Illustration by: Jody PotterCrying makes us human. It is a testament to our ability to feel, empathize and cope.

Illustration by: Jody PotterCrying makes us human. It is a testament to our ability to feel, empathize and cope.

While crying is usually associated with distressing experiences, positive yet overwhelming experiences such as receiving an award, a marriage proposal or watching a touching movie can cause people to tear up as well. People may cry because they are overstimulated. Many reasons can cause this type of crying, such as having a difficult personal or professional conversation, not knowing what to say because one is overwhelmed, or because an upsetting memory is triggered.

The reason is that crying usually happens when psychological demands exceed some sensory-affective threshold, according to the University of Alabama at Birmingham psychologist Christina Pierpaoli Parker, Ph.D.

Crying: a combination of sensitivity, meaning and vulnerability

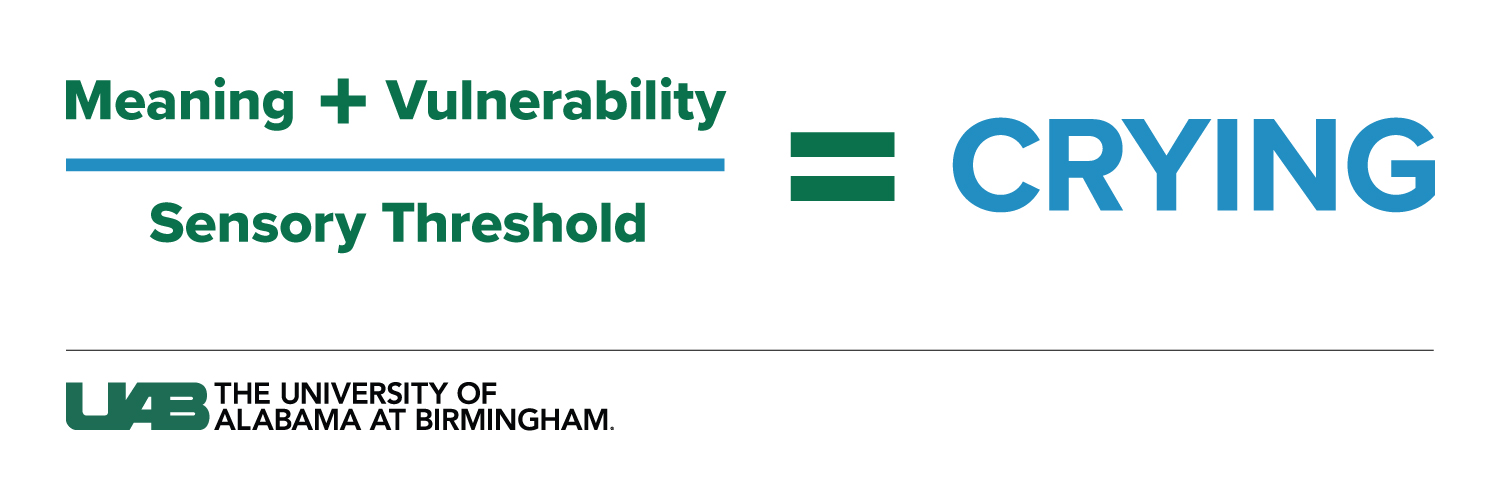

Parker, assistant professor in the UAB Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, conceptualizes crying as sensitivity plus meaning divided by sensory threshold.

“When psychological demands exceed our resources, we become vulnerable to crying,” Parker said.

Parker says people vary in their proneness to crying because of their unique predispositions, sensitives, vulnerabilities and values — much like having a different emotional volume setting.

“When we don’t have enough reserve in our psychological savings account, and the things we care about get activated or threatened, we can overdraft, or cry,” Parker said. “Why people cry — from overstimulation, stress or joy — depends on the resources they have and what they define as meaningful.”

The science behind crying

The body and brain are always trying to achieve and maintain homeostasis. When a person’s sensory threshold is crossed, tears release pleasure hormones, oxytocin and endorphins, to restore stability — emotional equilibrium.

“Tears relieve psychological pressure accumulated within our sympathetic nervous system to restore homeostasis,” Parker said. “This release of pressure eases both physical and emotional pain and tension.”

Graphic by Jody PotterAccording to Parker, tears help us encode and remember personally meaningful information, helping us learn about ourselves, which positively impacts our mental health.

Graphic by Jody PotterAccording to Parker, tears help us encode and remember personally meaningful information, helping us learn about ourselves, which positively impacts our mental health.

However, if someone experiences excessive tearfulness that impairs their daily functioning and causes distress, it may constitute a medical and/or clinical concern, such as major depressive disorder, or dry eye. If that happens, Parker recommends connecting with your physician.

Beyond gender: the universality of tears

Tears are a source of interpersonal and intrapersonal information sharing and have nothing to do with sex or gender, Parker says.

Crying usually tells us what we care about and what we need, especially when we are unable to articulate those needs and values verbally.

Infants, toddlers and children tend to cry more often than adults because it is typically their only and most reliable way of communicating. They are pre-verbal and have not developed the cognitive software for language like adults.

“Crying has nothing to do with sex or gender; it has to do with humanity,” Parker said. “It is only human to weep emotional tears.”

“We’re born with all the emotions but few of the skills to regulate them,” Parker said. “Over time, both men and women can develop and learn emotion regulation skills to develop an emotional brake system.”

While people develop a regulatory system for their tears, men and women tend to internalize different scripts about expressing emotion based on social, cultural and other contextual norms, which likely explains the observed discrepancy between tears in men and women.

Biopsychosocial differences across people — in personality, predisposition, experience, culture, family, gender scripts and norms — interact in complex ways to produce variations in crying behavior.

Honoring emotions

Those experiencing the urge to cry should know that it is because the body just shifted to limbic mode that guides survival behaviors. Parker recommends honoring this urge because “the more you tell yourself not to, the more likely you are to cry.”

While the comforting mechanism should be context-based, usually validation, empathy and reflection are the best ways to console a crying person, Parker says.

“When someone is crying because of emotional distress or because they are overwhelmed, consider saying, ‘I know this is emotional for you, I believe you, and I’m here. We’re going to get through it together,’” Parker said.