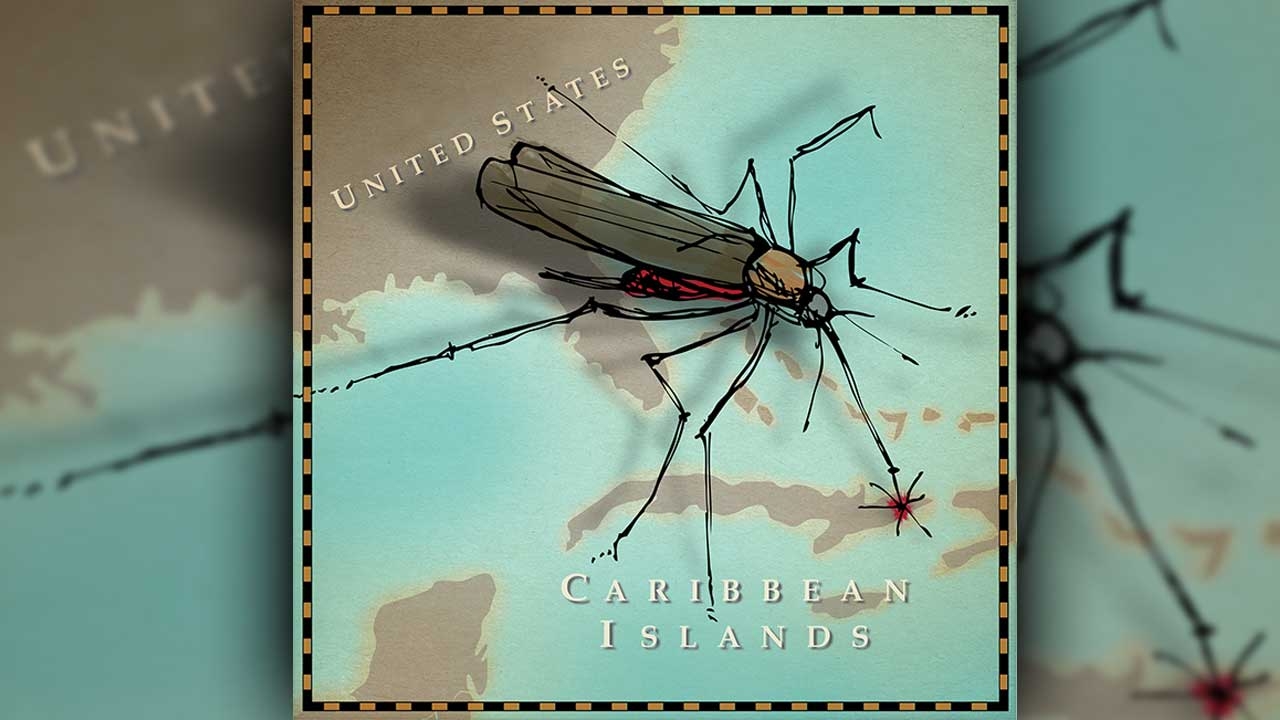

Don’t blame chickens for chikungunya, the virus making headlines for its spread in the United States in 2014. Rather, its winged carriers include mosquitoes and a far more effective disease distributor: air passengers.

At the beginning of August 2014, the 50 states were reporting nearly 400 cases of the disease, from Maine to Florida to Hawaii, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (The CDC has not officially counted any suspected cases in Alabama.) Nearly all of those cases were unfortunate souvenirs picked up by visitors to the Caribbean, where the disease jumped from zero cases before October 2013 to an estimated 300,000 today.

“The Caribbean is fertile soil for the virus, with the right mosquitoes, the right density of people, and poor sanitation,” says David O. Freedman, M.D., director of the UAB Travelers Health Clinic and professor of infectious diseases and epidemiology. With frequent air traffic between the islands and North America, and millions of travelers exposed to “a lot of circulating virus,” it was only a matter of time before chikungunya entered the U.S., Freedman adds.

At the beginning of August 2014, the 50 states were reporting nearly 400 cases of the disease, from Maine to Florida to Hawaii, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (The CDC has not officially counted any suspected cases in Alabama.) Nearly all of those cases were unfortunate souvenirs picked up by visitors to the Caribbean, where the disease jumped from zero cases before October 2013 to an estimated 300,000 today.

“The Caribbean is fertile soil for the virus, with the right mosquitoes, the right density of people, and poor sanitation,” says David O. Freedman, M.D., director of the UAB Travelers Health Clinic and professor of infectious diseases and epidemiology. With frequent air traffic between the islands and North America, and millions of travelers exposed to “a lot of circulating virus,” it was only a matter of time before chikungunya entered the U.S., Freedman adds.

These viruses are of the highest priority for the U.S. government. They represent both biologic threats and unmet medical needs, and the global burden of these diseases is enormous.

Targeting a Treatment

UAB School of Medicine researchers have kept an eye on chikungunya as it has migrated around the world from Africa and southeast Asia. The virus is one target for the new Antiviral Drug Discovery and Development Center (AD3C), a national research consortium headquartered at UAB that also will include scientists at Birmingham-based Southern Research Institute and four other universities around the country. Funded by a five-year grant of up to $35 million from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the AD3C also will develop therapies for diseases ranging from influenza and SARS to MERS, West Nile, and dengue. “These viruses are of the highest priority for the U.S. government,” says Richard Whitley, M.D., UAB Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics, director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, and AD3C principal investigator and program director. “They represent both biologic threats and unmet medical needs, and the global burden of these diseases is enormous.”

Debilitating Pain

Chikungunya is a Swahili word that translates to “all bent over with pain,” which is an apt description of symptoms that typically follow infection, Freedman says. "The hallmark is “a very severe arthritis—severe pains in the joints. Some people describe it as somebody sticking a knife into both shoulders at the same time.” Fever, rash, and flulike illness also are common. Most people recover in a few days, though a small percentage later develop a chronic arthritis that could last for a year or longer. “It’s a spectrum of disease” that affects individuals differently, Freedman says.

No antiviral treatments or vaccines currently exist for chikungunya—a situation that the AD3C is attempting to change. Its researchers will identify and inhibit enzymes essential for viral replication and expression of viral genes, with the center providing an infrastructure to accelerate the development of new drugs to benefit patients. AD3C scientists in Oregon and North Carolina already have discovered potential chikungunya targets and developed a test, or assay, to indicate successful hits; Southern Research’s robotic high-throughput screening facility will apply thousands of molecular compounds to see which ones take aim at the virus. The “best outcome” of the research would be successful therapies for chikungunya and other diseases over the next five years, Whitley says, adding that the national AD3C team “represents terrific intellectual talent to address these challenges.”

Until new drugs arrive, current chikungunya treatments address symptoms only, and they are familiar to anyone who has had the flu—anti-inflammatory drugs, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, good hydration, and so forth. “It’s not a diagnostic emergency,” Freedman says.

No antiviral treatments or vaccines currently exist for chikungunya—a situation that the AD3C is attempting to change. Its researchers will identify and inhibit enzymes essential for viral replication and expression of viral genes, with the center providing an infrastructure to accelerate the development of new drugs to benefit patients. AD3C scientists in Oregon and North Carolina already have discovered potential chikungunya targets and developed a test, or assay, to indicate successful hits; Southern Research’s robotic high-throughput screening facility will apply thousands of molecular compounds to see which ones take aim at the virus. The “best outcome” of the research would be successful therapies for chikungunya and other diseases over the next five years, Whitley says, adding that the national AD3C team “represents terrific intellectual talent to address these challenges.”

Until new drugs arrive, current chikungunya treatments address symptoms only, and they are familiar to anyone who has had the flu—anti-inflammatory drugs, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, good hydration, and so forth. “It’s not a diagnostic emergency,” Freedman says.

Here to Stay?

Will chikungunya stick around in the U.S. as it has done in other parts of the world? “That’s the million-dollar question,” Freedman says. In the Caribbean, Aedes mosquitoes transmit the virus between people. In America, however, “it’s 50/50 as to whether it becomes an endemic disease. The odds are against it, simply because other viral mosquito diseases common in the Caribbean, such as dengue, haven’t become established in the U.S.,” Freedman says. “It may have to do with the fact that the mosquitoes aren’t as dense or as prevalent in the U.S., where we have better sanitation.” Still,Aedes mosquitoes buzz around the eastern and southeastern United States—as far north as New York City during the warmer months, from about May to November. “If chikungunya did become established, it would likely be a summertime disease like West Nile virus or Lyme disease,” Freedman says.

Preventing mosquito bites is the best way to thwart infection—“at least 30 percent DEET on exposed skin every four to six hours if you’re going to be outdoors,” Freedman says. A trip to UAB’s Travelers Health Clinic is another precaution if you’re heading to the Caribbean or other destinations where chikungunya may be prevalent. “You should always go to a travel medicine clinic before a foreign trip because the specialists are aware of new outbreaks and risks that travelers face,” Freedman says. It’s a stop that could keep you from flying home with a painful reminder of your vacation in paradise.

Preventing mosquito bites is the best way to thwart infection—“at least 30 percent DEET on exposed skin every four to six hours if you’re going to be outdoors,” Freedman says. A trip to UAB’s Travelers Health Clinic is another precaution if you’re heading to the Caribbean or other destinations where chikungunya may be prevalent. “You should always go to a travel medicine clinic before a foreign trip because the specialists are aware of new outbreaks and risks that travelers face,” Freedman says. It’s a stop that could keep you from flying home with a painful reminder of your vacation in paradise.