CPM groundbreaking ceremony, 1989. Photo provided by UAB Archives.On Sept. 27, 1989, the University of Alabama at Birmingham broke ground for a new building. The Center for Psychiatric Medicine, as the edifice on Sixth Avenue South was to be called, would be a game changer for mental health in Alabama.

CPM groundbreaking ceremony, 1989. Photo provided by UAB Archives.On Sept. 27, 1989, the University of Alabama at Birmingham broke ground for a new building. The Center for Psychiatric Medicine, as the edifice on Sixth Avenue South was to be called, would be a game changer for mental health in Alabama.

“There was increased recognition at that time that the way we treated mental illness needed to be changed,” said Will Ferniany, Ph.D., CEO of UAB Medicine. Ferniany was a junior administrator at UAB in 1989, and was charged with overseeing the construction of the CPM. “The CPM was designed to be a top psychiatric facility, one that would appeal to patients and meet the growing need for mental health services.”

“When the CPM was opened in 1992 — 25 years ago — the state of mental health care was changing,” said James Meador-Woodruff, M.D., professor and chair of the UAB Department of Psychiatry. “The old model had seen many patients with psychiatric disorders placed in state hospitals. Treatment options were limited, and often ineffective. In the early 1990s, we began a shift to community-based treatment, utilizing outpatient settings to keep patients engaged in their communities and out of the hospital.”

James Meador-Woodruff, M.D.Meador-Woodruff, who holds the Heman E. Drummond Endowed Chair of Psychiatry, calls that effort a noble idea, one which went a long way to destigmatize mental illness and provide successful therapy outside of a hospital setting.

James Meador-Woodruff, M.D.Meador-Woodruff, who holds the Heman E. Drummond Endowed Chair of Psychiatry, calls that effort a noble idea, one which went a long way to destigmatize mental illness and provide successful therapy outside of a hospital setting.

“But we went too far,” he said. “Now we have only two state mental health hospitals in Alabama and a backlog of patients who would benefit from inpatient treatment. Over the years, the CPM has played an integral role in balancing inpatient and outpatient therapy, offering inpatient care coupled with successful, community-based outpatient therapy.”

The Center for Psychiatric Medicine operates 94 inpatient hospital beds for adolescent, adult and geriatric patients. It also features outpatient clinics, including an addiction recovery program. More than 51,000 people have been patients of the facility over the years. Fourteen faculty psychiatrists, as well as nearly 40 psychiatry residents and fellows, see patients in the facility.

“One of the strengths of the CPM is that it can provide a continuum of care with outpatient, inpatient and partial hospitalization programs,” said Elizabeth Caine, the administrative director for the CPM.

Lengths of stay for psychiatric inpatients used to be measured in weeks or months. Now, Caine and Meador-Woodruff say the average inpatient visit lasts just six days.

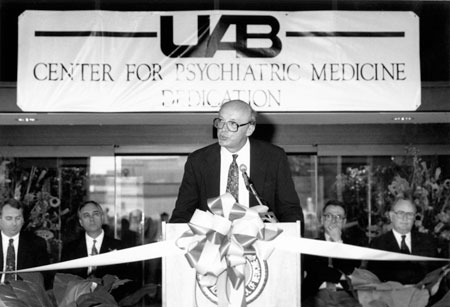

CPM dedication, 1992. Photo provided by UAB Archives.“That means more availability for inpatient beds, and we can treat more people, especially when coupled with outpatient therapy,” Caine said.

CPM dedication, 1992. Photo provided by UAB Archives.“That means more availability for inpatient beds, and we can treat more people, especially when coupled with outpatient therapy,” Caine said.

And outpatient therapy in mental health has been driven by advances in medications.

“The CPM came on the scene about the same time two medications entered the market that had a profound effect on how we treat mental illness,” Meador-Woodruff said. “Prozac, the first of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, received FDA approval in 1987. These new SSRI medications were dramatically different. They had fewer side effects, were easy to take and were effective. They kept people out of hospitals.”

Another drug, called clozapine, became available for the treatment of schizophrenia. Developed in Europe in the 1970s, clozapine gained FDA approval in 2002 in the United States.

From patient to provider: One man’s journey through the CPMIn his royal blue scrubs, Ryan Kielbasa looks like any other employee at UAB’s Center for Psychiatric Medicine. He’s a patient care technician in the Addiction Recovery Unit. But he’s much more to the patients on that unit. He’s part confidant, part mentor and part conscience. Because he’s been there himself.

“Addiction is a vicious cycle, and until you break the cycle you don’t have a chance to get better,” said Kielbasa. “You have to hit a personal rock bottom, when you reach a point where you make the decision that you are willing to do what it takes to change. The only thing I had to change… was everything. I have a disease which centers in the mind. I began acting my way into better thinking, rather than trying to think my way into better acting. I do not let the past define who I am, however, it is my past which has let me to where I am today.” The turning point came when he ended up the high acuity psychiatric unit at the CPM in 2013. He says a seed was planted during that stay. It took another relapse and one more hospitalization for the seed to mature. “It was a seed of hope that I could change my behavior,” Kielbasa said. “I had a moment of clarity where I could see the potential of living a sober life. It took two more years, but I got there. My sobriety date is June 1, 2015, the last time I used any substances.” Once clean, Kielbasa managed a sober living community before joining UAB. Having already earned a degree in psychology in 2006, he’s now working on a Masters degree in clinical medical social work. In addition to his formal duties on the Addiction Recovery Unit, Kielbasa shares his own experiences — and his recovery — with his patients. “I can break some of the walls that patients put up because I’ve been where they are and I’ve lived that life,” he said. “I’m in recovery as well, and hearing my story helps create an element of trust.” Once he finishes his Master’s degree, Kielbasa hopes to remain in social work at UAB, with an emphasis on dual diagnosis of mental illness coupled with addiction. “Because of my story, I can help people get to an honest place, one where therapy can begin and recovery can be possible,” he said. “I love this. I love this work.” |

“Clozapine is one of the reasons the need for psychiatric beds in state hospitals dropped as it did,” Meador-Woodruff said. “It transformed psychiatry, as it helped those with schizophrenia to live normal lives, and to live within the community. So, we saw two prototype medications come on the market during this time period that have transformed how we treat serious psychiatric disorders.”

Meador-Woodruff also singles out Prozac and the other SSRIs that followed for playing a major role in lessening the stigma of mental illness.

“You’ll recall the term ‘Prozac Nation,’ which arose as SSRIs became culturally acceptable,” he said. “The stigma associated with mental health care dropped markedly. It is now estimated that somewhere between 15 and 24 percent of the U.S. population use some sort of mental health medication.”

The new scourge facing the mental health community is addiction, in particular opioid addiction. The CPM is home to the UAB Addiction Recovery Unit, a 16-bed inpatient unit for those coping with addiction.

“We refer to the unit as a place for recovery stabilization,” Caine said. “It provides a supportive community that combines inpatient care with intensive outpatient as well as after-care programs.”

“Twenty-five years ago, those addicted to drugs often went to jail,” Meador-Woodruff said. “Now we recognize drug abuse is a public health problem and a condition that can be treated.”

The center’s Addiction Recovery program responded to the opioid crisis by expanding services, adding five beds in 2017. Patients enroll in a 90-day therapy program, inpatient the first month and then transitioning to outpatient programs for the final two months.

Patients take part in group and individual therapy, including family sessions and psychological and psychiatric evaluations as needed. There also is a follow-up care plan to assist patients after the initial treatment.

“New medications such as suboxone and naloxone are helping treat addiction,” Caine said. “Programs like UAB Hospital’s Addiction Scholars Program, which trains medical professionals to recognize and treat underlying addiction issues in patients throughout the hospital, can also have an effect on the situation. One major hurdle that remains is ending the stigma associated with opioid addiction.”

Another hurdle facing psychiatry in general is a shortage of psychiatrists. Among medical disciplines, only primary care is facing as acute a shortage as psychiatry.

“At the time the CPM was built, some 10 percent of medical school graduates went into psychiatry, but that number has dropped to around 3 percent in recent years,” Meador-Woodruff said. “The trend is beginning to reverse. Five years ago, 40 percent of residency spots in psychiatry were unfilled. Last year, there were only six positions in the entire country that were not filled. Coupled with the increased use of advanced practice nursing, we are getting closer to ending the imbalance.”

Meador-Woodruff and Ferniany agree that the mental health care system needs support, funding and resources.

“We need more services for mental health, not necessarily more beds but more therapeutic services,” Ferniany said. “We need the state to take on the role of leading mental health care in Alabama.

“We are in transition,” Meador-Woodruff said. “The stigma of mental illness will continue to decrease. Advocacy will increase. Hopefully, we will get to the right distribution of resources. We’ll take the research from the decade of the brain and find the next generation of medications that will be more effective with fewer side effects. Precision medicine will play a role, as will telemedicine. It is an exciting time.”

And an exciting milestone for the UAB Center for Psychiatric Medicine, as it celebrates the past 25 years and looks forward to the next quarter-century.

The CPM will host an anniversary reception at 4 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 13, at the center, 1713 Sixth Ave. South, Birmingham.