A continuous glucose monitor consists of a small patch on the upper arm or abdomen that communicates with a patient's smartphone or dedicated device to give an instant update on blood glucose levels throughout the day and night.Late last year, UAB photographer Steve Wood began to wonder if middle age was catching up with him. “I was tired all the time — I just had no energy,” he said. He was also losing weight without dieting or exercise, and was making an unusual number of trips to the bathroom.

A continuous glucose monitor consists of a small patch on the upper arm or abdomen that communicates with a patient's smartphone or dedicated device to give an instant update on blood glucose levels throughout the day and night.Late last year, UAB photographer Steve Wood began to wonder if middle age was catching up with him. “I was tired all the time — I just had no energy,” he said. He was also losing weight without dieting or exercise, and was making an unusual number of trips to the bathroom.

Those last symptoms sounded familiar. Both of his sons have been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, so Wood knows all about insulin injections, test strips and glucose meters, and how changing blood sugar levels can affect the body. But Type 1 is usually diagnosed during childhood. Wood went to see his sons’ doctor, Fernando Ovalle, M.D., director of the UAB Multidisciplinary Comprehensive Diabetes Clinic, thinking he might have Type 2 diabetes. He left with a surprising diagnosis — it was Type 1 — and a little patch on his upper arm that syncs to his smartphone, giving him an instant update on his blood sugar levels. It is called a continuous glucose monitor.

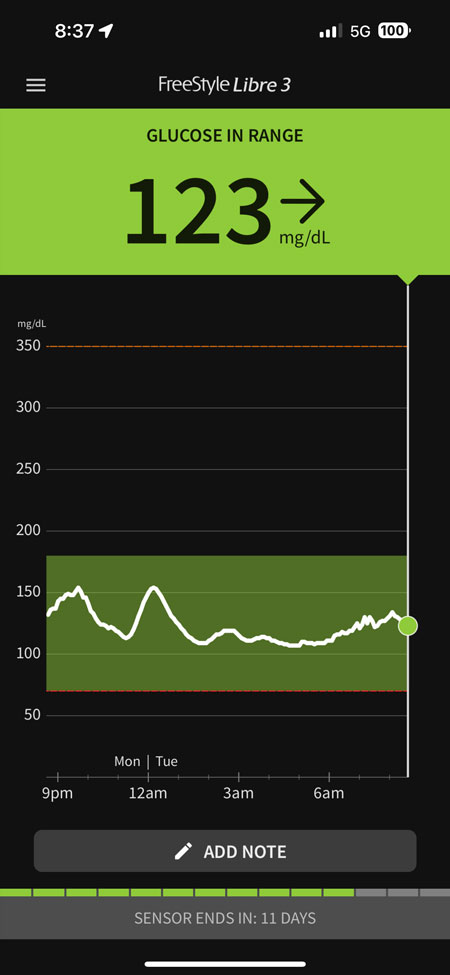

“I probably check it 20 times a day,” Wood said. “I am still trying to regulate my insulin — how much did I give myself before that meal, how did it work? Was it too much, too little? It depends on the meal: Pizza does this, pasta does that. I can look at my phone and see the trends, quickly. If you get a down arrow, your blood sugar is starting to drop. If there are two arrows, it is dropping really fast. You can head it off before it gets bad.”

“We are just wired differently”

Like Wood, more than 7 million Americans have diabetes severe enough to require daily insulin injections and close monitoring of their blood glucose levels. But keeping those glucose levels in the proper range is maddeningly personal.

“Two brothers can eat the same thing and in one glucose will go higher,” said Ovalle, professor and medical director of Diabetes and Glycemic Control Programs for the UAB Heersink School of Medicine and director of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism. “Genetically we are just wired differently, and we respond in different ways to food, exercise and stress.”

Continuous glucose monitors have become a “game-changer” in diabetes management, said Fernando Ovalle, M.D., director of UAB’s Multidisciplinary Comprehensive Diabetes Clinic.In a recent episode of the UAB MedCast podcast, Ovalle explained that continuous glucose monitors have become a game-changer in diabetes management. The devices allow people with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes to get a constant readout on their blood sugar levels every few minutes, day and night, instead of the moment-in-time snapshot of a fingerstick. Small wires pushed just under the skin (usually on the upper arm or abdomen) do the measurement. They send results wirelessly to the user’s smartphone or a separate small device. An onscreen chart shows whether glucose is rising or falling.

Continuous glucose monitors have become a “game-changer” in diabetes management, said Fernando Ovalle, M.D., director of UAB’s Multidisciplinary Comprehensive Diabetes Clinic.In a recent episode of the UAB MedCast podcast, Ovalle explained that continuous glucose monitors have become a game-changer in diabetes management. The devices allow people with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes to get a constant readout on their blood sugar levels every few minutes, day and night, instead of the moment-in-time snapshot of a fingerstick. Small wires pushed just under the skin (usually on the upper arm or abdomen) do the measurement. They send results wirelessly to the user’s smartphone or a separate small device. An onscreen chart shows whether glucose is rising or falling.

“Continuous glucose monitoring has really transformed the way we manage patients,” said Ovalle, who is also associate director of the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center. “It makes everything more clear and less frustrating.”

Wood agreed: “It is just so much easier — and it also helps you see how your blood sugar is trending more than a single finger-prick can tell you.” Continuous glucose monitors can also be useful for those helping care for someone with diabetes. Wood’s younger son uses a continuous glucose monitor as well, and because the devices operate using Bluetooth, Wood and his wife are able to check on their son’s blood sugar levels while he is on the ice during hockey games. “That is very cool that we are able to do that,” he said.

“It’s an eye-opener for people to see what happens to their glucose when they eat this food versus that one, what happens when they exercise or don’t, what happens when they are stressed or not,” Ovalle said. “Everyone is a little different, and people learn to figure it out for themselves.”

Changing behavior

Seeing the data is one thing. But in Ovalle’s experience, patients with continuous glucose monitors act on that information. “It’s just such a useful and impactful behavior modification tool,” Ovalle said. Today, about half of the patients with diabetes that Ovalle sees in his clinic are using continuous glucose monitors. “And if it were up to me, maybe 95 percent would be using them,” he said. “I feel that anyone on insulin should have one, whether they are Type 1 or Type 2.”

Continuous glucose monitors first came on the market in the early 2000s; with time, they have become more precise and easier to use. Industry data estimates there are approximately 2.4 million users of continuous glucose monitors in the United States currently and millions more worldwide. One firm estimated that more than 50 percent of Americans with Type 2 diabetes will be using the devices in three years. (Of the 37.3 million Americans with diabetes in 2019, nearly 1.9 million had Type 1 diabetes; the rest had Type 2 diabetes.)

Patients like to see data, Ovalle said: “If you give them a goal — keep your blood sugar within these lines — it’s just like giving them a little game, and people respond to that.”Patients like to see data, even if they do not know it and even if they are not very tech-savvy, Ovalle says. “If you give them a goal — keep your blood sugar within these lines — it’s just like giving them a little game, and people respond to that. For some people, it’s because they are competitive; for some people, it’s because they get concerned; and for some people, it’s because they needed some guidance, and they just didn’t know whether what they were doing was correct or not. They didn’t know what was making things worse and making them better. Giving them that information, by itself, makes people do better.”

Patients like to see data, Ovalle said: “If you give them a goal — keep your blood sugar within these lines — it’s just like giving them a little game, and people respond to that.”Patients like to see data, even if they do not know it and even if they are not very tech-savvy, Ovalle says. “If you give them a goal — keep your blood sugar within these lines — it’s just like giving them a little game, and people respond to that. For some people, it’s because they are competitive; for some people, it’s because they get concerned; and for some people, it’s because they needed some guidance, and they just didn’t know whether what they were doing was correct or not. They didn’t know what was making things worse and making them better. Giving them that information, by itself, makes people do better.”

Research suggests that, “if you put somebody in a continuous glucose monitor and do nothing else, their A1C” — a blood test measuring glucose levels — “improves by about 1 percent,” Ovalle said. “We see that all the time. Some people do even better than that.” For most adults with diabetes, the A1C target is 7 percent. A 1 percentage point improvement is significant, Ovalle points out. “These are people who are already close to their blood glucose target” because they are being treated. “Going from 12 percent to 10 percent is easy; just drink water,” Ovalle said. “But the closer you get to that 7 percent target, the harder it is. You tell people, ‘Wear this and try to keep it in the lines’ and they figure it out — without a drug or the further cost of another medication and side effects and visits.”

“Most people love these things”

That is not to say that every patient is eager to give continuous glucose monitoring a try. “At first, I find that most people are a little skeptical,” Ovalle said. “They don’t want to spend more money, have another copay, and they may be afraid that it is going to hurt. But I am so convinced about these things that, even though I don’t like to push, I do push a little bit with continuous glucose monitoring. I tell patients, ‘You are probably going to change your mind. Most people love these things.’ I get no benefit from their using it, but I see the usefulness. I have seen it in my own life.”

In his own experience, the individual data can be fascinating, Ovalle says. “I like to see what happens when I eat more, eat faster, eat slower, when I change the order. If I eat a meal with rice and meat, I get different results if I eat the rice first and then the meat or the meat and then the rice. We say, ‘Make sure you eat the fat first, then the carbs.’ You can tell people that and they don’t get it. But when you see the glucose going up and down and how it makes you feel, you understand, ‘That’s why I feel so bad after this. No wonder!’ And you see that you can manage your metabolism without having to make major changes.”

People who are on insulin will probably need to use a continuous glucose monitoring device on an ongoing basis, Ovalle explains, but others may benefit simply from using the device for a limited time. That way, they can learn more about their own body’s reaction to food, exercise, stress and other factors. “Today I put one on a doctor who is not on insulin,” Ovalle said. “He needs to lose weight, and this is a great tool to help. He knows what carbs are, what is a good diet and what is a bad diet. But it’s much different when your body tells you. I said, ‘After a few weeks, you won’t need it. But learn from it, and practice what you learn.’”