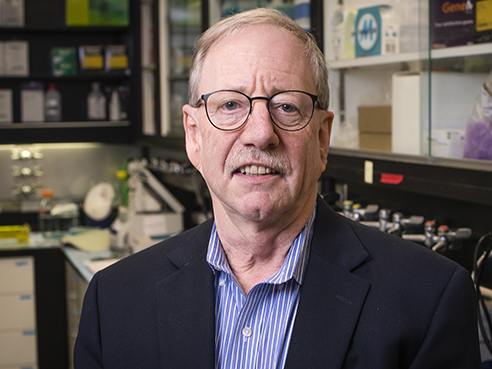

Steve Austad, Ph.D., poses with a young opossum on Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Steve Austad, Ph.D., poses with a young opossum on Sapelo Island, Georgia.

The question came to him while he was looking at an opossum.

It was catalogued as Opossum No. 9, and it lived in Venezuela. Steve Austad, working in the South American country as a postdoc, had first captured the animal a few months before. The average opossum has a lifespan of just 1-2 years, and Austad was struck by how fast the marsupial had aged.

“A few months before, it had been a vigorous, healthy adult, but a few months later it had cataracts, muscle loss and arthritis,” Austad said. And then he had a thought:

“Why would an animal the size of a cat age so much faster than a cat would?”

Opossum No. 9 in Venezuela That single question proved to be a turning point in Austad’s scientific career. Now Austad, Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Biology and director of the UAB Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging, is a leader in aging research, studying the fundamental mechanisms that control aging in humans and other life forms. His long-term goal? To develop treatments that slow the aging process, thus keeping people fit and healthy longer.

Opossum No. 9 in Venezuela That single question proved to be a turning point in Austad’s scientific career. Now Austad, Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Biology and director of the UAB Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging, is a leader in aging research, studying the fundamental mechanisms that control aging in humans and other life forms. His long-term goal? To develop treatments that slow the aging process, thus keeping people fit and healthy longer.

“Previously in my scientific career, whenever I thought I had something figured out, I’d lose interest,” Austad said. “That was 35 years ago, and I haven’t figured out aging yet.”

But he certainly has worked at it: Austad’s research has been consistently funded for more than 30 years. He has been the principal investigator on dozens of grants, including a number of multimillion-dollar projects, and through his work at the Nathan Shock Center — one of only six such centers in the United States — he has received almost $4 million in grant funding in addition to millions more in direct funding through the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health.

Austad’s commitment to his research has earned him this year’s Ireland Prize for Scholarly Distinction, presented annually by the UAB College of Arts and Sciences to a full-time faculty member for professional and academic achievements and contributions to the university and local community.

“Previously in my scientific career, whenever I thought I had something figured out, I’d lose interest. That was 35 years ago, and I haven’t figured out aging yet.”

New journeys

Before the opossum, there was a big cat.

While living in New York and working as a taxi driver in the 1970s — he hitchhiked to the city after graduating with a degree in English literature from UCLA, figuring the cab-driving gig could give him the experiences required to write the Great American Novel — he met a man who raised lions and tigers both as exotic pets and for film roles. When one of the lions booked a spot in a production in Los Angeles, the man asked Austad to help with transport.

The two loaded the caged cat into a sedan and disembarked on the week-long journey across the country. When they arrived in LA and dropped off the lion, Austad says he was met with what he simply calls a “strange” opportunity: to stay behind in the California city and work in the movie business as an animal trainer. A lifelong pet-lover and fan of the outdoors, Austad took the gig, training mostly lions and tigers, sometimes bears, and meeting celebrities such as Tippi Hedren for around three years.

Austad with lions Boomer (top and bottom left) and Hudu (right), in California.

“Hollywood was boring except for the animals,” said Austad, who “thought about studying animals in a more scientific and systematic sense.” So he decided to return to school.

He earned his bachelor’s degree in biology from California State University Northridge, then tried to marry his animal-training background with a well-known lion study happening in Africa at the time. When that didn’t pan out, Austad decided to go back to his roots. Before landing on an English lit degree at UCLA, he’d chosen a mathematics major based on sheer aptitude, so while working on his doctorate in biological sciences at Purdue University, he studied the role of game theory, or the study of mathematical models of strategic interaction among rational decision-makers, in animal combat.

His postdoctoral studies took him across the United States and to countries such as Micronesia and Papua New Guinea — and Venezuela, home of the marsupial that started it all.

Continuing the work

Austad in Venezuela with pet chicken Henny PennyAfter the opossum and the big cat came a fly, a mouse and a worm — and questions about them. Austad found that, as he began to study aging, his unusual background gave him special insights into the animals most commonly used in scientific and clinical research.

Austad in Venezuela with pet chicken Henny PennyAfter the opossum and the big cat came a fly, a mouse and a worm — and questions about them. Austad found that, as he began to study aging, his unusual background gave him special insights into the animals most commonly used in scientific and clinical research.

“I noticed all the medical researchers tended to focus on three different animals: the mouse, the fly and the worm. But there are thousands of species out there that could tell us something different about aging. Why is no one looking at those?

“I might pick an animal because it ages exceptionally fast, like the possum, or I might study animals that age exceptionally slow, slower than humans even — and what might we learn about being able to change the rate of aging and animals that age slowly?”

He also works to understand how the sexes differ in aging. Experimental drugs to slow aging often work in only one sex but not the other, he explains, which provides insights into the aspect of biology researchers and clinicians may not have appreciated before.

“We tend to assume the two sexes respond to drugs the same way,” he continued. “That may turn out not to be true, and it might be the first level of personalized medicine that comes along; we’ll have to think about treatments differently if we happen to be treating men or women.”

Spreading the word

But what Austad is most proud of, he says, is the measurable effect he’s had on how aging research is studied and conducted. His 1997 book, “Why We Age: What Science Is Discovering about the Body’s Journey Through Life,” has been translated into Chinese, Taiwanese, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, Italian, Spanish, Czech and Russian. He also has published a dozen book chapters and more than 160 articles in peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Zoology, Nature Genetics and Neurobiology of Aging, and he serves on the editorial boards of a number of prestigious journals, including Experimental Gerontology, Evolution and Medicine and Public Health, among others.

Austad in his laboratory in Volker HallHe added that his desire to communicate science to the general public, which he believes comes from his English literature background, has characterized much of his career outside of his research pursuits. He has designed several museum exhibits and authored nearly 200 newspaper columns and magazine articles — such as a column for al.com on DNA testing, where he shares how he discovered he has more Neanderthal genes than 99.9% of living people, or a My San Antonio article on the 1880s quack doctor John Romulus Brinkley, who promised surgically transplanting goat testicles into humans was the cure for aging pains.

Austad in his laboratory in Volker HallHe added that his desire to communicate science to the general public, which he believes comes from his English literature background, has characterized much of his career outside of his research pursuits. He has designed several museum exhibits and authored nearly 200 newspaper columns and magazine articles — such as a column for al.com on DNA testing, where he shares how he discovered he has more Neanderthal genes than 99.9% of living people, or a My San Antonio article on the 1880s quack doctor John Romulus Brinkley, who promised surgically transplanting goat testicles into humans was the cure for aging pains.

“I’m most proud of the way I’ve been able to move the scientific field, but at the same time, help inform the public about how we do science and why it’s important. That’s where my satisfaction comes from,” he said.

Austad says that working at UAB affords him endless chances to continue to do important work. “The reason I came here and the reason I stay here is that I feel like I can make a difference here,” he explained.

“UAB is moving in such a positive direction in so many ways, and being a part of moving it in those positive directions is gratifying,” he said. “Our science is getting better, our student body is better and better-prepared, and we’re graduating people who are better and better-trained.”

“Our international and national reputation is growing like crazy,” he continued. “I love to bring people down for seminars, friends from big-name schools, and they say, ‘Whoa, this place is really something.’ I say, ‘Yeah, take it back to where you go and let everyone know.’”

The COVID effect

The COVID effect