“As soon as I could read, I was writing,” Latham says. At four she started creating poems for her mother. By eight she wrote in her copy of Dr. Seuss’s My Book About Me that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up.

“As soon as I could read, I was writing,” Latham says. At four she started creating poems for her mother. By eight she wrote in her copy of Dr. Seuss’s My Book About Me that she wanted to be a writer when she grew up.When it came time for college, however, her parents advised her to choose a more practical career. “They said, ‘It’s difficult to make a living as a writer,’” Latham recalls. So she majored in social work instead, and then concentrated on marriage, career, and motherhood. But she never stopped working on her poems.

“My epiphany moment came after my third child was born,” Latham says. “I looked around at the piles of paper on my desk and spilling out of its drawers and realized that I had been doing what I was meant to do all along. Now it was time to be brave enough to share all of those words with other people.”

Words Into Type

With persistence, she succeeded, eventually becoming a contributor to the collection Poems From the Big Table. Her own collection, What Came Before, won the Alabama State Poetry Society’s Book of the Year award in 2007.“I now know that there are two kinds of bravery,” Latham says. “One kind is when you write something down on the page. The other is when you put it out there to have someone else react to it.”

Even though writing is an inherently solitary profession, the secret to finding inspiration also involves stepping out into the world and living “a life worth writing about,” Latham explains.

“One of the hazards of being a writer is spending so much time inside, all alone, typing, when actually the seeds of stories are found outside, under rocks, in museums, at the park, and in virtually any moment that’s new and different and engages the writer with the world and the experience of being human.”

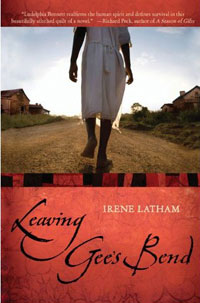

For Latham, the road to Leaving Gee’s Bend began at New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art. She went there to see an exhibit of dozens of colorful quilts made by a group of African-American women from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, a tiny community in rural Wilcox County, west of Montgomery.

Stories of Survival

The masterfully woven quilts earned international fame for the women of Gee’s Bend, but the exhibit also chronicled the town’s history of hardship. Latham was particularly struck by an incident during the Great Depression, when a shopkeeper who had extended credit to the black families in the community died. His relatives, desperate for money, called in all of those debts and took away what little the black families owned. As a result, many blacks in Gee’s Bend became destitute, sustained only by meager rations brought in by the Red Cross. “As I was reading about all of these events, I just knew that I had to write about them,” Latham says. “How do you survive that and still love humanity and love the world?” Latham poured herself into research, making repeated trips to Gee’s Bend and to the public library in nearby Camden.

“As I was reading about all of these events, I just knew that I had to write about them,” Latham says. “How do you survive that and still love humanity and love the world?” Latham poured herself into research, making repeated trips to Gee’s Bend and to the public library in nearby Camden.Leaving Gee’s Bend is an adventure story, set in 1932 and told from the point of view of 10-year-old Ludelphia Bennett. When her mother becomes ill, Ludelphia is determined to get the medicine she needs and strikes out on her own to walk to Camden, some 40 miles away.

In order to promote Leaving Gee’s Bend, Latham has been spending a lot of time on the road herself lately, speaking at schools, libraries, and writer’s conferences around Alabama and across the United States. She is also working on a second novel, Escape From Fire Mountain, which is taking her farther afield—to the Caribbean island of Martinique in 1902. The story revolves around two girls who escape the eruption of the island’s Mount Pélee. Latham is also writing a new book of poetry titled Tell Me.

“The most important things that I have learned through all of this are to be open to life’s experiences and that there isn’t one path toward any goal,” she says. “You can take the detours and still get there. Looking back, I wouldn’t change a thing.”

By Gail Allyn Short