Lynda Welker has led a full life despite her heart defect thanks to James Kirklin.Lynda Welker is a woman who has experienced a multitude of peaks and valleys in her 51 years of life.

Lynda Welker has led a full life despite her heart defect thanks to James Kirklin.Lynda Welker is a woman who has experienced a multitude of peaks and valleys in her 51 years of life.

When she was 15 years old, she underwent her first heart surgery because her heart developed only a single ventricle at birth. Children with this defect are born with hearts that have only one ventricle large enough or strong enough to pump effectively.

Welker slowly grew to 70 pounds as a teenager, but her skin was also growing more blue — a sign her blood lacked oxygen.

“I was always blue,” Welker said. “I looked like a toddler going into kindergarten.”

Doctors told her at 15 she would become bedridden in six months.

Welker was referred to the University of Alabama at Birmingham by her doctors in North Carolina and was examined by the late John Kirklin, M.D., who recommended she undergo a septation procedure.

Patients with certain types of single ventricle defects have one large ventricular chamber without any division; but aligning the valves and the valve support structure allows for placing an artificial patch to divide the single ventricle into a physiological right and left ventricle, thus creating two ventricles as in a normal heart.

Because of the complexity of this operation and significant early mortality in the 1980s, this procedure was abandoned by most congenital heart centers in favor of the simpler and more predictable Fontan procedure.

The Fontan procedure,in which blood circulation is divided normally between the heart and lungs, does not include a pumping chamber to propel blood into the lungs, and the long-term outcome beyond 20 years is uncertain. Fontan patients, because of the absence of a pumping chamber to the lungs, do experience chronic congestion of the liver and occasionally right-sided heart failure.

On Oct. 26, 1981, Kirklin and his son, James Kirklin, M.D., performed the procedure together on Welker. In the early 1980s, this procedure carried a 10-15 percent risk of hospital mortality. Additional risks include a high likelihood of heart block requiring a pacemaker, and the possibility of progressively leaking valves that could require implantation of an artificial valve.

From left: Stacy Brooks, Lynda Welker, Kathy ClayWelker did suffer heart block and has required a pacemaker since that time. She has had her pacemaker replaced four times by James Kirklin.

From left: Stacy Brooks, Lynda Welker, Kathy ClayWelker did suffer heart block and has required a pacemaker since that time. She has had her pacemaker replaced four times by James Kirklin.

“Lynda had an excellent early result from her septation procedure, despite requiring a pacemaker and subsequently a valve replacement,” he said. “The function of her two ventricles has been excellent over the years, and Lynda has done a superb job of managing her own personal health.”

Welker, a native of McLeansville, North Carolina, says she would never have made it this far without a strong support system of family members, nurses and even strangers. Just a few years after her initial surgery and one pacemaker replacement, Welker was able to walk across the stage at her high school graduation.

“Everyone stood up and cheered for me when I walked across that stage,” Welker said.

Stacy Brooks, Welker’s childhood friend, accompanies her to most of her appointments. The Gardendale, Alabama, native has the utmost respect for her friend. Brooks’ grandson has suffered from heart defects, but uses Welker as an inspiration and guide to help get through tough times.

“She’s a very strong person to endure what she’s been through,” Brooks said. “She was told that she would live to be 12, and now she’s well past that.”

Brooks’ grandparents offered to share their home when Welker first came to Birmingham for her consultation with Kirklin. Brooks’ family continues to provide a place to stay and transportation for Welker when she visits UAB.

Welker also attends First Gardendale Baptist Church when she stays in Birmingham.

“I’ve had people from all over tell me they’ve been praying for me,” she said.

Welker’s original UAB nurse from 1981, Kathy Clay, tries to make a few trips to Birmingham when Welker comes for doctor visits.

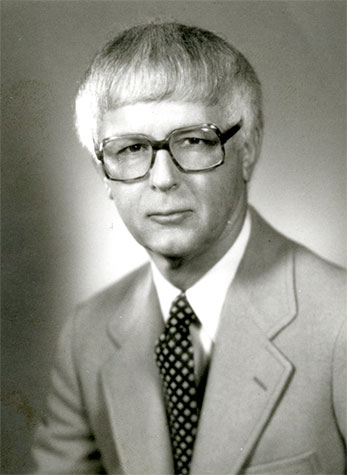

John Kirklin (Photo credit, UAB Archives)“We’ve been friends ever since,” Clay said. “I remember Dr. (James) Kirklin was just a resident at that time. It’s been amazing to see Lynda grow and have a great life.”

John Kirklin (Photo credit, UAB Archives)“We’ve been friends ever since,” Clay said. “I remember Dr. (James) Kirklin was just a resident at that time. It’s been amazing to see Lynda grow and have a great life.”

Welker says her aunt and uncle, Linda and Barry Kluttz, and caseworker Valerie Holley were also very instrumental in providing constant support throughout the entire process.

“Valerie and I bonded so well,” she said. “She was an inspiration to me.”

After almost 35 years, three pacemaker changes and suffering from a lightning strike, Welker returned to UAB Hospital and The Kirklin Clinic for a fourth pacemaker change in March 2016. As she walked along the hallways, she was reminded about attending the ribbon cutting for The Kirklin Clinic’s grand opening.

Welker is thankful for the surgery because she has been able to live a full life. She worked for the Guilford County School System in North Carolina for a number of years in the exceptional children department. She also has traveled across the country and abroad.

To her, the Kirklins are more than renowned surgeons and a name on a building.

“I think the world of them,” she said. “They treated me not just as a patient, but as if they cared for me and loved me. I felt they were part of my family. They changed my life.”

One of the ways Welker wants the Kirklin family to always be remembered is through her 19-year-old son, whom she named Jeremy Kirklin Harville. She wanted her son to have the same initials as John and James Kirklin.

“Of course, this a tremendous honor for my father and for me, given the wonderful outcome that Lynda has enjoyed, her lifelong bond with UAB and the cardiovascular physicians here, and her commitment to help others suffering from heart disease,” Kirklin said. “Most of all, I am thrilled to see Lynda enjoying such good health, an active and healthy lifestyle, and reaping the benefits of a wonderful family. She is a true champion of the victories that routinely occur today in the battle against otherwise fatal congenital heart malformations.”

Welker hopes to start a nonprofit organization, Kirklin Heartbeats, with proceeds going to cardiovascular research at UAB. She feels that, with advances in technology and increased awareness, children with similar heart defects also can enjoy long and full lives.