Media contact: Savannah Koplon

Brooke Becker

Brooke Becker

Photography: Bruce SoutherlandThe Pew Research Center reported in 2020 that just over a quarter of Americans — 26 percent — get their news from YouTube.

Americans are as likely to turn “to independent channels as they are to established news organization channels,” the center noted, and videos from independent news producers are “more likely to cover subjects negatively [and] discuss conspiracy theories.”

How can consumers assess the media they consume and avoid mistaking mis- or disinformation for the real thing? Brooke Becker, media literacy librarian from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Libraries, recommends brushing up on digital and media literacy — the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication. Being media literate is a crucial life skill in today’s world, Becker explains, both in understanding digital messages in the workplace and evaluating media consumed on personal time.

“Media literacy empowers us to be critical thinkers with the necessary skills to make better decisions in all aspects of our lives,” Becker said. “The media we consume influences choices we make at work, at home and throughout our society.”

Timely with an influx of information surrounding world events and news, Becker shares expert tips on how to be a shrewd media consumer in the 21st century — through considering the role of access to information, analyzing media for factors such as credibility and context, and participating in self-reflective interpretation of available messages.

Learn more about media literacy in this research guide from UAB Libraries.

Tip No. 1: Consider what and how you access news

A core principle in learning to parse the facts from mis- and disinformation is considering the information channels to which one has access, Becker explains. Access is defined as how, when, where and how often people have access to the tools, technology and digital skills necessary to thrive, according to the National Association for Media Literacy Education.

How consumers access information can determine what information they receive. If consumers rely on outlets such as social media platforms or other curated media to provide news and information, NAMLE cautions, it is likely they might only see the content provided by algorithms or individuals with ill intent.

“There’s so much information out there now that it’s easy to think everyone knows what you know, has access to the same fact-checking sites or the same apps, but it’s not true,” Becker said. “Age, income, language, geography, etc. all impact what we know, the information to which we have access and who we trust to provide that information.”

It’s important to remember what information is most easily accessible, Becker says. Information behind paywalls, such as that from traditional scholarly, or more well-researched, sources, is not easily (or freely) accessed by people from under-resourced communities, which often encompass marginalized and minority groups.

“Information deserts can have a profound impact on society at large,” Becker said. “This was never more readily apparent than during the switch to remote learning and work during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

Graphic by: Haley HerfurthTip No. 2: Learn to analyze the media you consume

According to NAMLE, analyzing media content means asking questions about a piece of media to identify authorship, credibility, purpose, technique, context and economics. Understanding more about who created a piece of information — their knowledge base, intent for creation and biases, specifically — can help consumers determine the accuracy of the message, Becker explains.

Key questions to ask (from Center for Media Literacy):

- Authorship: Who created and/or paid for it?

- Format: What techniques are used to attract my attention and why?

- Audience: How might someone else understand this message differently than I do?

- Content: What lifestyles, values and points of view are represented in, or omitted from, this message?

- Purpose: Why is this message being sent? Are they selling something or trying to influence me for their own benefit?

Tip No. 3: Work to analyze and self-reflect on media messaging

In media literacy, NAMLE notes, evaluating media content involves drawing one’s own meaning, judgment and conclusions about media messages based on the information gathered during media access, thoughtful analysis and self-reflective interpretation. Becker adds that asking thoughtful questions about media’s creative, potentially manipulative, or propaganda-like qualities can help consumers investigate the deeper effects of media messages.

“Taking time to think about what you are hearing, reading or seeing is the best way to combat misinformation,” Becker said.

Key questions to ask (from NAMLE):

- How credible is this and how do I know?

- Is this fact, opinion or something else?

- Can I trust this source to tell me the truth about this topic?

- Who might benefit from this message? Who might be harmed by it?

- How does this make me feel and how do my emotions influence my interpretation of this?

- Is this message good for me or people like me?

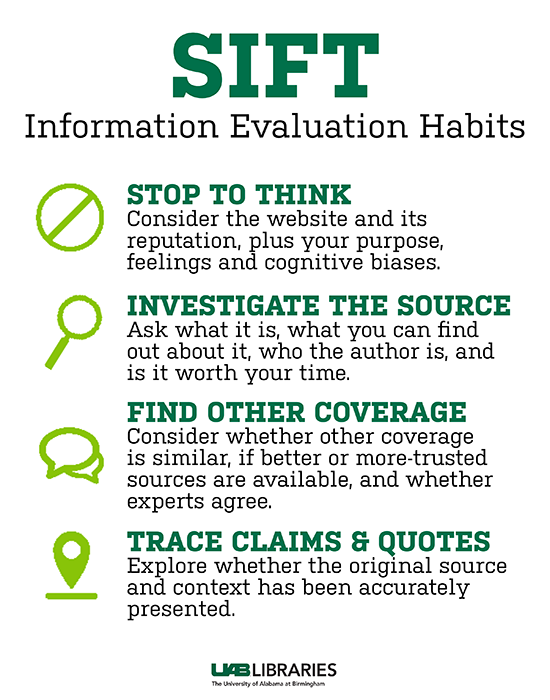

Bonus tip: Remember the SIFT Method

Using the SIFT Method is another way to ensure you can differentiate between the good, the bad and the ugly when evaluating media sources, Becker explains. Developed by Mike Caufield at Washington State University, Vancouver, the method encourages consumers to Stop, Investigate, Find and Trace information when reviewing for mis- or disinformation.

Learn more about media literacy in this research guide from UAB Libraries.