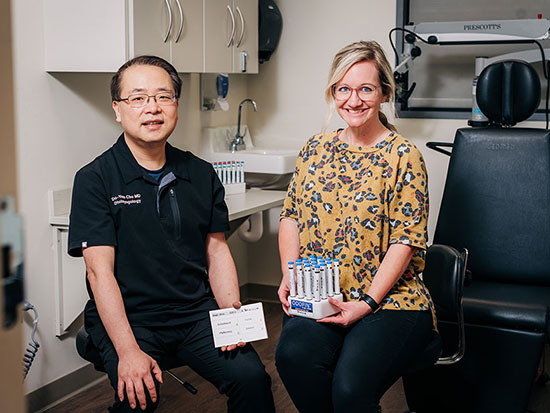

Do-Yeon Cho, M.D., and Carly Bramel, P.A., see patients at the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic. Treatments — starting with olfactory training, also known as smell training — can be very effective at helping patients regains their sense of smell after COVID, Cho says. And UAB research shows that smell training can boost cognition, too.

Do-Yeon Cho, M.D., and Carly Bramel, P.A., see patients at the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic. Treatments — starting with olfactory training, also known as smell training — can be very effective at helping patients regains their sense of smell after COVID, Cho says. And UAB research shows that smell training can boost cognition, too.

ANDREA MABRY | University RelationsIn January 2023, UAB Medicine launched the Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic, thought to be the first specialized clinic in Alabama for patients with olfactory dysfunction. The clinic expands on earlier efforts that were launched in 2020 after UAB specialists saw a significant number of patients who were suffering from post-infectious olfactory disorder after COVID.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, at least 500,000 Alabamians have experienced extended smell and taste loss, says Do-Yeon Cho, M.D., director of the Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic and an associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology in the UAB Heersink School of Medicine. The clinic has seen a high volume of patients since opening, with appointments booked far in advance.

We asked Cho to take a brief time out from his busy schedule to share insights on what causes smell loss, tips on retraining the nose and cutting-edge research from his clinic.

1. Smell loss is actually fairly common, but COVID brought it into the open.

“You don’t appreciate smell until you lose it,” Cho said. He knows. In December 2022, he lost his sense of smell for a few weeks after a COVID infection, and three months later the odor of beef, chicken and cooking oil is still off-putting. “I used to love French fries,” he said. “Now, I order from the vegetarian menu, and I’m not vegetarian.”

Olfactory dysfunction, which includes smell loss and an altered sense of smell, affected 5 percent to 15 percent of the population pre-COVID, according to a review published in 2022. Common causes are:

Age

Nearly 50 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 80 have experienced an impaired sense of smell, the 2022 paper noted. Related to this is the fact that smell loss is an early sign of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other neurological diseases.

Allergies

Chronic rhinosinusitis — inflammation of the nose due to allergies — is perhaps even more likely to cause smell loss than aging.

Head trauma

A blow to the head is another cause — particularly a blow to the nose, which can damage the relatively unprotected olfactory nerve on its route to the brain.

Infections

Post-infectious olfactory dysfunction, including from the common cold and influenza, is another common cause of olfactory dysfunction; it tends to resolve over a year or more.

COVID: That same pattern seems to be happening with SARS-CoV-2; but smell loss or smell changes were far more likely to be reported after COVID than with cold or flu, especially the original SARS-CoV-2 strain. (Subsequent COVID variants still cause olfactory dysfunction, although at lower rates.)

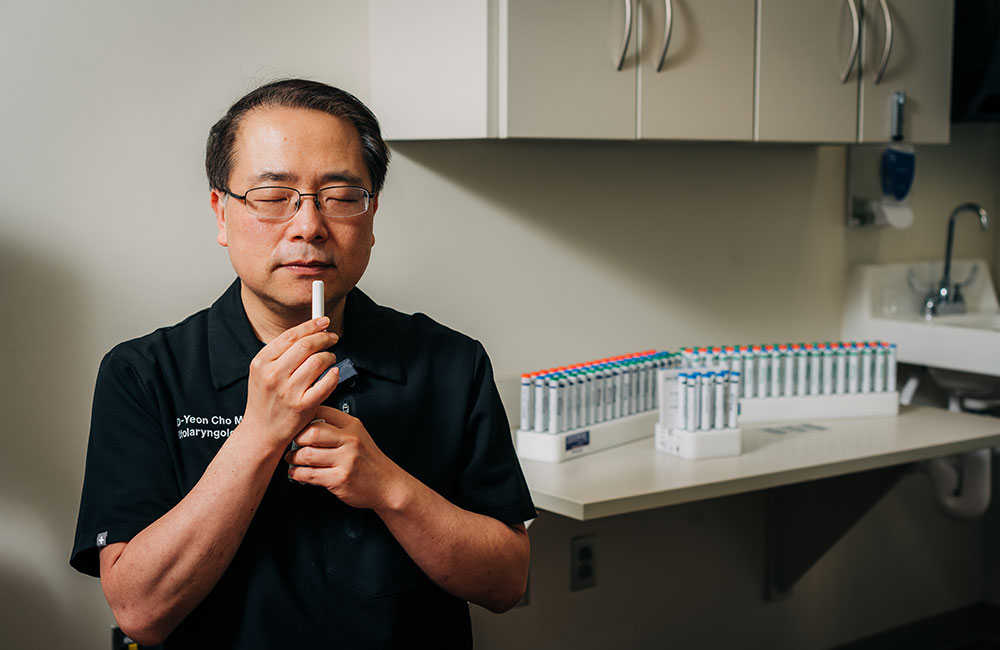

Threshold discrimination identification testing is the gold standard for testing smell loss and smell dysfunction. Patients smell a series of odors of various types and concentrations from what look like felt-tip pens. The testing offers an objective score measuring the patient’s ability to distinguish smells from one another and to distinguish the intensity of smells.

Threshold discrimination identification testing is the gold standard for testing smell loss and smell dysfunction. Patients smell a series of odors of various types and concentrations from what look like felt-tip pens. The testing offers an objective score measuring the patient’s ability to distinguish smells from one another and to distinguish the intensity of smells.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

2. Proper examination and testing is the best way to match the right treatment to the patient.

COVID and the media attention around COVID smell loss have brought more people to clinics such as Cho’s; but that does not mean every patient’s smell loss can be attributed to COVID, even if a COVID infection was the first time they noticed it.

Examination

“I examine patients every time they come in,” Cho said. “A lot of patients did indeed lose their sense of smell from COVID; but some have foreign bodies in their noses, and others have large nasal polyps.”

These polyps are often the result of allergies. “We have a lot of pollen in Alabama,” Cho said. “Inflammation or nasal polyps can both block the nose and alter the sense of smell.” Treatment in this case is a steroid rinse.

Other symptoms

Cho also asks patients about other symptoms. “If they have headache or another neurogenic issue,” he will often recommend an MRI or CT imaging scan of the brain and, if warranted, a referral to a neurologist. Cho will also talk with patients or caregivers about their family history of Parkinson’s disease or early-onset dementia. “Smell loss can be the first symptom of neurodegenerative disease,” Cho said. How does he distinguish it from COVID-related smell loss? Timing is important. If the cause is related to neurodegenerative disease, “smell loss is not abrupt,” Cho said. “Patients will often say they have noticed it for a few years.”

Taste

Another thing Cho asks about is taste. “Smell loss is related to taste loss,” he said. “There are smell nerves deep in the back of the nose. When you are chewing, the flavor goes through the back of the mouth and is sensed at the back of the nose.” (This is called retronasal odor identification.) When patients still can taste food, “that is a good sign,” Cho said. “That means there are still nerves working somewhere, likely in the very back of the nose.”

Threshold discrimination identification testing

After a physical exam of the nose and a discussion of symptoms and timing, Cho uses threshold discrimination identification testing to evaluate the severity of smell loss or dysfunction.

“We are probably the only location doing threshold discrimination identification testing, or TDI testing, in Alabama,” Cho said. This is the current gold standard for testing, he notes. Patients smell a series of odors from what look like felt-tip pens. The odors are at various concentrations — the testing gives an objective score measuring the patient’s ability to distinguish smells from one another and to distinguish the intensity of smells.

“Testing is very important, because everybody is very different related to smell,” Cho said. “Some people are super smellers. They usually smell everything, and even if they only have a slight bit of smell loss, they feel they can’t smell. I saw a patient recently and her test results were almost normal. She said, ‘But Dr. Cho, I can’t smell anything!’”

Not all patients have lost the ability to smell. In fact, a significant minority experience what is known as parosmia — a distorted sense of smell. For most patients with parosmia, normal smells are perceived as something foul and unpleasant. (For more on treating parosmia, see below.)

“That is why testing gives you guidance to counsel patients,” Cho said.

Smell training generally uses four different types of smells: sweet (fruit), flower, resinous and spicy. Because of the widespread smell loss associated with COVID, smell training kits are widely available in stores and online. "You can absolutely use essential oils," Cho said.

Smell training generally uses four different types of smells: sweet (fruit), flower, resinous and spicy. Because of the widespread smell loss associated with COVID, smell training kits are widely available in stores and online. "You can absolutely use essential oils," Cho said.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

3. In most cases, olfactory training — smell training — is beneficial. Here is how smell training works.

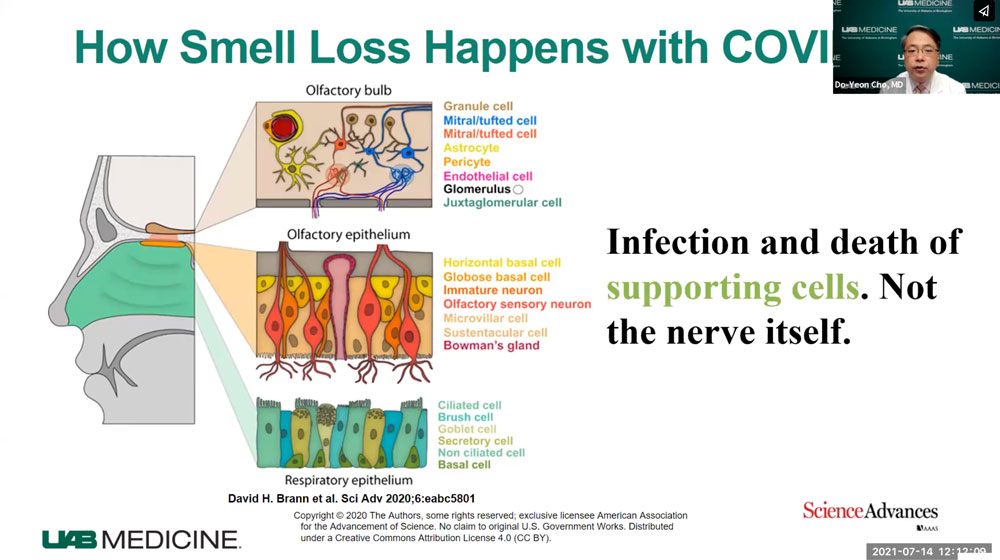

Researchers continue to debate the underlying reason for smell loss or dysfunction: Is it due to the deaths of the olfactory neurons that sense odors within the nose, or a failure within the brain itself, in the regions that consolidate and make sense of the signals they receive from the sensing neurons?

Either way, smell training is helpful for many patients, Cho says. “Thirty to 40 percent of patients see significant improvement” after smell training, he explained. The training helps rebuild the connections between the nose and the brain and helps participants relearn to accurately identify types of smells.

“After a stroke, patients go to rehab to regain function in their limbs,” Cho said. “This is rehab for your sense of smell.”

So how does it work? Does he write a prescription for particular kits? How long does it take?

Kits are easy to find. Essential oils work, too.

No prescription is necessary, Cho says, and since the explosion in cases of smell dysfunction during the COVID pandemic, kits are easily accessible in stores or online. “It’s very easy to get access,” Cho said. A specific kit is not necessary. For instance, many people have essential oils at home. “You can absolutely use essential oils,” he said.

What smells do I need?

“We recommend four smells at a minimum, although if you have more, that is great,” Cho said. These represent different types or categories of smell in order to stimulate a range of olfactory neurons:

- a fruity, sweet smell (usually lemon)

- a flowery smell (rose)

- a spicy smell (clove)

- a resinous smell (eucalyptus)

Consistency is the key.

“The most important thing is consistency,” Cho said. “You have to do it every day” for several weeks. “But it doesn’t take a lot of time: two or three minutes in the morning and two or three minutes in the evening.”

Find the right location and mindset.

Cho recommends that patients do the training in a warm room (warmth helps open the nasal passages) and “get in a zen place” of calm mentally. They should hold the tube under the nose for 30 seconds and concentrate, then move on to the others, one by one. Patients should not make an exaggerated inhalation — “just breathe normally,” Cho said. “Think about the smell, even if you can’t smell that well” or at all, at first, Cho said. “Once you can smell it well, move the tube farther away.”

Beyond the specific olfactory training time, Cho advises patients to take other opportunities to work on their sense of smell. “If you are drinking tea, put in a lemon or orange peel,” he said. “If you go to a restaurant, try to pay attention to the different smells.”

Cho demonstrates how to hold and inhale scents as part of smell training — not too close to the nose, and no exaggerated deep inhaling. "Get in a zen place" of calm mentally and think about the smell, even if you can't smell it, he said.

Cho demonstrates how to hold and inhale scents as part of smell training — not too close to the nose, and no exaggerated deep inhaling. "Get in a zen place" of calm mentally and think about the smell, even if you can't smell it, he said.ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

4. Smell training can have another benefit: improved cognition.

Regaining a sense of smell is important to a patient’s quality of life, and it is also a safety issue, Cho said: “Smell is a form of emotional support, but it also warns you” about gas leaks, rotten food and other dangers. “It protects you from becoming sick.”

But there is another intriguing benefit to smell training. “There is extensive evidence that olfactory training can improve cognition, even in people without smell loss,” Cho said.

In February 2023, Cho and a group of UAB researchers led by David Vance, Ph.D., professor in the School of Nursing, published a thought-provoking review paper: “Does olfactory training improve brain function and cognition? A systematic review.”

In their abstract, the authors wrote: “Research suggests a dynamic neural connection exists between olfaction and cognition. Thus, if OT [olfactory training] can improve olfaction, could OT also improve cognition and support brain function?” To address that question, they examined 18 scientific papers, concluding that “the reviewed studies provided emerging evidence that OT is associated with improved global cognition, and in particular, verbal fluency and verbal learning/memory. OT is also associated with increases in the volume/size of olfactory-related brain regions, including the olfactory bulb and hippocampus, and altered functional connectivity.” What is even more intriguing, the authors wrote, “these positive effects were not limited to patients with smell loss … normosmic (i.e., normal ability to smell) participants benefited as well.”

As a next step in their research, the UAB investigators are hoping to launch a clinical trial in patients with HIV, who often suffer from early cognitive decline.

5. Parosmia: Bad smells can be worse than no smell — but a new treatment may help.

As mentioned in point No. 2 above, a subset of patients with olfactory dysfunction do not lose their sense of smell. Instead, it is altered — usually for the worse. “Everything smells terrible,” Cho said. One of his patients described the odor as “wet dog.” The smells can be so off-putting that many patients “are not able to eat or drink, and there can be severe weight loss,” Cho said. “One patient described taking seven showers a day, trying to get rid of the smell.”

"Gabapentin improves Parosmia (distorted smell) after COVID19 infection" now published as a research note at IFARhttps://t.co/9VNp1SHgaL@UAB_OTO #parosmia #COVID19 #uabsmell&tasteclinic #dysosmia #smellloss

— DO-YEON CHO (@dycho98) December 16, 2022

Patient witness video attached!! pic.twitter.com/hzCMOAOjWI

Between August 2021 and February 2022, for instance, more than 16 percent of the 85 patients with post-COVID olfactory dysfunction who came to the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic reported parosmia as their major symptom.

The biological cause of parosmia needs much more study; but it comes down to “an issue of how certain odors are interpreted in the brain,” Cho said. “We think this may happen when smell nerves are recovering and they go to the wrong parts of the brain and become overactive, firing too much.”

Cho recommends smell training for these patients, but he has also used drug treatment — specifically the anti-seizure medicine gabapentin — with significant success. In 2022, Cho published a paper about a small clinical trial in his clinic. Over the course of the trial, gabapentin was prescribed to 12 patients; two did not tolerate the medication because of the drowsiness that it causes, and one patient did not complete the full course of treatment. But of the nine patients who completed the study, eight showed improvement and six patients (66 percent), all of whom had parosmia with a foul smell, reported significant improvements. “They did really well,” Cho said. “It shows that, in certain people, medications can help.”

In addition to testing, diagnosis and treatment, Cho and Bramel take time to listen to their patients' experiences. "Smell loss or smell dysfunction is very frustrating," Cho said. "Counseling is really important."

In addition to testing, diagnosis and treatment, Cho and Bramel take time to listen to their patients' experiences. "Smell loss or smell dysfunction is very frustrating," Cho said. "Counseling is really important."ANDREA MABRY | University Relations

6. Patients need help — and hope.

Cho spends 30 minutes to an hour with each patient, much of it listening to their experiences. “Smell loss or smell dysfunction is very frustrating,” he said. “They have gone to other doctors who said, ‘Yes, you have smell loss; there is nothing you can do.’ Counseling is really important. Many of the patients end up crying while they are talking about their symptoms.”

The outlook for most patients is ultimately positive. “After two years, about 80 percent to 90 percent recover,” Cho said. And since the odds of success with smell training are fairly high, and the cost in time and money is so low, “it is always worth giving it a try,” Cho said.

But that still leaves the 10 percent to 20 percent of patients who may never recover their sense of smell. Cho is starting a patient support group this summer that will be open to anyone with smell loss. “Patients know there is no magical treatment yet that can immediately fix the problem, but they can learn from each other and help each other,” Cho said.

Story continues after box

Related: What happened to my sense of smell?

Cho discussed treatment options after losing smell with COVID in this UAB Medicine video.

7. We still have a lot to learn about smell.

Research on new treatments for smell loss and the underlying causes of the problem has been turbocharged by the COVID pandemic. Cho says the UAB Comprehensive Smell and Taste Clinic will be participating in clinical trials and continue to collaborate with other UAB researchers to address puzzling questions. The clinic has created a database that will help researchers understand the financial impact of smell and taste disorders and lead to new research directions as well. “This is something we are very interested in,” Cho said.