Photos by Steve Wood.A driver fails to notice a stop sign and collides with another vehicle. While this type of scenario is all too common, it is possible that such a crash could be prevented in advance by consulting with a driving instructor or traffic engineer or…a psychologist?

Photos by Steve Wood.A driver fails to notice a stop sign and collides with another vehicle. While this type of scenario is all too common, it is possible that such a crash could be prevented in advance by consulting with a driving instructor or traffic engineer or…a psychologist?

Yes, the UAB Department of Psychology is behind the wheel of an innovative research program designed to study driver behavior—especially among high school students—and use the gathered data to improve safety.

The UAB Translational Research for Injury Prevention Laboratory, or TRIP Lab, was founded in 2009 by Despina Stavrinos, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychology. With the help of UAB student assistants, as well as an immersive SUV driving simulator acquired in 2016, the lab delves deep into the actions of distracted drivers. The goal is to find behavioral patterns that can be altered in order to make potential accidents less likely to occur.

“I’ve always been interested in cognition and brain processees surrounding decision making and attention,” said Stavrinos. “When you think about those basic psychological processees, they develop over childhood into early adulthood. So, how do those things apply to a real-world context like driving? I’m a very applied researcher, and much of the work we do at UAB is addressing real-world problems.”

“The UAB TRIP Lab aids in creating safer and more educated communities.” — Arlene Lester, State Farm

At first glance, automotive safety might seem to be an area of research more suited to engineering than psychology. But as TRIP Lab assistant director Benjamin McManus, Ph.D., notes, “It’s still humans who are driving the car.”

“Almost all crashes are due to some sort of human error that was preventable, and the number one contributor to that human error is some sort of inattention,” said McManus. “Psychologists are trained on cognition and attention development. So, this lab looks at motor vehicle collisions through the lens of psychology, focusing on attention development and human limitations as it relates to cognition.”

The origin of TRIP Lab dates back to Stavrinos’ work in the mid-2000s with Department of Psychology University Professor David Schwebel, Ph.D., focusing on injury prevention among children as pedestrians crossing the street. Stavrinos also conducted postdoctoral work at UAB’s Injury Control Research Center (ICRC) with Russ Fine, Ph.D., Emeritus Professor of Medicine in the Heersink School of Medicine, where she founded the TRIP Lab.

Professor Despina Stavrinos“My early work was looking at attention development—how we make decisions in real time—and applying it to things like how little kids cross the street,” said Stavrinos. “I translated that into driving. Because those same kids grow up, and now they’re behind the wheel…still with an immature brain that is continuing to develop. I was intrigued to learn how immature brain processes put these kids at risk, and what can we do to increase that learning to save lives.”

Professor Despina Stavrinos“My early work was looking at attention development—how we make decisions in real time—and applying it to things like how little kids cross the street,” said Stavrinos. “I translated that into driving. Because those same kids grow up, and now they’re behind the wheel…still with an immature brain that is continuing to develop. I was intrigued to learn how immature brain processes put these kids at risk, and what can we do to increase that learning to save lives.”

Simulated Driving in a Real SUV

The ability of TRIP Lab to gather such data has accelerated tremendously over the years. When the lab began, the driving simulator was a simpler desktop computer with integrated steering wheel, brake, and accelerator—cutting edge at the time. As a result, the lab was limited in the type and amount of data it could gather, and many of the research opportunities were small, single-year projects.

That changed dramatically in 2016 when Honda Manufacturing of Alabama gave the lab a new Pilot SUV that had been built at its production facility in Lincoln, and the Alabama Department of Transportation provided funding for the creation of a fully immersive driving simulator with video screens on all sides of the vehicle. Future projects led to the addition of integrated eye tracking equipment. It is the only such simulator in the state of Alabama, and remains the only known SUV simulator in operation anywhere.

Sitting in an actual vehicle with visuals all around provides an element of realism that substantially increases the lab’s data-gathering capabilities. This is especially important since the primary focus of the lab’s studies involves teenagers born in the 21st century who have grown up on technology that is both realistic and immersive.

“With this simulator, when our participants get in it, they treat it seriously,” said Stavrinos. “So, we’re able to get a really good estimate of their real-world driving behavior.”

This enhanced ability enabled TRIP Lab to quickly secure a multi-million dollar, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the changes that take place in teenage drivers in the months immediately after obtaining their license.

“The most dangerous thing you’ll do in your lifetime is independent driving during those first months after getting your license,” said Stavrinos. “People teach teens how to drive in an empty parking lot, or have them drive a familiar route during the day in ideal conditions. Then they get their license and it’s like, ‘Here are the keys. Go.’”

Benjamin McManus meets with the TRIP Lab team.“We want to know what teens learn during those first months of independent driving, and how they acquire improved skills. That way, we can find some training targets to accelerate that learning, so we can then reduce the amount of time when they’re at their highest risk.”

Benjamin McManus meets with the TRIP Lab team.“We want to know what teens learn during those first months of independent driving, and how they acquire improved skills. That way, we can find some training targets to accelerate that learning, so we can then reduce the amount of time when they’re at their highest risk.”

Working with schools in the Greater Birmingham area, TRIP Lab brought in nearly 200 teenagers over the past five years to participate in the study. Once they become familiar with how to operate the simulator, the students take a few uneventful drives so researchers can establish a baseline of their ability.

After that, things start to get a little chaotic. Cars may suddenly brake in front of them. A cell phone rings. A text comes in. Pedestrians nearly step into the roadway.

“We can make the scenery look like a specific area, then program all these different customized scenarios for a variety of conditions,” said McManus. “We can get really detailed, including how many drops of rain per minute and how big are the droplets.”

All along, data constantly are being gathered about how the driver reacts to these distractions, and where their eye focus is in the moments immediately before an incident occurs.

“We record all their behaviors,” said Stavrinos. “When a hazard appears, how long does it take to respond? How do they maneuver around it? Do they brake? Do they swerve? What were their steering behaviors like? Their speed? Lane position? It’s a very powerful system where we get fine-grain information about their behavior.”

“Then with the eye-tracking, we’re also able to see their visual reaction. Did they even see the hazard? Were they scanning for it? People sometimes have this tunneling effect during their first months of driving, so they just stare at the car in front of them. How many times did they glance around to notice what else is out there?”

Stavrinos says the goal of the study is to shed some light on exactly how and when those improvements take place, providing specific suggestions on ways to better train students while they still have their learner's permit before becoming independent drivers.

A Safe Place to Learn

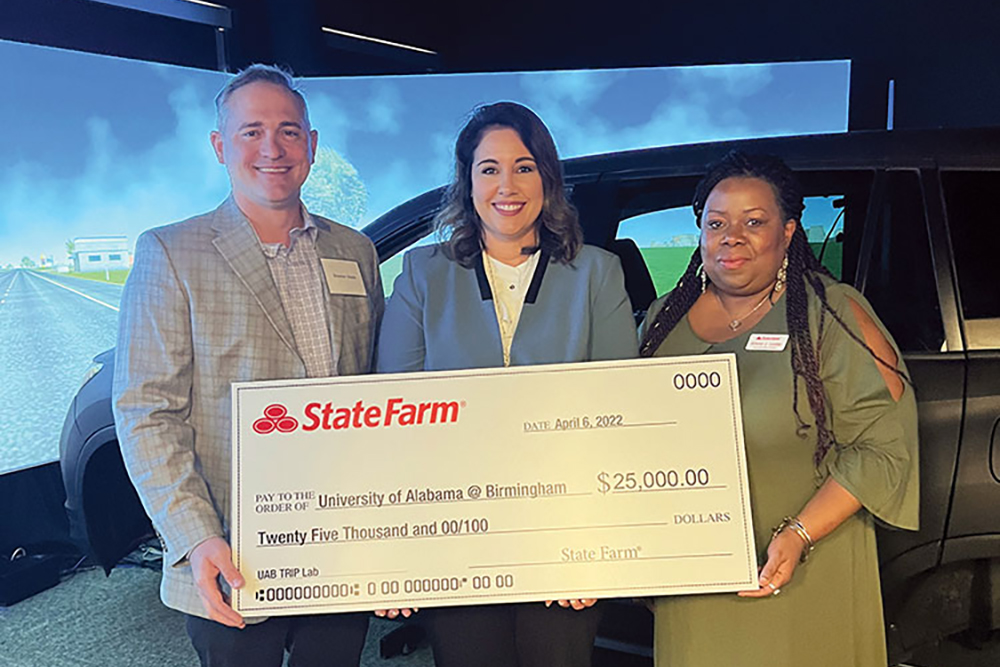

Braxton Wade, State Farm Sales Leader, and Arlene Lester, State Farm Corporate Responsibility Analyst, present a generous donation to the TRIP Lab.In addition to providing valuable research data, the simulator also enables teenagers to experience dangerous driving situations while operating in a secure environment, rather than out on the open road. In an attempt to reach as many high schoolers as possible, the TRIP Lab regularly takes a portable simulator to the Birmingham City Schools and works with students in driver’s ed classes.

Braxton Wade, State Farm Sales Leader, and Arlene Lester, State Farm Corporate Responsibility Analyst, present a generous donation to the TRIP Lab.In addition to providing valuable research data, the simulator also enables teenagers to experience dangerous driving situations while operating in a secure environment, rather than out on the open road. In an attempt to reach as many high schoolers as possible, the TRIP Lab regularly takes a portable simulator to the Birmingham City Schools and works with students in driver’s ed classes.

“It has helped the students feel more confident about driving,” said Sherri Huff, program specialist in physical education, health, and driver’s ed for Birmingham City Schools. “I hear comments all the time from students that they are apprehensive about getting their license. But if they can get some experience through the simulator, they feel less threatened about driving a motor vehicle.”

“It’s fantastic that they have this opportunity to work with UAB to learn better driving skills and be more equipped with safety measures. I’m very grateful that we have this partnership. It’s made a world of difference for students who don’t feel as confident about driving. It’s helped them tremendously.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic prevented in-person interaction with the schools, the TRIP Lab team created a virtual version of the program for young drivers available through Zoom sessions and YouTube videos. The Regional Planning Commission of Greater Birmingham (RPCGB) supported that program through a generous grant.

Now, State Farm has joined RPCGB in helping to expand the distracted driving outreach program with a new grant that will enable the TRIP Lab to take the portable simulator to high schools throughout the state.

“Helping people recover from the unexpected and realize their dreams is a part of our daily mission,” said Arlene Lester, corporate responsibility analyst at State Farm. “However, preventing the unexpected through education is also at the forefront of our mind. The UAB TRIP Lab aids in creating safer and more educated communities.”

“I am impressed at the level of detail displayed in their research, and how they bring the research alive through their interaction with the students. The program emboldens students to listen, and then moves them to action as they learn about ways to engage on the road. They have made a remarkable difference in how teens accept their responsibility while driving, or even as a passenger. It is our honor to provide resources to promote their work across Alabama.”

Research Opportunities for UAB Students

But it is not only high school students who are benefitting from the TRIP Lab. Stavrinos says more than 150 UAB students have worked in the lab as research assistants over the years.

“From the beginning we’ve prioritized having students in the lab, and we allow them to really get involved,” said Stavrinos. “Students come in and engage in research depending upon where we are in our project. They develop protocols, work on data collection and data analysis. They can jump in at any stage of research. We want them to be integrated into the lab as fully as possible and have an opportunity to learn firsthand how research happens.”

“I’m a very applied researcher, and much of the work we do at UAB is addressing real-world problems.” — Despina Stavrinos, Ph.D.

“Oftentimes this is the first place they’ve ever participated in research. I had the opportunity to do that as an undergrad, and that’s what made me realize I wanted to do this as a career. So, I want to give undergrads that same opportunity to get into a lab and actually help design and run studies, analyze findings, and translate that to the community in terms of safety.”

While the majority of the research assistants have come from the Department of Psychology, Stavrinos says the lab has welcomed students from a wide variety of disciplines, including engineering, nursing, medicine, public health, and education. “Transportation is a complex issue, so there are a lot of different perspectives on it,” said Stavrinos.

Rachael George, a junior majoring in public health, began working in the TRIP Lab last year. She admits she was a bit hesitant at first since the lab operates under the umbrella of psychology.

Ramsay High School students participating in TRIP Lab's distracted driving outreach program."When I first heard about the TRIP Lab, I thought it was kind of strange that they were studying cars in a psychology lab,” said George. “But I talked with some people who recommended it, and then heard a lecture from (Stavrinos) that made me interested in applying.”

Ramsay High School students participating in TRIP Lab's distracted driving outreach program."When I first heard about the TRIP Lab, I thought it was kind of strange that they were studying cars in a psychology lab,” said George. “But I talked with some people who recommended it, and then heard a lecture from (Stavrinos) that made me interested in applying.”

“It’s the right fit for me because it not only has the dedication to research, it also has the strong dedication to the translation aspect of going back into the community. I also really liked seeing some of the computer science stuff that happens. It’s just been a really great chance to get involved in research on campus, and to do more than just one thing at a research lab.”

One way George has assisted with TRIP Lab’s outreach is by working to bulk up the lab’s various social media platforms. Over the past year, she says the lab’s follower count has doubled on both Instagram and Facebook—also, the lab recently established a new presence on TikTok.

“I wanted to try to turn our social media into a way to reach students and other people who may be able to participate in the studies we’re running,” said George. “A lot of people are getting a chance to see the research process for the first time, and they didn’t realize how accessible it can be if they want to participate in a research lab or a study.”

The Road Ahead

Moving forward, Stavrinos expects the TRIP Lab to do more research work in areas beyond teenage driving. She said that has already happened, as the lab has been approached by several other schools and departments throughout UAB.

“Because we can customize our simulator scenarios, it has opened up so many research opportunities,” said Stavrinos. “The scientific community at UAB is asking about it. It’s branched into work involving medical patients. Clinicians want to know, ‘Can my patient drive safely with a certain condition, or after a certain medical procedure?’ So, we’ve branched out beyond just teen driver work, because we’re realizing that there are so many applications.”

For example, the TRIP Lab has started a new project in collaboration with Nationwide Children’s Hospital and Ohio State University involving patients who are recovering from brain injuries, including concussions.

For example, the TRIP Lab has started a new project in collaboration with Nationwide Children’s Hospital and Ohio State University involving patients who are recovering from brain injuries, including concussions.

“There are currently no guidelines on when somebody can return to driving after a concussion,” said Stavrinos. “Doctors base it on how you feel, but they’d rather have some objective data. Here, the simulator plays a really important role. The sim offers a very controlled, safe way to test what their capabilities look like.”

Other research possibilities include changes in vision for night-time driving, the ability to drive following a hip procedure or leg/angle fracture, and returning to driving after a stroke. The SUV simulator even was utilized by a graduate student conducting a project involving parents properly using booster seats for infants. “The scenarios can be customized around the fundamental research question,” said Stavrinos.

Those questions and scenarios likely will continue to change right along with technology. McManus points out that when the lab first started, the primary cause of driver distraction was texting on a cell phone. Now, new technologies have created new distractions—such as people using smart watches while driving.

“The technology keeps changing, so the research has to keep moving with it,” said McManus. “That’s one of the things this lab has been able to do, is see the challenges in the future and move with them, both with our technology but also through research, education, and community engagement through outreach.”

“That’s one of the strengths of the lab. We are able to adapt and keep moving.” As a result, drivers are able to keep moving as well. And to do so more safely.