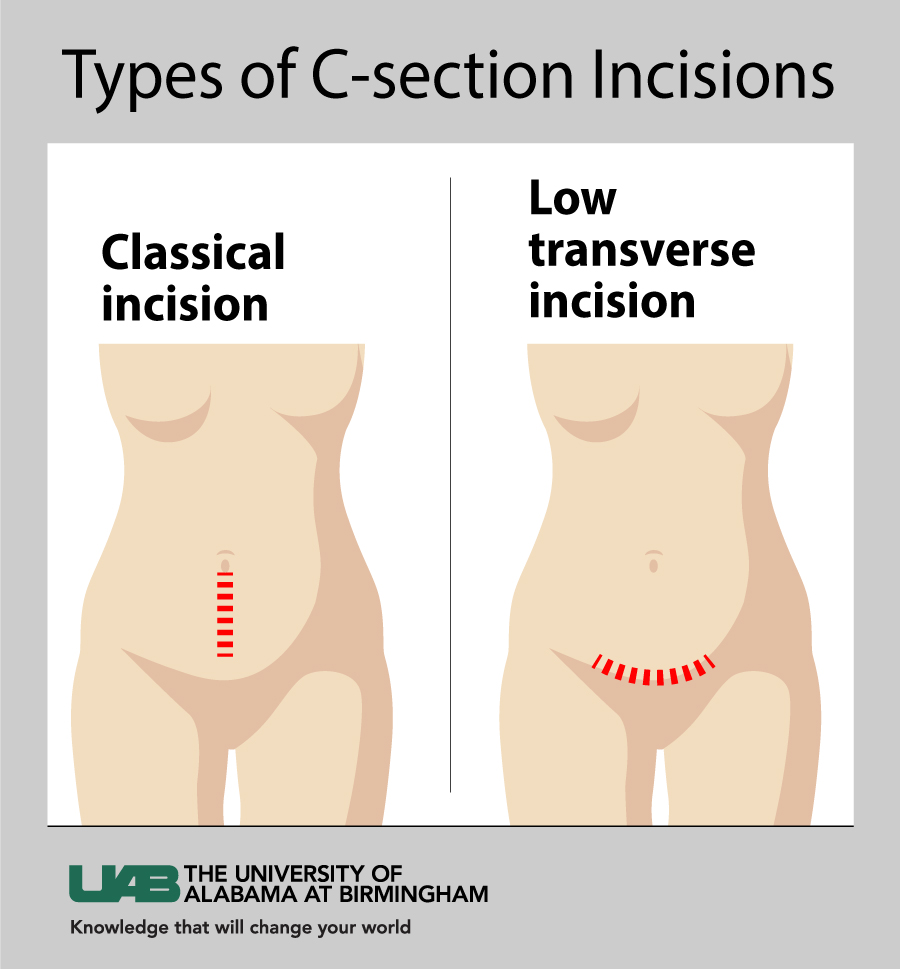

“The conventional wisdom is ‘once a cesarean, always a cesarean,’” said Anna Joy Rogers, M.D., Dr.P.H. candidate in the UAB School of Public Health Department of Health Care Organization and Policy. “Older C-section incision techniques posed a higher risk of uterine rupture during future attempts at a vaginal delivery, so patients and physicians often felt more comfortable with a planned C-section. Our study found that, when we look at the big picture, routinely choosing a C-section may actually come at a higher cost and result in more women having poorer outcomes. This is especially true for women who plan to have several children after the primary C-section.”

The systematic review published in Value in Health looked at seven studies comparing a TOLAC to an elective repeat cesarean delivery, or ERCD, with information on the relative costs and health effects of the alternative delivery options. The authors compared the studies on a wide range of metrics, including study quality.

Modeling under their best assumptions, four of the seven studies reviewed showed that ERCD was less effective and more costly; one study calculated that ERCD was more effective and less costly. Two studies found that ERCD was slightly more effective for an additional cost, but concluded that society may not be willing to pay the high price for the additional benefit that routinely conducting ERCDs may offer.

Results highlight the importance of making sure that women with certain characteristics that may hamper their ability to deliver vaginally, such as a history of failing to progress in labor, or put them at risk of a uterine rupture, such as obesity or a short inter-pregnancy interval, are carefully screened for their TOLAC eligibility.

While uterine ruptures are a rare but serious complication of a TOLAC, a cesarean delivery is a major surgical procedure associated with its own set of risks.

“Patients should receive comprehensive counseling in order to appropriately weigh the pros and cons of each mode of delivery,” said Lorie Harper, M.D., associate professor in the UAB School of Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. “Ultimately, physicians should guide their patients to make the decision in light of their short-term labor preferences, as well as their long-term family and health goals.”

The results of this cost-effectiveness study are in line with the clinical consensus that most low-risk women are candidates for a TOLAC.