In his new book, Jonathan Wiesen, Ph.D., professor in the Department of History, highlights the current understanding of the “tension between coercion and consensus” in the Nazi period, he said.Everyone knows the rough outline of Nazi Germany: Adolf Hitler seizes power in the 1930s in a military coup, brainwashes the German people with a mix of psychological tricks and occult imagery, and then immediately implements his long-held plan to exterminate European Jews.

In his new book, Jonathan Wiesen, Ph.D., professor in the Department of History, highlights the current understanding of the “tension between coercion and consensus” in the Nazi period, he said.Everyone knows the rough outline of Nazi Germany: Adolf Hitler seizes power in the 1930s in a military coup, brainwashes the German people with a mix of psychological tricks and occult imagery, and then immediately implements his long-held plan to exterminate European Jews.

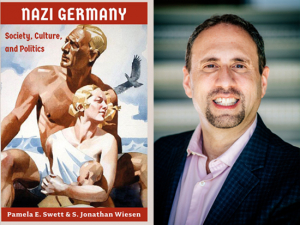

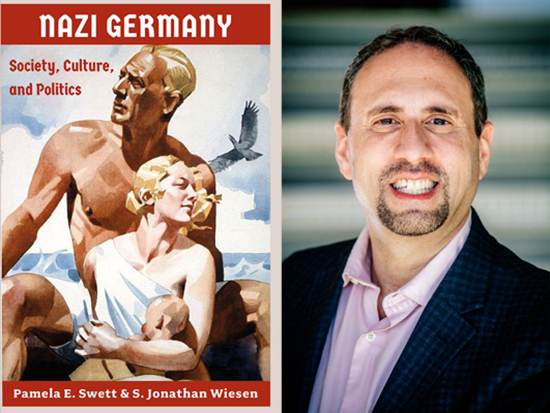

Except “none of that is true,” writes Jonathan Wiesen, Ph.D., professor and past chair of UAB’s Department of History in “Nazi Germany: Society, Culture and Politics,” a new book from Bloomsbury Press.

“This textbook seeks to challenge such myths that surround the period in German history, sometimes known as the ‘Third Reich,’” Wiesen and his co-author Pamela Swett, historian at McMaster University in Canada, write.

“There is a lot more going on in this 12-year period, although none of it is that happy unless you were considered racially ‘pure,’” Wiesen said. “Germany under the Nazis was a modern society, very dynamic, but combined with very reactionary attitudes.” In addition to a thorough overview of the rise of National Socialism, the book examines the German economy and society during those years, racism and the treatment of gender and sexuality, arts and culture, the regime’s relations to the outside world, the upheavals of the war years, and the Holocaust, among other topics. Color plates reproduce the often-striking artwork that promoted the Nazi regime in posters and advertisements.

Inside a “consensus dictatorship”

“Nazi Germany” highlights the current understanding, which has been slow to appear in textbooks, of the “tension between coercion and consensus” in the Nazi period, Wiesen said. “We rightly think of Germany as a police state. But it’s interesting to see how many people looked back at that period and — if they weren’t a racial minority or otherwise part of an ‘undesirable’ group — said, ‘Those were good years,’” Wiesen said.

“On the ground, the average German experienced Hitler much differently than we might expect,” Wiesen said. “We might call it a consensus dictatorship.”

The book grew out of a project led by the German Historical Institute, which asked Wiesen and Swett to update its online collection of Nazi documents and recordings “to reflect our latest understanding of Nazi Germany,” Wiesen said. From there, the co-authors, who had previously edited a book on advertising in 20th century Germany, decided it was time for a new textbook.

The fact that the Nazis relied on unique levels of violence obscures another reality that Wiesen and Swett highlight in their book: Germany, before the war, “was part of a large, transnational network,” Wiesen said. “It was not secluded in any way. Despite its many crimes, it tried to present itself as a normal nation, and a lot of tourists came to Germany to see what Hitler and the Nazis had achieved.”

Nazis visit the South

At the same time, the Nazis were studying other nations, including the bureaucratic underpinnings of Jim Crow laws in the American South and other racial discrimination in the United States. In 2017, Wiesen wrote an academic paper about this, titled “American Lynching in the Nazi Imagination: Race and Extra-Legal Violence in 1930s Germany.” Wiesen highlighted the activities of a German law student from Dusseldorf named Heinrich Krieger, who studied at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville in 1934. Krieger was exploring “Southerners’ treatment of African Americans, Native Americans, and Asians,” Wiesen writes. “And alongside his regular coursework, he met with professors and politicians to discuss the minutiae of segregation.”

Writer Malcolm Gladwell recently devoted part of an episode of his podcast “Revisionist History” to Krieger, as part of a series on the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. In his research, Gladwell came across Wiesen’s article and reached out to the historian for an interview. A short segment of their discussion is included in the podcast.

(This is not the first time Gladwell has been intrigued by the work of UAB faculty. Gladwell’s book “Talking to Strangers” draws on the work of Timothy Levine, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor in the Department of Communication Studies, and was instrumental in Gladwell’s visit to the Alys Stephens Center in October 2019.)

Wiesen noted that faculty at several universities have already begun assigning “Nazi Germany” for their courses. “We intended it for undergraduates, graduates and the general public, as well,” he said.

Germany and the American color line

Wiesen is now almost done with his next book, “Modern Germany and the American Color Line,” which expands on his 2017 article. “It is about how Germans have understood racism in America, particularly anti-Black racism,” he said. The Nazis were eager to denounce lynchings and other violence against African Americans, especially as boycotts and other protests against Nazi terror gained strength in the United States in the 1930s. But Krieger and other Nazi true believers, contrary to what one might expect, actually disapproved of these activities. “You would think they would support the lynching of racial minorities, but they condemned it as ‘wild west American violence,’” Wiesen said. “Sometimes they identified with American racists, but not always.”

Wiesen also is researching a project on the German-American agent George Sylvester Viereck, who “was an active publisher against American involvement in World War I and in World War II was a paid agent for Germany in America,” Wiesen said. He has also been working on and off for the past 20 years on a project looking at the myth that Hitler himself had Jewish heritage. “I’m curious about why that idea persists today,” Wiesen said. “Hitler’s father never knew who his own father was, but it’s been proved again and again that it’s almost impossible that this man was Jewish.” Ultimately, this myth — which Wiesen still hears regularly — “does a lot of psychological work,” Wiesen said. “It suggests that Jewish people brought the suffering of the Holocaust on themselves. There are very specific reasons around the origins of this myth, often having to do with antisemitism.”

More to say?

After all these years, is there still anything new to learn about Hitler and Nazi Germany? “That is the inevitable question,” Wiesen said. “How much more is there to say? The fact is, historians all think there is something new to say about a particular interest of theirs. Look at Lincoln; it’s been more than 150 years and there is no end to books about him.”

And there are indeed new perspectives to be uncovered, Wiesen points out. Within Germany or the United States, “you don’t find a ton of new documents, although certainly in both countries you still have people who go up to the attic and find something their relative brought back from the war or a batch of letters,” Wiesen said. “The more interesting thing now is that people are learning other languages next to German and going into Eastern European archives to learn more about the Holocaust.” And we are still learning about how the Nazi regime was perceived in other countries. In Iran, some contemporary accounts saw the Nazis as a “freedom fighter movement,” Wiesen said. “Also, Argentina, where some Nazis fled after the war, and the Middle East — that is where many of the untapped sources are.”