Riding bulls will not preserve your brain. But watching them might. UAB researcher David Vance will explain.

Riding bulls will not preserve your brain. But watching them might. UAB researcher David Vance will explain.

This is not David Vance’s first rodeo.

A few years ago, when bull riders were coming to town, the UAB School of Nursing professor decided to go see the show. “That way, I’d always be able to say, ‘This isn’t my first rodeo!’” he recalled with a laugh.

The outing was more than a joke, however. Vance, who is associate dean for research and scholarship in the school, has spent the past several decades studying ways to keep the brain healthy as it ages. He has published on electrical brain stimulators, binaural beat technology, testosterone replacement, psychostimulants, smell tests and computer games. With the notable exception of computer brain training (much more below), he has found that tech doesn’t have much of an effect. But relatively simple things, like staying open to new experiences, can have a surprisingly large impact.

“Years of education, leisure time activities, job complexity — all of that is part of your enriched environment,” Vance said. “The basic message is you don’t want to live the same day every day. You want to live a different day every day.”

David Vance knows healthy changes are difficult. But he's seen the proof that his "cognitive prescriptions" can improve brain function even in old age. "You can change behavior," he said. "You just have to be very specific with your goals to see behavior changes.”Routines help build habits; but stay in them too long and your brain will be on automatic pilot. That’s the sign of a poorly stimulating environment. So, take a new route to work. Be open to new experiences. Brush your teeth with the opposite hand. “There’s a whole field of research on personality and cognition,” Vance said. “Those people with the personality trait of openness to experience tend to have better cognitive outcomes and executive function. When you are open to experience you are also learning new things and that is good for the brain.”

David Vance knows healthy changes are difficult. But he's seen the proof that his "cognitive prescriptions" can improve brain function even in old age. "You can change behavior," he said. "You just have to be very specific with your goals to see behavior changes.”Routines help build habits; but stay in them too long and your brain will be on automatic pilot. That’s the sign of a poorly stimulating environment. So, take a new route to work. Be open to new experiences. Brush your teeth with the opposite hand. “There’s a whole field of research on personality and cognition,” Vance said. “Those people with the personality trait of openness to experience tend to have better cognitive outcomes and executive function. When you are open to experience you are also learning new things and that is good for the brain.”

If you’re reading this at work, you’re already doing one thing right. But the good news, as Vance has pointed out in a stream of research studies, reviews and articles, is that there are actually lots of different ways to keep your brain healthy as you age such as physical and mental exercise, health eating habits and quality sleep. In a 2011 article in the Journal of Gerontological Nursing, Vance introduced the concept of the “cognitive prescription” — a set of detailed, do-able lifestyle recommendations that support brain health. This is based on his training as a psychologist and his time working in behavioral research centers and with Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. “When you go to the doctor and hear, ‘You should lose a little weight,’ that may be true but it’s meaningless because that is a nebulous target goal,” Vance said. “People are responsive when we have a set target goal and we monitor our progress, even if we don’t reach the target. You can change behavior. You just have to be very specific with your goals to see behavior changes.”

No matter how old you are or what your family history is, you can sharpen your brain to fight against dementia — by removing some bad lifestyle behaviors from your day and adding more healthy behaviors. Even better, the most effective methods may cost you some sweat but are otherwise free or inexpensive. Best yet, UAB benefits make it easy to put these principles into practice.

Are you scared yet?

“As people age, pretty much the No. 1 fear is losing their cognitive abilities — their ability to think and take care of themselves,” Vance said. In a National Poll on Healthy Aging survey conducted by the University of Michigan in October 2018, 37% of responding adults ages 50-64 said they had a family member (living or deceased) with dementia, and just under half (48%) thought they were likely to develop dementia themselves. Among those with a family history of dementia, 73% thought they would get it.

One thing few were doing, however was discussing the problem with their doctors. Just 10 percent of those with a family history of dementia had talked with their doctors about ways to prevent it; overall, that number was just 5 percent. (The actual percentage of adults 65 and older living with dementia in the United States in 2012, according to a 2018 study, was 10.5%.)

That isn’t to say they were doing nothing — 73% reported they were doing something to maintain or improve memory:

- 55% said they were doing crossword puzzles or other brain games

- 48% said they were taking vitamins or supplements

- 32% said they were taking fish oil or omega-3 pills

This is not the best way to protect your brain.

This is not the best way to protect your brain.

Fighting dementia: what works?

But crosswords and fish oil aren’t the only — or, in fact, the best — ways to beat dementia. Most of us have bad habits that are doing far more to accelerate brain problems than prevent them.

Over the years, Vance has helped to clarify the factors, bad and good, that contribute to dementia risk. He is happy to share what seems to work best and the ways he applies these findings in his own life. It’s an approach that can be summarized like this:

- Your brain is always changing — either negatively or positively.

- Boosting cognitive reserve can delay dementia symptoms.

- You can eliminate negatives by treating chronic diseases and depression.

- You can add positives by learning and cognitive training.

- Remember, what’s good for the body is good for the brain.

BFFs and brain changes

You may not like to talk much, but your brain certainly does. Packed inside your skull are some 100 billion neurons. Unlike intestinal cells, which live only a few days, or skin cells, which turn over every few weeks, these billions of brain cells are exactly as old as you are. Barring injury or disease they will be with you until you die, so taking care of them should be a top priority.

What have your neurons been doing all these years? Making connections. Every time you form a new memory, or practice a skill, new connections between neurons are formed or strengthened. They have lots of room for growth; a single neuron can build several thousand physical links to other neurons. But these connections are like friendships. If you don’t reinforce a concept or skill by working at it, the links between cells can fade or disappear for good.

Cognitive reserve is king

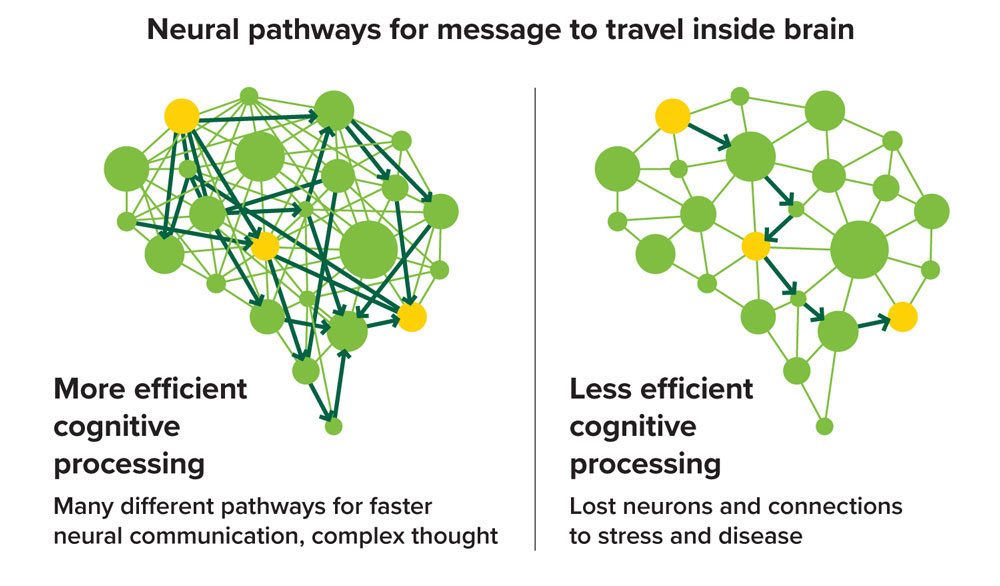

In a fascinating review article in 2013, Vance put forward a theory of how this all works, based on the idea of cognitive reserve. Cognitive reserve, he explained, “refers to the complexity, efficiency and strength of the neural connections in the brain… The more intricate and efficient these connections, the faster neural communication is transmitted and the more complex the thoughts that can emerge from such communication.”

Cognitive reserve also is protective, he added. If neural connections are lost because of disease, disuse or traumatic brain injury, Vance explained, “information can be rerouted through alternative neural pathways so that neural information can still be communicated and cognition can continue to function.”

Vance included a simplified diagram, reimagined below, to help readers visualize the process. Say the goal is to get a message from Level 1 down to Level 3 — the message might be “Watch out for that jaywalker!” for instance or “What’s a six-letter word for style?”

The brain on the left can send this message down many different pathways. Some are more heavily used, represented by darker arrows that represent learning, or routines. But, in a pinch, there are many other options. The brain on the right, which has lost neurons and connections to stress and disease, is much less efficient. Messages travel slower. Thinking is harder.

Changes every day

“The greater one’s cognitive reserve (i.e., number and strength of connections between neurons),” Vance wrote, “the more one is able to withstand neurological insults and maintain cognitive efficiency.”

What determines your cognitive reserve? In studies, researchers often use years of education as a proxy, but it’s not that simple. Health status, stress, negative emotion, substance use, genetics and environment (including educational history) all play a role. In fact, “everything we do in everyday life affects cognitive reserve — whether you build it up or tear it down,” Vance said. “Our brains are constantly reforming. The way I see it, you can push them in positive directions by doing good things and in negative directions by doing bad things or doing nothing.” He coined the terms positive neuroplasticity and negative neuroplasticity to get the point across.

"Everything we do in everyday life affects cognitive reserve — whether you build it up or tear it down,” Vance said. “Our brains are constantly reforming. The way I see it, you can push them in positive directions by doing good things and in negative directions by doing bad things or doing nothing.”

"Everything we do in everyday life affects cognitive reserve — whether you build it up or tear it down,” Vance said. “Our brains are constantly reforming. The way I see it, you can push them in positive directions by doing good things and in negative directions by doing bad things or doing nothing.”

Take your medicine

The positive elements of neuroplasticity — crosswords and so on — get all the attention, but it is our bad habits that could play the largest role. Chronic health conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes or HIV are a major factor, Vance said.

Pop quizCount backward from 100 by sevens. – Sample question from the Mini-Mental State Examination, another test frequently used in studies of cognitive reserve. (Subjects are asked to stop after five answers.) |

He points to two studies by UAB’s Virginia Wadley Bradley, Ph.D., drawing data from the massive UAB-led REGARDS study. In a 2019 paper, Bradley and colleagues examined effects on the brains of tens of thousands of participants in a large cohort of aging Americans. During eight years of follow-up, the researchers noted that higher blood pressures were associated with faster declines in cognition. In black participants, and in men, higher levels of systolic blood pressure were associated with faster declines in global cognition and new learning, respectively. A 2018 study by Bradley and colleagues showed that this damage could be improved. They found that lowering systolic blood pressure to 120 mm HG or less reduced the risk of mild cognitive impairment and in turn reduces risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or dementia.

Similar research has shown damaging effects of untreated diabetes and HIV, Vance noted. But patients who were taking their medications scored on a similar level as their age-matched peers when they were taking their medications as directed.

“People with hypertension have increased risk of cognitive decline — unless they’re taking their medication,” Vance explained. “I have hypertension and I am taking my medication and check my blood pressure at home regularly. Seemingly little health behaviors matter a great deal.”

Deal with depression and anxiety

“There’s a mountain of literature on the effects of depression and anxiety on brain health and thinking,” Vance said. “When you have prolonged depression, it damages the brain.” Essentially, “when you don’t have good coping skills you are always in this fight-or-flight mode,” Vance said. “That means you are producing a lot of a hormone called cortisol and over time that leads to neurotoxicity and negative mental consequences.”

The cortisol flood “is reducing the viability of those neurons,” Vance said. “Even if the connections are still there, it’s wear-and-tear on the neurons and on the glial cells that support the neurons.”

Why intellectual exercise matters — and hobbies, too

Several studies have found a strong correlation between years of education and risk of dementia. “There is a lot of research that shows that people who are intellectually stimulated and learning new things are getting intellectual exercise and promoting positive neuroplasticity,” Vance said. The more education a person has had, the greater the intellectual stimulation they have received and, the hypothesis goes, the more cognitive reserve he or she has built up.

“When you are learning your brain is hyper-stimulated,” Vance explained. But greater benefit comes from learning something new (the thinking behind the recommendations to learn a foreign language). “At some point we habituate,” Vance said. “We’re at a higher level than before, but we don’t get any more benefit.”

Pop quizGiven a handful of change — 3 quarters, 4 dimes, 3 nickels and 4 pennies — count out 67 cents and place it on the table in front of you. – Sample task from the Timed Instrumental Activities of Daily Living assessment, used in the ACTIVE study. |

In a 2008 study, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine used PET scans to measure buildup of protein plaques (associated with Alzheimer’s disease) in the brains of 198 adults with and without Alzheimer’s. Participants who had high levels of education performed better on cognitive tests such as the Mini-Mental State Exam, even when they had large amounts of beta-amyloid plaques. Education and intellectual exercise “doesn’t protect you from getting Alzheimer’s but it might delay it by a couple of years,” Vance said.

The most striking example of the effect of learning on the brain comes from the London taxi driver study. In a 2006 paper, researchers at University College London examined the brains of bus drivers and taxi drivers in London. London cabbies have a famously rigorous test and train for up to 4 years to memorize the layout of 25,000 streets and thousands of landmarks. Bus drivers, by contrast, drive a fixed route. When the researchers matched individuals from both groups by stress level and years of driving experience, the taxi drivers tended to have a larger hippocampus, a part of the brain heavily involved in memory. The more experience a taxi driver had, moreover, the larger the hippocampus.

It doesn’t take years of practice to see a benefit, either. In 2008, a group of German researchers taught 25 older adults, average age 60, how to juggle. They took MRI scans before the lessons, three months later when they had learned the skill, and three months after that, with no practice to keep up the skill. Compared to baseline, MRIs taken immediately after learning to juggle showed growth in the hippocampus and the nucleus accumbens, another brain region involved in memory consolidation. But they had to keep practicing. A third set of MRI scans taken after the participants were told to stop practicing juggling showed “a loss of volume in these same brain structures,” the researchers wrote.

Brain training works

Apart from dementia, one of Americans’ other biggest fears is losing their right to drive, Vance said. And research shows they have a reason to be worried. “There’s so much literature on what happens to people after they have to reduce their driving,” Vance said. “They experience depression and loss of daily function. Here in the South especially it’s a big deal because of the lack of public transportation, especially in rural areas.”

But a growing number of studies by Vance and other researchers point to a way to delay the day we have to surrender the keys. Computer games — specifically, a type of game known as speed-of-processing training, originally developed by UAB psychology Professor Karlene Ball, Ph.D. — do work, they have found.

Speed-of-processing “is the ability of how much information you can take in at a moment’s glance,” Vance said. “If you can expand that, it’s a big deal. That makes you more aware of your visual environment automatically.” The training program used in Ball and Vance’s studies is now offered as part of a “BrainHQ” subscription from the company Posit Science. Called Double Decision, the game challenges players to identify a vehicle in their central vision while at the same time keeping track of other objects flashing by in their peripheral vision. The applications to driving skills are obvious. “It’s really hard,” Vance said. “It’s supposed to make your brain sweat. It’s just like the gym: if you don’t put in the work you don’t get the results.”

[You can give Double Decision a try at this link — https://www.brainhq.com/welcome#assessment/speedtest — or watch a video explaining how the game works below.]

And the results are impressive. “We already know that people who go through speed-of-processing training are in fewer accidents,” Vance said. These findings come from the ACTIVE study, a long-term research project at UAB and six other institutions that followed more than 2,800 volunteers who received speed-of-processing training, memory training or reasoning training.

A 2010 paper by Ball, based on ACTIVE data, found that 10 speed-of-processing training sessions cut a person’s risk of being at fault in a motor vehicle accident in half. That training was also associated with even more profound effects. A 2017 paper by a group of researchers including former UAB faculty member Jerri Edward, Ph.D., now at University of South Florida, reported that a decade after their 10 training sessions, the speed-of-processing training group had a 29% lower risk of dementia.

Pop quizName as many animals as you can in one minute. - Brief test used clinically to evaluate memory function. Normal score is 21 or more. |

“We don’t have a pill that can do that,” Vance said. “The increase was even bigger for the people who received the speed-of-processing booster training.”

Vance has submitted a major NIH study testing speed-of-processing training in breast cancer survivors. The treatments that allow patients to survive are also associated with a high rate of cognitive difficulties, unfortunately. These side-effects of forgetting and mental fuzziness are commonly referred to as “chemo brain.” “A report by a Cochrane Review said cognitive training was needed in this group,” Vance said. His study aims to investigate what speed-of-processing training can do in this patient population. “I already feel like this is a very good and accessible intervention in terms of the outcomes we’ve seen in other studies,” Vance said. He has also shown positive effects for speed-of-processing training in HIV patients and is concluding another large NIH study in adults with HIV who suffer accelerated cognitive decline.

“You can’t play and have your IQ go up by 10 points, or I would be playing it all the time,” Vance said. “But with practice, you can improve certain cognitive skills and that has ripple effects in the brain and in everyday functioning.”

What’s good for the body is good for the brain

“Everything that’s going on with the body affects your brain,” Vance said. “When you don’t sleep well, you know that you won’t think as well. But not as many people know that exercise and diet and rest can improve your cognitive reserve as well.”

Exercise

In fact, exercise may be the single most effective “positive” for neuroplasticity “because it generalizes so much to overall health,” Vance said. “It really gets to the base of your biology. Exercise gets your natural endorphins going, helps with anxiety and depression, and it has a social component to it if you do it with others.”

In a 2016 study of 122 older adults, Vance and UAB colleagues reported that participants who were more physically active had lower levels of depression and better cognitive functioning than their more sedentary counterparts.

A 2017 study by Virginia Wadley and Virginia Howard, Ph.D., at UAB, and colleagues elsewhere, examined nearly 6,500 older adults. Those who spent more of their time in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity had a 36% lower risk of cognitive impairment compared with those who were less active. They also maintained their memory and executive function at higher rates as they aged.

Diet

Extra weight puts extra stress on the body and can make conditions such as diabetes and hypertension worse. But it also can have a more direct effect on the brain through inflammation, Vance said.

A Spanish study, in 2009, summarized the evidence of a link between good nutrition and cognitive function through reduced inflammation. The Western dietary pattern is pro-inflammatory, packed with refined starches, sugar and saturated and trans-fatty acids and low in inflammation-fighting antioxidants and fiber from fruits, vegetables and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet, which is marked by regular consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, olive oil and fish, meanwhile, is linked with reduced inflammation. The researchers reported that “even a modest effect of nutrition on cognitive decline could have significant implications for public health.”

In 2013, UAB researchers looked at the diets of nearly 17,500 African-Americans and Caucasians enrolled in the UAB-led REGARDS stroke study. Participants who ate something similar to the Mediterranean diet were 19% less likely to develop problems with thinking and memory skills over the course of the study.

Sleep

Insomnia or trouble getting to sleep or staying asleep is a common complaint with age, affecting as many as 50% of older adults.

Lack of sleep affects cognitive skills as well, as nearly everyone has experienced. “If you didn’t get a good night’s sleep, you know you’ll have trouble focusing and processing information the next day at work,” Vance said. Sleep troubles can affect a person’s results on cognitive tests as well, he added. “Some of these tests are sensitive. If you didn’t get a good night’s sleep, that can affect the results.”

But it is possible to improve, according to a 2017 report from researchers in Brazil. The investigators found that cognitive training exercises improved sleep quality as well as measures of cognitive flexibility, problem solving, verbal fluency and memory in a group of healthy older adults.