The last time Lee Meadows, Ph.D., visited a Birmingham high school as a lecturer on evolution, he began with a disclaimer: “I’m not out to change what you believe.”

The relief in the classroom was almost visible. The kids had been gearing up for another skirmish in a culture war. Meadows, a UAB School of Education professor, had seen his own tour of duty: The Christian evangelical had grown up in a fundamentalist community where his interest in science was suspect, and he had spent part of his classroom career trying to figure out how to broker peace over evolution education in the heart of the Bible Belt.

Now Meadows helps to guide teachers as they approach the sensitive subject. His ideas and methods have attracted the attention of educators nationwide—and even the Smithsonian Institution.

Follow the Evidence

Alabama does not require evolution in its core curriculum, yet understanding evolution is essential in modern society whether you believe in it or not, Meadows says. In his essays and 2009 book, The Missing Link, Meadows agrees that teachers are never going to be able to find harmony between evolution and students’ conflicting religious views—so they shouldn’t try.

Lee Meadows

Lee Meadows“The first thing I tell teachers is that it is not their job to resolve the conflict, and that usually comes as a great relief,” he says. The fight is deeper than science vs. religion: Part of the blame, Meadows argues, lies with would-be luminaries who not only teach science but also crusade against the supernatural. “They begin with the idea that any religious beliefs that oppose evolution are wrong and bad,” he says. “But the last thing a science teacher needs to do is try to use evolution to beat those beliefs out of kids’ heads. I think that’s immoral. A public school science teacher should never guide kids to question their faith.”

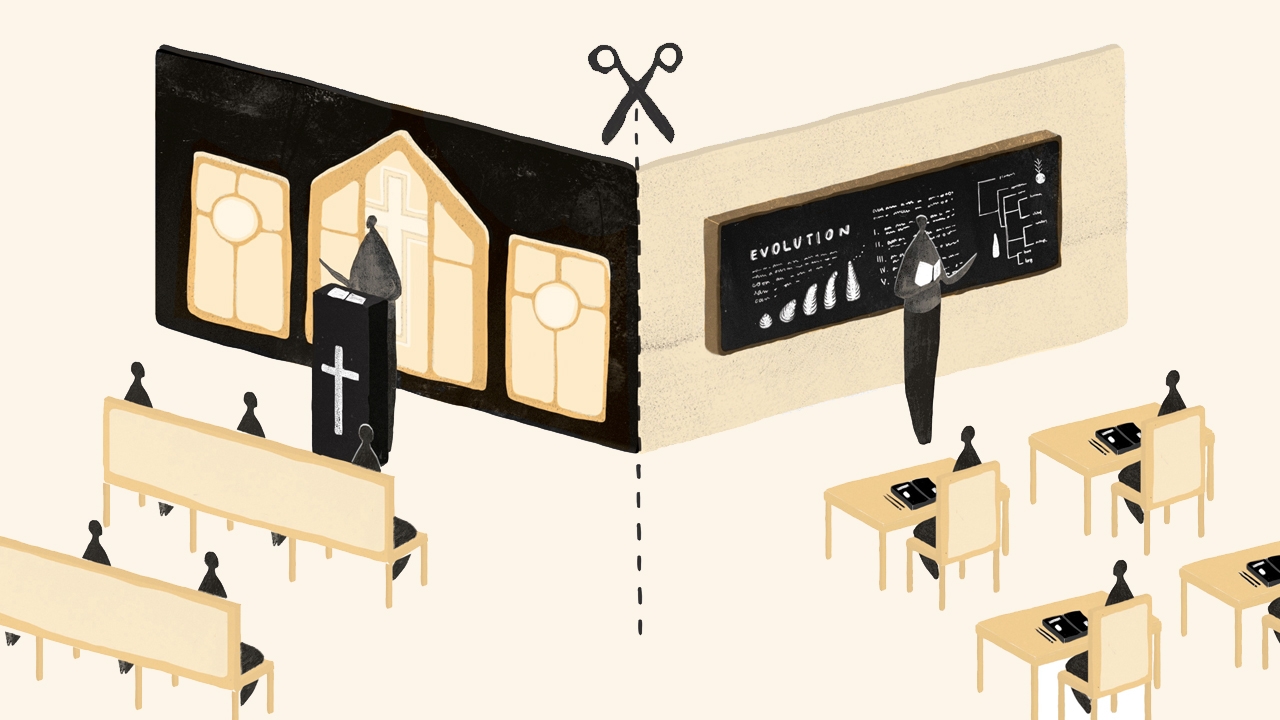

Meadows emphasizes inquiry-based lesson plans designed for understanding, but not belief: “You start with a question, you engage the kids with evidence, and then get them to begin to answer that question using a scientific explanation for the evidence,” he says. The idea isn’t to level the playing field between creationism and evolution, but to keep them in totally separate spheres. “The kids have to understand what scientific explanations are and that scientific explanations can’t invoke God,” he says. “Teachers need to begin with, ‘I’m not saying any thoughts you have about God aren’t true. I’m saying you have to come up with a scientific explanation for the evidence you just saw.’”

National Impact

Meadows’s work has earned him a reputation among other educational bodies trying to navigate evolution through cultural minefields. The National Center for Science Education commended The Missing Link, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History invited Meadows to serve on its Broader Social Impacts Committee, which oversaw the development of an exhibit on human origins.

Recently, Meadows has advised the Smithsonian on curriculum design for the high-school Advanced Placement program, which has been retooled in recent years to include more content on evolution. He is pleased to see that Alabama ranked first in the nation in 2014 for the percentage growth of students earning passing scores on AP tests in science, as well as math and English, according to the A+ Education Partnership. Meadows also co-directs the new UABTeach initiative, supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant, which encourages and prepares students pursuing majors in science, math, and technology to choose careers in the classroom.

Both developments are promising, Meadows says. He notes that his mission isn’t about evolution or religion, but about improving science education in the South, which will begin in the minds of both students and teachers. That may not stop the culture war, but it might help keep learning out of it.

• Learn more about the research under way in the UAB School of Education.

• Give something and change everything for faculty and students in the School of Education.