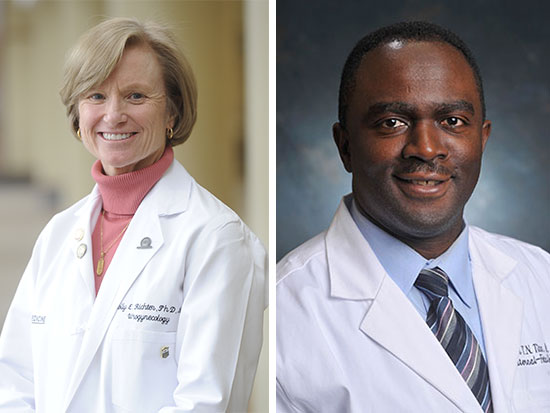

Holly Richter, left and Alan TitaA multicenter study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association involving more than 2,400 first-time pregnant women shows that the timing of pushing during labor has no effect on whether women deliver vaginally or by cesarean section. However, the findings do indicate that delayed pushing led to longer labors and higher risks of severe postpartum bleeding and infections, and those babies were more likely to develop sepsis.

Holly Richter, left and Alan TitaA multicenter study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association involving more than 2,400 first-time pregnant women shows that the timing of pushing during labor has no effect on whether women deliver vaginally or by cesarean section. However, the findings do indicate that delayed pushing led to longer labors and higher risks of severe postpartum bleeding and infections, and those babies were more likely to develop sepsis.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham was one of the study’s six sites through the Center for Women’s Reproductive Health (CWRH) and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis served as the study’s lead site.

While many obstetric providers recommend that a woman begins pushing as soon the cervix is fully dilated, others advise waiting until she feels the urge to push; until now, doctors have not had conclusive evidence about which approach is better for mothers and their babies. Women also have varied preferences regarding the timing of delivery.

“These findings represent a crucial contribution to the body of information available to guide women, their providers and policymakers about what timing of pushing is better for mom and baby,” said Alan Tita, M.D., Ph.D., professor in UAB’s Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, director of the CWRH, and an author of the study.

The study enrolled 2,414 first-time pregnant women across the six U.S. hospitals between May 2014 and November 2017. Women were at least 37 weeks’ pregnant with a single baby, and all had received epidural anesthesia to reduce labor pain. Once the cervix was fully dilated at 10 centimeters, indicating the beginning of the second stage of labor, the women were randomly assigned either to begin pushing immediately or to delay pushing for 60 minutes. Findings included:

- Of those in the immediate-pushing group, 1,031 (85.9 percent) delivered vaginally compared with 1,041 (86.5 percent) in the delayed-pushing group — a difference that is not clinically or statistically significant.

- Women in the immediate-pushing group experienced significantly lower rates of infection and fewer episodes of excessive bleeding following delivery. Specifically, 80 (6.7 percent) of the women who began pushing immediately developed an infection compared with 110 women (9.1 percent) who delayed pushing.

- In addition, 27 (2.3 percent) in the immediate-pushing group suffered severe postpartum bleeding (a major cause of maternal death), compared with 48 (4 percent) in the delayed-pushing group.

- Additionally, women who pushed immediately experienced a shorter second-stage of labor by an average of 30 minutes, compared with those who delayed pushing — 102.4 versus 134.2 minutes.

“Another important aim of the trial was to determine whether the type of pushing affects the mother’s health in the longer term, including outcomes such as urinary and bowel incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse,” said Holly E. Richter, M.D., Ph.D., professor in the UAB Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, a co-author of the study and the primary investigator for the pelvic floor outcomes component. “This research endeavor is a model for successful multidisciplinary collaboration within departments and across institutions, and we are eager to continue to learn more about how to better manage labor for moms and babies, both in the short and long terms.”

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health.