A new study from University of Alabama at Birmingham developmental psychologist Jessica Mirman, Ph.D., offers insight into how parents can affect when their teen gets licensed.

With colleagues at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Michigan, Mirman studied more than 450 families from the time teens got their learner permits through the initial years of independent licensure. Results from the study were published this month in Health Psychology.

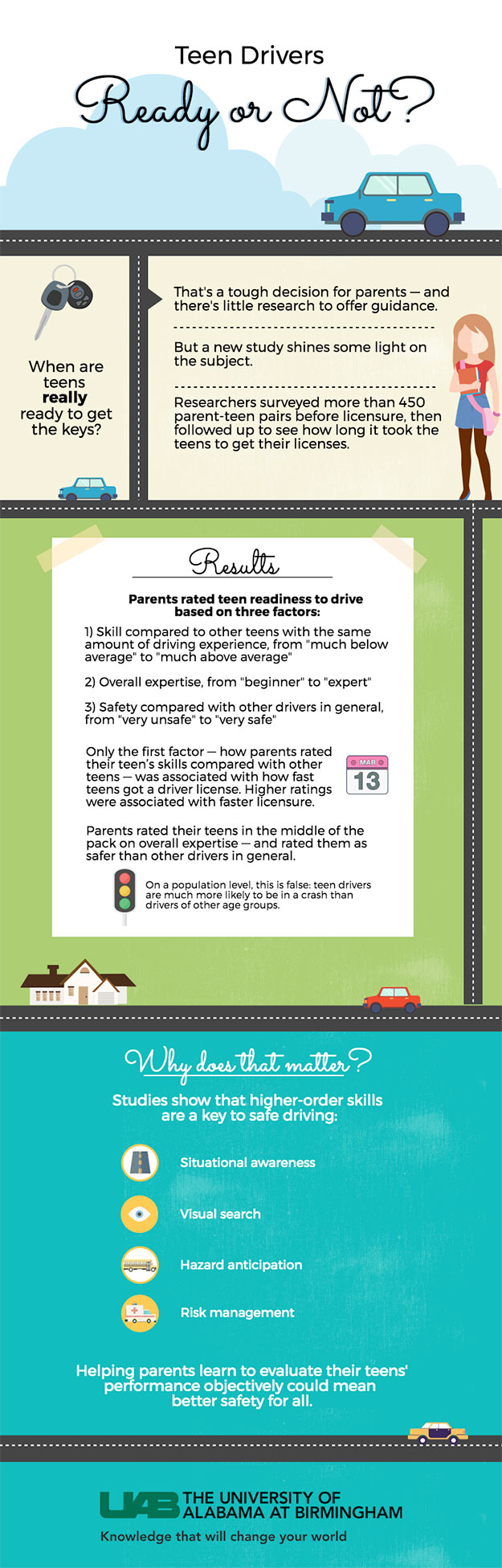

With colleagues at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Michigan, Mirman studied more than 450 families from the time teens got their learner permits through the initial years of independent licensure. Results from the study were published this month in Health Psychology.The researchers evaluated if the amount of time it took for teens to get a license was affected by parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ readiness to drive, teens’ diversity of supervised practice (i.e., the number of different environments where practice occurred), and whether or not the family participated in an Internet-based parent-supervised driving intervention program.

Each parent-child pair of participants completed periodic surveys over 24 weeks and were then followed up with to determine the teens’ licensure status. The participants were either part of a control group that did not use the intervention or part of a group that did.

“The importance of school readiness is well understood by many parents of younger children, but if you ask parents about readiness to drive, they are much less certain,” said Mirman, who is an assistant professor in UAB’s Department of Psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences. “The school readiness metrics we have for young kids just don’t exist yet for teen drivers. Most behind-the-wheel license tests really just focus on the basics of how to operate a vehicle and the rules of the road. These are necessary, but not sufficient, prerequisites for being a safe independent driver.”

Overall, the study showed that parents tended to believe their teens were as safe as, or slightly safer than, drivers in general, but these beliefs about overall safety were not related to how fast teens were licensed. Instead, licensing speed correlated with parents’ perceptions of their teen’s skill in comparison to their teen’s peers.

“The results indicate that efforts to communicate with parents about their teens’ readiness, or unreadiness, to drive will fall short in making an impact on their decision on when they should get their licenses,” Mirman said.

Instead, the authors suggest that helping parents be more sensitive to teens’ emerging skills might be more effective in promoting safe entry into licensure.

“Helping parents become more attuned to their adolescents’ emerging higher-order driving skills might be an effective approach for safe entry into licensure.” Mirman said.

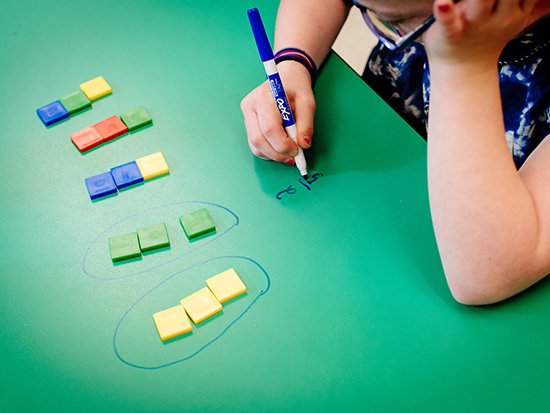

Previous studies show that higher-order skills such as situational awareness, visual searching abilities, hazard anticipation and risk management skills are important for safe driving. However, Mirman’s prior research has shown that parents don’t usually focus on these types of skills during supervised practice drives. Instead, they gravitate to the basics, like vehicle maintenance and everyday routine trips.

“Ideally, we want to see teens practicing in what developmental and educational psychologists call a ‘zone of proximal development,’” Mirman said. “This means that their driving practice is appropriately calibrated to their growing skill set and is not too easy and not too hard.”

Mirman suggests that parents find that sweet spot to practice in and continue to adjust their level of support as the teen improves and takes on new challenges.

“Professional driver evaluators can be an asset to parents because they can provide objective feedback about the areas where teens need more practice and give practical tips tailored to a family’s specific needs,” Mirman said.

The results also showed that the time it takes teens to get licensed was not affected by the parent supervised practice intervention, which was designed to increase the quality of supervised practice driving.

“This is good, because we don’t want to see interventions lessening the amount of time that teens are spending during the learner period or lead to a false sense of confidence,” Mirman said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health as part of a broader and longer-term investigation of teen drivers. Additional findings will be reported in coming months.