The Woodward Iron Company (above) and other industrialists in Birmingham opted to reduce their employees' hours rather than lay them off, hoping demand would eventually increase due to market fluctuations.Decades before Birmingham’s tumultuous involvement with the civil rights movement, another political shift was taking place in the Magic City: the rise of communism.

The Woodward Iron Company (above) and other industrialists in Birmingham opted to reduce their employees' hours rather than lay them off, hoping demand would eventually increase due to market fluctuations.Decades before Birmingham’s tumultuous involvement with the civil rights movement, another political shift was taking place in the Magic City: the rise of communism.

In the late 1920s, the Communist Party U.S.A. chose Birmingham for its new District 17 headquarters. The city — the nerve center of the industrial South — was the ideal home base for the district, which comprised Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, Tennessee and Mississippi. Add to that the large number of laborers and African-Americans tired of inequality and wealth disparity, and Birmingham was primed to be the seat of the Southeast’s communist party activities, said Pam Sterne King, assistant professor of history.

King has chronicled Birmingham’s involvement in the growth of the communist party aided by students who documented the sites most integral to it during the HY 481 Public History course. She chose the topic for the spring course because she believes knowledge of the city’s role in the early 20th century communist movement is needed to understand other aspects of Birmingham’s history.

“Because of Birmingham’s tight-fisted industrial history and history of civil rights [abuses], it makes sense there had to be a piece that came before that,” King said. “I think that the communist movement in Birmingham helps to answer the question of why the civil rights movement had to happen here.”

Finding fertile ground

The American South in the early 1900s was a fertile ground in which communism could grow and spread. Alabama in particular was a “cauldron of class conflict” in the early 20th century, according to Robin D.G. Kelley’s “Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression,” which King’s students used to research material for the class.

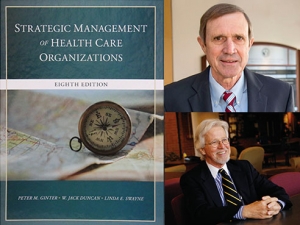

In Birmingham in 1910, only 1 percent of the population was worth more than $35,000, and 80 percent earned less than $500 annually. That same 1 percent also held economic and political power in the area, Kelley wrote. Communism, a movement based on the ideas of the absence of money, social classes and the state coupled with common ownership of the means of production, seemed like the answer to the disparities in Birmingham and across the South. The Clark Building, at 20th Street North and 4th Avenue North, was once home to the headquarters of Birmingham's communist party. Pam King (left), assistant professor of history, and her HY 481 students researched sites in Birmingham connected to the communist party in the 1930s and '40s.During the Great Depression, the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company and the Woodward Iron Company resorted to essentially forced labor to keep their businesses afloat, according to Kelley. Miners and steelworkers often worked fewer than three days per week, lived in company-owned settlements and were paid wages in scrip accepted only at the company commissary. The refusal to lay off workers while simultaneously binding those workers to the company through housing and wages ensured the businesses survived, but it was a driving force behind many laborers’ interest in the communist ideals.

The Clark Building, at 20th Street North and 4th Avenue North, was once home to the headquarters of Birmingham's communist party. Pam King (left), assistant professor of history, and her HY 481 students researched sites in Birmingham connected to the communist party in the 1930s and '40s.During the Great Depression, the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company and the Woodward Iron Company resorted to essentially forced labor to keep their businesses afloat, according to Kelley. Miners and steelworkers often worked fewer than three days per week, lived in company-owned settlements and were paid wages in scrip accepted only at the company commissary. The refusal to lay off workers while simultaneously binding those workers to the company through housing and wages ensured the businesses survived, but it was a driving force behind many laborers’ interest in the communist ideals.

The city’s first communist party headquarters — established in 1929 by Tom Johnson and Harry Jackson, two full-time white organizers and veterans to the movement — was located at 2117 ½ Second Ave. North, a three-story building still located downtown, next to popular Collins Bar. The District 17 headquarters later moved to the red-façade, two-story Clark Building on Fourth Avenue North.

Mapping a growing physical presence

|

“The communist movement in Birmingham helps to answer the question of why the civil rights movement had to happen here.” |

Throughout the 1930s, Birmingham developed into a vital regional player in the communist movement. According to “Hammer and Hoe,” as an industrial city with large numbers of relatively organized laborers, Birmingham was an ideal location for the expanding communist party. Citizens became leaders in their local chapters, lived in homes in West Birmingham, East Lake and Homewood and attended places of worship such as Wahouma’s 45th Street Baptist Church. Protests, demonstrations and large-scale meetings took place downtown at the Negro Masonic Temple on Fourth Avenue North and at Capitol Park (now Linn-Henley Park) on 20th Street North, and many demonstrators were jailed at the facility then located on 21st Street North.

King’s students identified more than 15 Birmingham sites central to communist organizers. Then they photographed the places where this activity occurred and produced a project that the public could more readily access, King said.

“The students,” King said, “came away with understanding a whole new slice of American history.”

The UAB Reporter created a special Google Map for the locations chosen by students.

Not all sites the students chose had positive associations to the communist movement; for example, the pastor of Collegeville’s Bethel Baptist Church, Rev. M. Sears, was one of the city’s leading anti-communists and the co-author of the controversial 1931 Commission on Interracial Cooperation report, “Radical Activities in Alabama.”

After Randolph “Doc” Carter, a Greenwood Red Cross relief worker and associate of Sears, went into hiding following a heated argument with a white project foreman, Sears lured him out and turned him into Birmingham police, who beat Carter. The arrest and violence incensed Collegeville and nearby Greenwood residents, and a communist-led group marched to Bethel Baptist, where, as Kelley wrote in “Hammer and Hoe,” Sears drew a shotgun from behind the pulpit, nearly causing a riot as churchgoers and protesters rushed out of the building.

This story is part of a series on UAB researchers studying communism and radical left-wing politics. In case you missed it, read about the influence of pre-revolution Russia on modern African-American politics and just how closely radicalism, race and police brutality are intertwined.