Infectious diseases specialist Ellen Eaton, M.D., is working to make sure that the unique needs of African Americans, the homeless, those with limited English, the disabled and the LGBTQ community are met during the COVID-19 pandemic. "Supporting community needs, not just medical ones, has been very eye-opening," she said. "It is a real peek behind the curtain at issues I never noticed before.”By this point, most of us living in the Birmingham area probably feel like we could recite public health recommendations for surviving the COVID-19 pandemic in our sleep: wash your hands, practice physical distancing, wear a mask when you are out in public. But these potentially lifesaving messages have not always spread equally to all members of our communities.

Infectious diseases specialist Ellen Eaton, M.D., is working to make sure that the unique needs of African Americans, the homeless, those with limited English, the disabled and the LGBTQ community are met during the COVID-19 pandemic. "Supporting community needs, not just medical ones, has been very eye-opening," she said. "It is a real peek behind the curtain at issues I never noticed before.”By this point, most of us living in the Birmingham area probably feel like we could recite public health recommendations for surviving the COVID-19 pandemic in our sleep: wash your hands, practice physical distancing, wear a mask when you are out in public. But these potentially lifesaving messages have not always spread equally to all members of our communities.

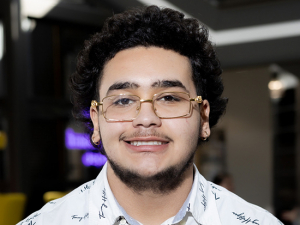

"One of the unintentional consequences of a lot of public health messaging is that we forget to translate," said Ellen Eaton, M.D., an assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases. Eaton is speaking about people with limited English, but the same applies to people with hearing impairments, seniors exposed to misinformation about the danger of COVID-19, well-meaning groups reaching out to the homeless and more, she said.

Eaton’s medical practice has always included people living with HIV, drug users, the homeless and other vulnerable populations. Now she is leading the Special Populations branch of the Jefferson County Department of Health as it responds to COVID-19. She oversees six teams focused on the unique needs identified among groups including the homeless, those with limited English, African Americans, the disabled and the LGBTQ community. "Supporting community needs, not just medical ones, has been very eye-opening," she said. "It is a real peek behind the curtain at issues I never noticed before.”

|

Ellen Eaton’s work is a stellar example of the UAB shared value of inclusiveness. Learn more about UAB’s seven shared values. |

For instance, press conferences with Jefferson County Health Officer Mark Wilson, M.D., and Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin include a sign language interpreter. "But the cameras didn't always have the interpreter in view — so when the mayor or health officer was speaking about masks or what businesses can open, many people were not able to understand," Eaton said. "Once our disabilities group brought that up, we were able to ask the news stations to make sure their cameras included the translator. And people started messaging and saying, 'Thank you so much. I can finally understand what's going on.'"

Much of the work “has been around awareness and communication," Eaton said. "We have done webinars targeting specific groups, run spots on radio stations targeting Spanish speakers and intentionally reached out to churches to let them know when there's a new testing site, put signage up in the public parks letting people know about safe ways to feed the homeless — instead of a buffet where people are trying to do good work in feeding the homeless but are actually putting them at risk for infection."

"One of the unintentional consequences of a lot of public health messaging is that we forget to translate.” |

Eaton talked herself into the Special Populations job. "A lot of my research intersected with the Department of Health around substance use," she said. "I knew Dr. Wilson and Dr. Willeford. I started reaching out to them to ask how we were going to address certain challenges. I asked enough questions that they realized I should be part of the response."

But the first step in responding well is to listen carefully, Eaton has discovered. "One thing I've learned is that listening to these populations will point you in the right direction,” she said. “Even small changes can make a big difference, like making sure that your signage has a phone number so that Spanish speakers, Vietnamese speakers and others can get the message, too.

“All of a sudden you've expanded the audience and brought in people who weren’t included before. That’s what we’re trying to do.”