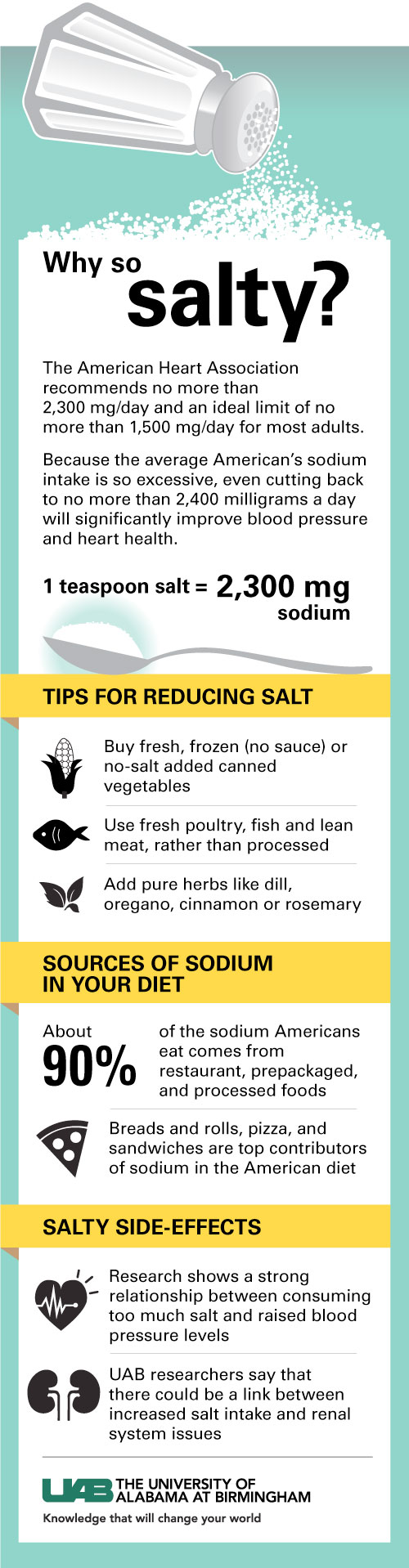

Sodium intake continues to be a major issue for many Americans. While the American Heart Association recommends an ideal limit of no more than 1,500 mg per day for most adults, recent findings showed that, from 2013-2014, the average daily U.S. sodium intake was 3,409 mg — excluding salt added at the table.

Approximate amounts of sodium in a given amount of table salt:

|

The AHA recommends no more than 2,300 milligrams a day, and an ideal limit of 1,500 mg for most adults.

“Most items you buy at the grocery have a food label that will tell you exactly how much sodium is in that product,” Threadcraft said. “The recommended daily sodium intake is 2300 mg or less, which may seem like a lot, but that’s really the equivalent of a teaspoon. It is very easy to overconsume without realizing it.”

She says most Americans consume their recommended sodium intake already through the foods they eat day to day, and when people add more salt for flavor, that pushes them over the limit.

Because the average American’s sodium intake is so excessive, even cutting back to no more than 2,400 milligrams a day will significantly improve blood pressure and heart health.

“I encourage people to taste their food before salting to see if food actually needs it to ensure they’re not salting simply out of habit,” she said.

Read the labels

Americans get most of their daily sodium — more than 75 percent — from processed and restaurant foods. Sodium is already in processed and restaurant foods when purchased, which makes it difficult to reduce daily sodium intake.

“I think the first and most important thing people can do is to read the labels on the products they buy,” Threadcraft said. “Pre-packaged foods definitely have their place, but they should be chosen carefully.”

“I think the first and most important thing people can do is to read the labels on the products they buy,” Threadcraft said. “Pre-packaged foods definitely have their place, but they should be chosen carefully.”

She noted that the first thing to do when looking at labels is to identify the serving size, then look at the milligrams of sodium which are connected with the serving size listed.

“A lot of people who have busy schedules need something quick and pre-prepared to eat,” she said. “That doesn’t mean you have to give up flavor in order to get something healthy that is also easy to make. Frozen vegetables are a great option for a quick and low-sodium side at dinner, and typically there is no sodium added.”

Threadcraft says, when using canned vegetables, look for low-sodium or sodium-free options since many canned food items are high in sodium. Rinsing canned items is another way to reduce the sodium content.

According to the CDC, Americans eat at fast food or dine-in restaurants four or five times a week. For those who frequent restaurants, Threadcraft says most establishments have their nutrition facts listed either online or in the store.

Flavor fresh

Threadcraft says consumers should be aware of hidden sources of sodium such as sauces and dressings, and ask for these toppings on the side. One tablespoon of teriyaki sauce can have 879 milligrams of sodium. The same amount of soy sauce may have up to 1,005 milligrams — almost half of the recommended daily intake.

Threadcraft suggests using pure herbs and spices instead of extra salt to find the perfect flavor.

“There is no salt in pure herbs and spices at all, and you can get a very rich flavor from those,” she said. “Acidic juices like orange or pineapple are great marinade alternatives for chicken or fish compared to barbecue sauce or soy sauce.”

To get the most flavor from herbs, crush or rub them before adding them to the dish. Buy herbs and spices in small amounts as you need them rather than storing them for a long time. If using fresh herbs such as parsley or cilantro, store them in water so they stay fresh.

All foods can fit

Most Americans eat three meals a day, and depending on diets, breakfast may be the biggest culprit when it comes to sodium intake.

“In the South, we love our salt,” Threadcraft said. “Breakfast casseroles, sausage and bacon are major sources of sodium.”

She says that, while watching sodium intake can be tedious, all foods can fit.

“If you really love bacon, which is high in sodium, then maybe you can make a wise choice and not add salt to your eggs at breakfast,” she said. “You can find ways to compromise, but be smart with it.”

Health risks

“Excess sodium can increase your blood pressure and your risk for a heart disease and stroke,” Threadcraft said. “Together, heart disease and stroke kill more Americans each year than any other cause.”

But salt does not just increase risk of stroke and heart disease. UAB researchers David and Jennifer Pollock, Ph.D., are studying the effects of salt on the renal system.

“We know that the Western diet we all eat has far too much salt in it, and we know the number of people consuming salt in Western and developing countries is rising,” David Pollock said. “Evolutionarily speaking, we didn’t have bountiful salt in the diet until just in the last 100 years. But physiologically, we are designed to conserve salt. We haven’t evolved to handle these high-salt diets we’re eating. Now that it’s become appreciated that a high-salt diet may contribute to the rise of many diverse health problems including autoimmune disease, trying to understand how the body regulates salt is extremely important.”

Threadcraft says that salt is not inherently bad, but people need to learn to manage it effectively. Salt helps to maintain the body’s fluid balance and maintain muscle contraction and is a vital component of blood, plasma and digestive secretions.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has released draft, voluntary sodium reduction targets for processed and prepared foods. This new guidance lays out achievable short-term and long-term goals for sodium reduction in about 150 categories of food.