|

Gorgas Case 2014-09 |

|

| Diagnosis: Dengue. |

|

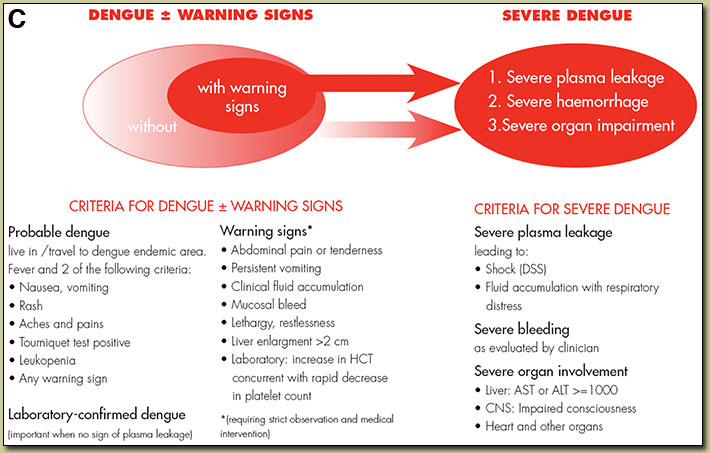

In acute dengue, virus may be isolated from blood; PCR of blood will be positive, or NS1 antigen may be detected in the blood during the first 5 days only. IgM elevations do not occur until 5 days or more, so a sample taken earlier may be negative. Four-fold elevations of IgG on acute and convalescent serum may be required to confirm diagnosis. Dengue infections range from asymptomatic through a range of clinical manifestations to death. The incubation period of this flavivirus is normally 3–7 days from the time of the infective bite of the Aedes mosquito and 14 days at the most. After the incubation period, the illness begins abruptly and is followed by the three phases – febrile, critical and recovery. Typical dengue fever is manifest by frontal headache, retro-orbital pain, muscle and joint pain, nausea, vomiting and rash. The febrile phase lasts 2–7 days. Malaria, other arboviruses, leptospirosis, rickettsial disease, measles, rubella, or typhoid may present similar findings in the pre-rash phase of infection and need to be tested for. Mild elevations of liver function tests are typical of dengue as well as the other diseases mentioned. The morbilliform rash is similar to that found in rubella, which needs to be considered in inadequately immunized patients. If symptoms begin more than 2 weeks after a patient has left an endemic area dengue can be essentially ruled out. When the temperature drops to 37.5–38.0ºC or less and remains below this level – usually on days 3–7 of illness – an increase in capillary permeability in parallel with increasing hematocrit levels may occur, and marks the beginning of the critical phase when it occurs (though not in this case) [see Gorgas Case 2011-09 for an example]. This period of clinically significant plasma leakage usually lasts 24–48 hours. Plasma leakage, hemoconcentration and abnormalities in homeostasis characterize severe dengue when it occurs. The mechanisms leading to severe illness are not well defined but the immune response, the genetic background of the individual and the virus characteristics may all contribute to severe dengue. Mild bleeding such as epistaxis or mucosal bleeding by itself is not enough to classify a patient as severe dengue. Increasingly, small pleural effusions are recognized in dengue by ultrasound but are not indicative of severe plasma leakage unless there is respiratory compromise. Primary infection by any of the four virus serotypes (DEN 1-4) is thought to induce lifelong protective immunity to the infecting serotype. Sero-epidemiological studies in Cuba and Thailand consistently support the role of secondary heterotypic infection (with another serotype) as a risk factor for severe dengue, although there are a number of reports of severe cases associated with primary infection, which may be a reflection of viral virulence factors. Dengue was reported in Perú for the first time in 1990; since then, all four serotypes are circulating, mainly along the north coast and the jungle. In 2014, DEN-2 has been predominant in the Iquitos area; it was isolated in 2011 for the first time and appears to be persisting. Perú reports approximately 10-20,000 dengue cases per year, mostly from Loreto and Ucayali. 25% of cases have warning signs and 1% meet WHO criteria for severe dengue [see Image C ]. Treatment of dengue is supportive with hydration and observation for severe sequelae such as DIC, overt plasma leakage and shock. Our patient had persistent vomiting and abdominal pain – two of the Warning Signs. |

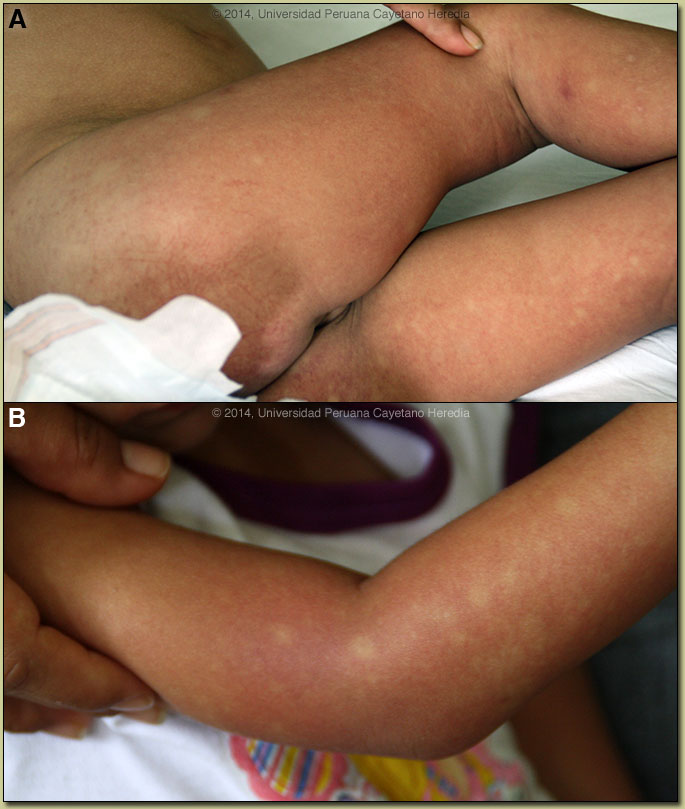

Discussion: Malaria thick smear was negative. PCR and NS1 test results were pending at the time of our assessment but the classic morbilliform rash [see Images A & B], often described as white islands on a red sea was present [see also

Discussion: Malaria thick smear was negative. PCR and NS1 test results were pending at the time of our assessment but the classic morbilliform rash [see Images A & B], often described as white islands on a red sea was present [see also