Children often acquire S. mutans from non-family members.New ongoing research from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Biology and School of Dentistry is showing more evidence that children may receive oral microbes from other, nonrelative children.

Children often acquire S. mutans from non-family members.New ongoing research from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Biology and School of Dentistry is showing more evidence that children may receive oral microbes from other, nonrelative children.It was previously believed that these microbes were passed primarily from mother to child, but in a recent study presented at the American Society for Microbiology MICROBE 2016 Meeting in Boston, researchers found that 72 percent of children harbored at least one strain of the cavity-causing Streptococcus mutans not found in any cohabiting family members.

S. mutans is a bacterium that feeds on fermentable carbohydrates, in particular sucrose, that are frequently consumed by humans. After meals, S. mutans produces enamel-eroding acids, which makes S. mutans one of the main causes of tooth decay, or dental caries, in humans.

Study author Stephanie Momeni, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Biology at UAB, says she wanted to track the transmission of S. mutans in a first-of-its-kind large-scale epidemiological study in Perry County, Alabama. Momeni conducted her research in the laboratory of Noel Childers, DDS, Joseph F. Volker Endowed Chair and Chair of UAB’s Department of Pediatric Dentistry.

One hundred nineteen African-American children ages 12-18 months and 5-6 years who lived with at least one family member were a part of the study. The researchers collected samples from children periodically over the course of eight years. Momeni says that dental caries are more prevalent in minorities and low-socioeconomic groups.

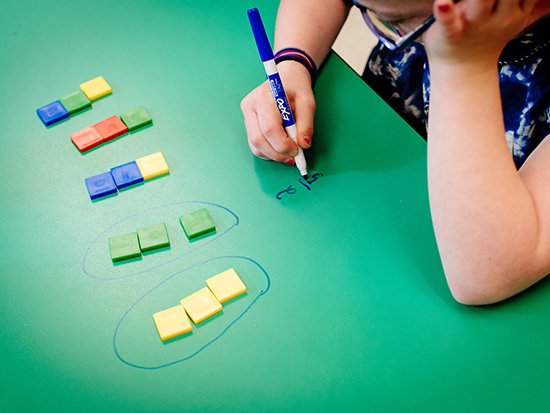

“The literature tells us that we usually get this bacterium from our mothers,” Momeni said. “This is because we most commonly have more interaction with our mothers when we are very young. However, our data supports that children who interact with other children at school or in nurseries can, and frequently do, contract this bacteria from each other.”

Momeni says any interaction that involves saliva, like sharing an ice cream cone or drinking after another child from the same cup or straw, can cause the microbes to be transferred.

“While the data supports that S. mutans is often acquired through mother-to-child interactions, the current study illuminates the importance of child-to-child acquisition of S. mutans strains and the need to consider these routes of transmission in dental caries risk assessments, prevention and treatment strategies,” Momeni said.

Forty percent of the children in the study did not share any S. mutans strains with their mothers, and close to 20 percent of children shared these bacteria only with another child who lived in the household, such as a sibling or cousin.

It is important to note that, for the strains of S. mutans not shared with anyone in the same household, approximately a third of the children had only a single isolate for a genotype, which could mean these rare strains may have nothing to do with the dental caries, and may be confounding the search for strains associated with the disease.

Further analysis with an alternate bacterial typing method is needed to confirm these findings, and it is important to note that in some rare instances not all household family members chose to participate in the study.

When Momeni discusses S. mutans, she makes a point to ease mothers’ concerns they often have of passing along oral microbes that cause tooth decay to their children.

“We’re not trying to say don’t kiss your babies,” Momeni said. “Kissing your children has important positive psychological as well as possibly biological effects on childhood development.”

Momeni is also a dental academic research training fellow in the Department of Pediatric Dentistry. This research was funded by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research.