Everyone knows someone whose life was stolen by cancer, but the devastation hits particularly hard among African Americans in the South.

“I have a cancer-riddled family,” said Clayton Yates, Ph.D., director of the multidisciplinary Center for Biomedical Research at Tuskegee University, the historically Black institution in the heart of Alabama’s Black Belt region. Yates’s grandfather died from prostate cancer, which is two to three times more deadly among African American men compared with American men of European ancestry. His maternal grandmother was diagnosed with breast cancer early in her life, which she survived. “However, she ended up passing away from colon cancer,” Yates said. His paternal grandfather recently passed away from pancreatic cancer. Each of these cancers disproportionately affects African Americans, “suggesting that family history is an important factor in developing cancer,” he said.

These losses inspired Yates to pursue cancer research. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology at Tuskegee, then went to the University of Pittsburgh for his doctorate and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Emory School of Medicine before returning to Tuskegee as an assistant professor. He had big ideas on new research directions for prostate cancer, but since “Tuskegee didn’t have a medical school, there were not enough resources to allow us to grow and develop these ideas,” Yates said.

Instead, the early-career scientist found seed money, and mentorship, in a partnership among Tuskegee, the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, and UAB’s O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. In 2006, the MSM-TU-UAB OCCC Partnership become one of the first to be selected for a National Cancer Institute program that pairs elite cancer centers with minority-serving institutions across the country for cancer research, education, and outreach. Partnership investigators, particularly from the minority-serving institutions, can access the university’s state-of-the-art technology and facilities, including genomics and imaging equipment, at discounted internal rates. Additionally, some of them have received secondary faculty appointments at UAB.

Yates worked closely with UAB pathologist William Grizzle, Ph.D., who had curated a vast biobank of tumor samples and other specimens from patients, including patients with prostate cancer. “Tuskegee is not a medical school,” Yates said. “We don’t see patients, so the tissue resources that Bill Grizzle supplied were critical to demonstrating that what we were seeing in our work in cell lines was actually happening in human beings.”

Yates’s research, fueled by pre-pilot and pilot grants from the Partnership grant, led to external funding from the National Cancer Institute and other major supporters of cancer research, including the Department of Defense. Today, Yates has earned grants worth more than $40 million, and he is the principal investigator at Tuskegee for the MSM-TU-UAB OCCC Partnership along with Vivian Carter, Ph.D., and Windy Dean-Colomb, M.D.

Mentoring young investigators

Yates is one of many investigators who credit the Partnership with accelerating their careers in cancer research. “The goal of this Partnership is to address the disparities in cancer happening now in our backyard — and to create the next generation of investigators with the skills to find new solutions for these problems,” said Upender Manne, Ph.D., lead principal investigator for the Partnership at UAB and professor and director of translational anatomic pathology in the UAB Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine Department of Pathology. (Manne is pictured at the beginning of this article above.)

Manne knows about the importance of early investments in research firsthand. When he arrived at UAB nearly 30 years ago, he became interested in genetic variations between Black and white patients with colorectal cancer. Although this type of investigation at the molecular level was rare in those years, his work received a major boost when Albert LoBuglio, M.D., then the director of the Cancer Center, selected Manne’s project for pilot funding. “I got $20,000, and I converted that to an R03 then to an R01 [NIH research grants] and an entire career in this field,” Manne said. “Pilot funding has a huge impact.”

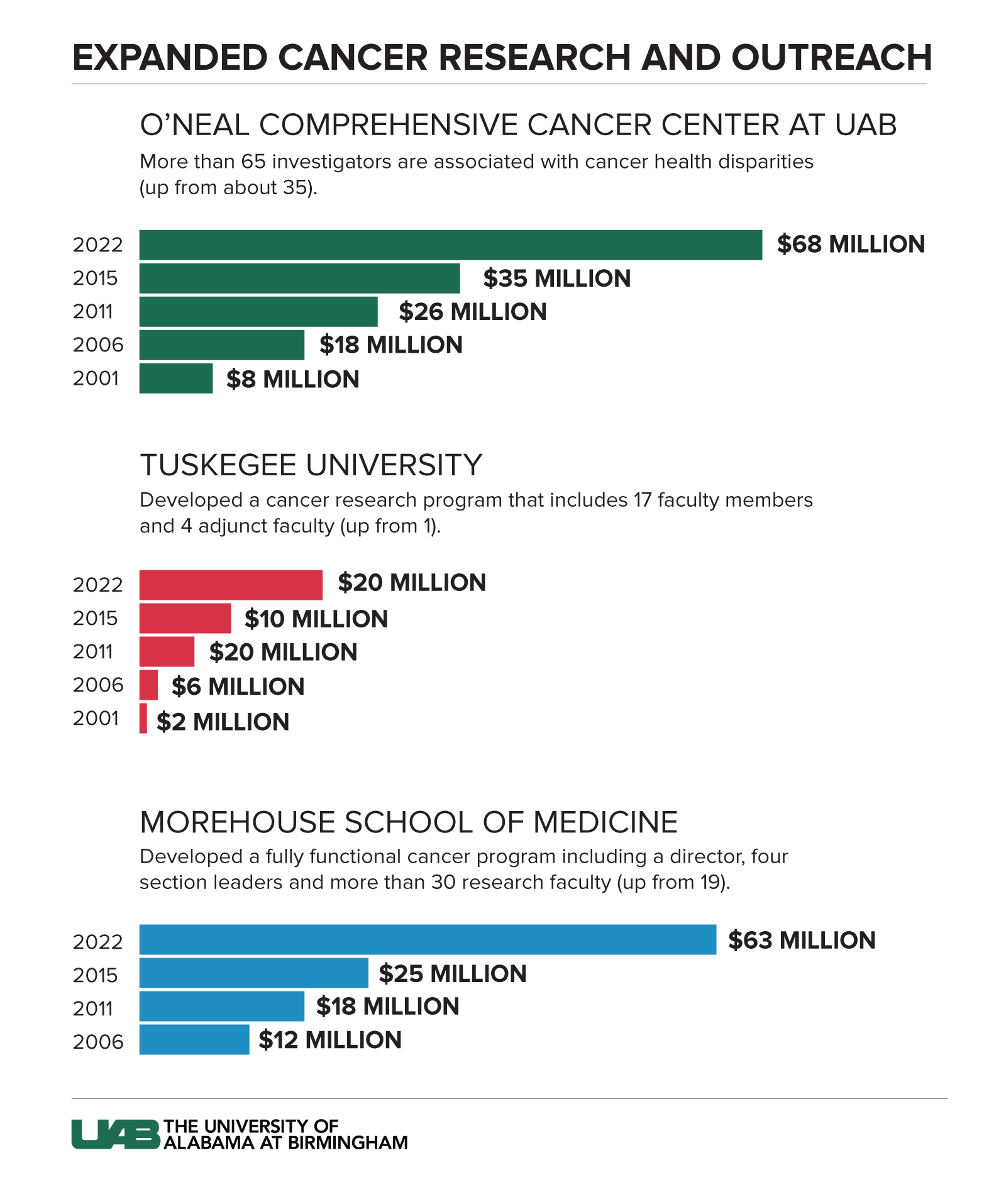

The proof is in the results. Before the Partnership began, there were 19 cancer research faculty at Morehouse School of Medicine; now there are 30, including a director and four section leaders. At Tuskegee University, there was a single faculty member focused on cancer research; now there are 17, and four adjunct faculty members as well. And at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center, there are now more than 65 investigators associated with cancer health disparities, up from about 35.

Moving to the next level

“UAB has long been at the forefront of the focus on health disparities, and this Partnership has truly empowered research productivity at all three institutions,” said UAB President Ray L. Watts, M.D. “We are proud of the work of Dr. Manne and his team, and this will continue to be a major focus of our efforts.”

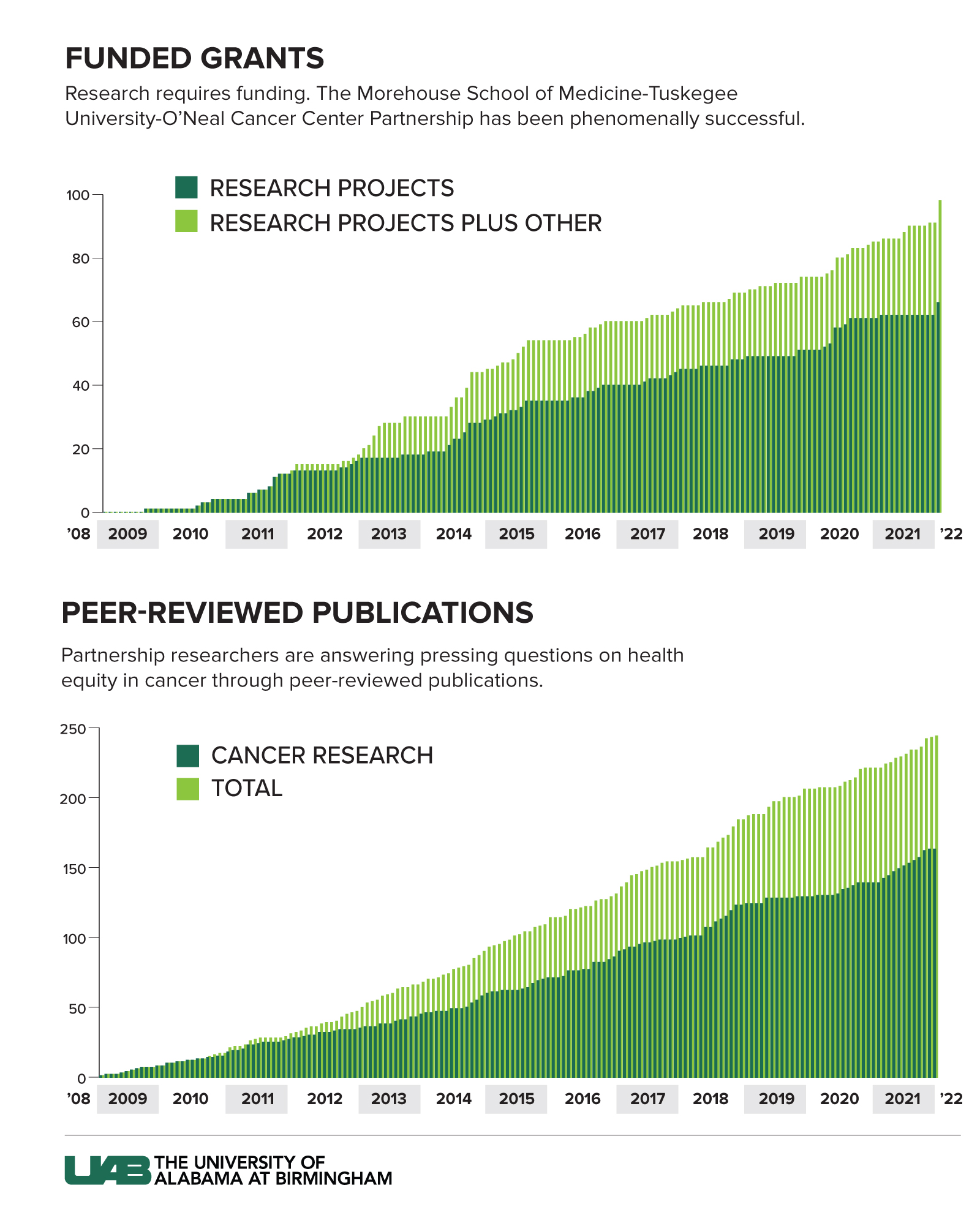

The MSM-TU-UAB OCCC Partnership traces its roots to individual partnerships between the Cancer Center and MSM and Tuskegee, established in 2001 by Edward Partridge, M.D., who would become the Cancer Center’s third director in 2007, and Mona Fouad, M.D., MPH, who would establish the groundbreaking UAB Minority Health and Health Equity Research Center in 2002. The original $15 million NCI grant to UAB, MSM, and TU in 2006 was renewed in 2011, 2016, and 2021. “We have received $80 million in grants for the Partnership, and we have generated more than $150 million in additional grants to investigators who are associated with the Partnership,” Manne said. In addition to more than 400 scientific publications, that funding has enabled the development of several potential anti-cancer compounds each at Tuskegee, Morehouse and UAB, he added. “They are really looking promising to move to the next level of conducting clinical trials.”

Not every budding scientist is intuitively drawn to cancer work, as Yates was, or even imagines a life for themselves in the lab. The Partnership’s education efforts extend from middle- and high school students at Tuskegee, undergraduates (also at Tuskegee), graduate students and medical students at Morehouse and UAB, all the way to postdoctoral fellows and early-stage investigators such as Yates. Each level has a year-long program that gives participants a hands-on view of cancer research, an introduction to the problems of health disparities and interaction with working scientists. Manne also has received support from UAB to run a Partnership Research Summer Training Program (PRSTP) for undergraduates from other minority-serving institutions. (See “A summer in the lab.”)

Older students contribute to actual cancer research projects in the labs of UAB researchers, providing them with valuable experience and even co-authorship of publications. For early-stage investigators and postdocs, there are the pre-pilot/pilot funding opportunities, along with mentorship in submitting grants and writing manuscripts. (At UAB, Manne hired a professional scientific writer and editor, retired faculty member Donald Hill, Ph.D., to work with Partnership participants on these key skills.)

In additional to the comprehensive cancer research partnership with Morehouse School of Medicine and Tuskegee, the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center established another NCI-funded cancer research and education partnership with Alabama State University in Montgomery from 2013-2019.

Partnering for precision medicine

While the Partnership develops more investigators interested in cancer health disparities research, and more potential treatments, it also is impacting affected communities today. “Although research is important, it is not enough to eliminate cancer disparities alone,” said Isabel Scarinci, Ph.D., multiple principal investigator for the Partnership at UAB and senior adviser for globalization and cancer at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. “We need to get these evidence-based approaches to the ones experiencing the highest burden of disease and train the next generation to continue this mission.”

Outreach efforts from the Partnership have reached thousands in the communities around Morehouse and Tuskegee and have connected more than 500 African American patients with cancer to cutting-edge clinical trials at UAB.

For its latest five-year grant cycle, the Partnership is focusing on the hottest area in cancer care: precision medicine. Gene sequencing can now guide doctors to the right treatment for individual groups based on the specific mutations found in each patient’s tumor. But

nearly 80 percent of participants in the research studies that are guiding precision medicine are individuals of European descent, even though this group represents only 16 percent of the world’s population. “What we have so far is primarily middle-class white patient participation in clinical trials,” Manne said. “The same drug that worked in white patients is piped into everyone, but there is no guarantee that the drug is working for all patients in the same way.”

In fact, research by Manne, Yates, and many others has demonstrated that genetic variations that occur with higher likelihood in certain racial and ethnic groups play a role in poorer outcomes in colorectal cancer (Manne), prostate cancer (Yates), and breast cancer (both).

Collecting samples of tissue and blood from African American cancer patients is critical to making sure that this population can benefit from precision medicine’s promise. Yates points out that without access to such a biorepository around prostate cancer, his own work would not have been possible.

Convincing people to participate means explaining the benefits and science behind precision medicine in a relatable way. With its Total Cancer Care initiative, Morehouse has already collected tissue samples from 2,000 African American cancer patients. Now, that effort will be replicated at Tuskegee and UAB.

“We are excited to implement the first targeted genomic education program in the Deep South,” said Brian Rivers, Ph.D., director of the Morehouse School of Medicine Cancer Health Equity Institute and lead principal investigator/co-director of outreach activities for the Partnership.

Setting a template beyond cancer

The Partnership has been so successful that it helped convince the NIH to select UAB and Tuskegee as the first recipients of the

Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation, or FIRST, program. The $13.7 million grant will hire and train 12 new research faculty members across both institutions with the goal of creating systemic and sustainable culture change. (The new hires’ areas of research will include cancer, obesity and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neuroscience.)

“This was a highly competitive program,” Yates noted. “By leveraging the infrastructure of both institutions, and with the data we could show from the success of this cancer research partnership, we were able to be selected.”

“We have a well-established, highly productive cancer research partnership,” Manne said. “This FIRST grant will extend that to other diseases.”

A summer in the lab

“Tremendous institutional support” has allowed Manne to develop new opportunities to engage budding young scientists in cancer research beyond the original MSM-TU-UAB OCCC Partnership. In 2013, he started the Partnership Research Summer Training Program, or PRSTP, with the goal of providing undergraduates, especially minority students, opportunities to work in the cancer research laboratories of UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center for two months during the summer. Nearly 80 students have participated in the program, with many going on to medical school, dental school, nursing school, other professional schools, or graduate school. (A similar partnership between UAB and Alabama State University was funded by a P20 grant from the National Cancer Institute for five years and resulted in several participants going to medical school, Manne notes.)

Madison Wright, Ph.D., participated in the PRSTP in 2016 while he was an undergraduate at Jacksonville State University. He worked in the lab of Soory Varambally, Ph.D., director of Translational Oncologic Pathology Research in the Department of Pathology, studying P4HA1, a biomarker and potential drug target for colon cancer. Wright completed his doctorate in chemistry at Vanderbilt University in August 2022, where he studied protein-protein interactions implicated in protein misfolding disease states. Wright was originally a premed major, but he found that he liked science so much that his advisors at Jacksonville State suggested he look into a research career. “I said, ‘What do I need to do to get a Ph.D.?’ Wright recalled. “They said, ‘Well, they will want you to have research experience,’ but it was one of those situations where you have to do research before anyone will hire you to do research.”

Wright discovered PRSTP, and “honestly I don’t think I would have gotten into Vanderbilt without it,” he said. “It gave me my first research experience and that’s where it all clicked for me. Having a letter of recommendation from Dr. Varambally and the whole PRSTP experience — I think that was one of the most pivotal moments of my research career so far.”

Skye Opsteen, who took part in PRSTP in 2017, also worked in Varambally’s lab. She is currently in the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science Predoctoral Clinical/Translational Research (TL1) Program, pursuing a master’s degree between her second and third years of medical school at UAB. “Coming in as a freshman with no experience in research, I got to learn how to read research papers, how to run Western blots to look at protein levels and how to search for genes in UALCAN [a widely used database of cancer genes that Varambally developed] and how to narrow down results,” Opsteen said. Her project was focused on bioinformatics more than wet-lab experiments, which prepared her for a booming area of cancer research, she said. “Being able to sort through really large datasets is essential to any research you are doing now,” Opsteen said. “It set me up for success later down the road.”