Beyond the familiar eye chart, there is the iPad.

In the School of Optometry, the high-tech tablet has become a therapeutic tool for correcting amblyopia, commonly known as “lazy eye.” And it’s just one of several surprising new approaches to pediatric vision care that UAB eye specialists are pioneering. The outcomes could set new standards for treating conditions that can have a long-lasting impact on a child’s vision—and his or her ability to function effectively in school.

All together now

Take, for example, 9-year-old Ben Hairston of Mountain Brook, Alabama. He struggled with reading since he started elementary school—confounding his parents and teachers, because otherwise he is a good student. His sight didn’t appear to be the problem. “Ben never complained that his eyes bothered him, and he had them checked at school,” says his mother, Monique Hairston. “But it would take him 20 minutes to read two pages.” He was examined for dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but neither diagnosis fit. Ben’s reading lagged even after Monique enrolled him in extra classes during the summers and hired tutors.

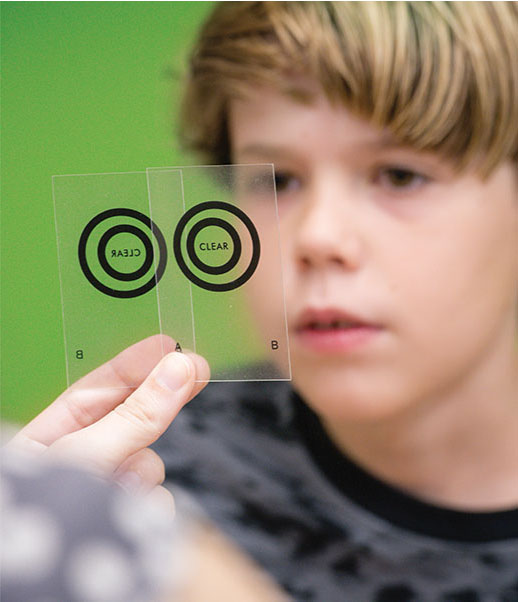

Vision therapy exercises help Ben Hairston train his eyes to work as a team. (At top) Optometrists use a keratometer to learn more about a patient’s myopia.

Vision therapy exercises help Ben Hairston train his eyes to work as a team. (At top) Optometrists use a keratometer to learn more about a patient’s myopia.By the time Monique heard about the School of Optometry’s Vision Therapy Clinic, she was ready to try anything—and it was life changing from the first visit, she says. Clinic chief Kristine Hopkins, O.D., M.S.P.H., associate professor of optometry, diagnosed Ben with convergence insufficiency, a condition in which the eyes have trouble working as a team when looking at nearby objects. “Often these patients have a difficult time staying on task or completing reading assignments,” Hopkins explains. “Parents will say their child passed the vision screening test, and those are good for finding kids who need glasses. But they are not adequate for picking up eye muscle problems.”

The Vision Therapy Clinic treats convergence insufficiency and similar issues such as tracking—the ability to follow words across a page or the path of a moving object—with something akin to physical therapy for the eyes. Optometrists challenge children to see a target moving toward their nose, an image on a computer screen, or a dancing flash of light from a prism. “To keep things in focus, they have to converge their eyes,” Hopkins says. “These skills help train the eyes to converge more effectively.”

The typical therapy program includes about 12 to 15 visits, one hour a week. Halfway through, Ben improved dramatically in his reading, checking out books unprompted from the library and progressing through them at a quicker pace. His performance on school reading tests also rose, Monique reports.

UAB’s efforts to encourage eyes to work together could have an impact beyond Alabama. The School of Optometry was among seven centers selected for a major National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study to gauge the effects of convergence-insufficiency therapy on reading, attention, and comprehension in children. Scenarios like Ben’s motivate researchers to identify and treat more kids with undiagnosed convergence insufficiency or similar eye muscle problems—or those who are misdiagnosed with attention problems—before they fall behind in school.

Slowing nearsightedness

“It’s like wearing a retainer, but for your eyes”: Optometry professor Katherine Weise, O.D., M.B.A., is describing orthokeratology (Ortho-K), an innovative treatment for pediatric myopia, or nearsightedness. Ortho-K’s rigid contact lenses, worn each night, temporarily reshape the cornea. “Our goal is clear vision when the child wakes up,” Weise says. “We also hope to reduce the lifelong blur associated with uncorrected myopia.” That is just one treatment option available to young patients at UAB Eye Care’s Myopia Control Clinic, established last year amid a worldwide increase in cases of the condition. Another solution is multifocal contact lenses, which contain more than one prescription in a single lens.

Fun glasses and video games may be the future of amblyopia treatment.

Fun glasses and video games may be the future of amblyopia treatment.Myopia occurs when the eye grows too long, focusing images in front of the retina and causing people to struggle to see objects at a distance. There is no cure, but recent research has shown that it can be mitigated by slowing further eye growth in children. The School of Optometry was among four centers to participate in a 14-year NIH-funded study of pediatric myopia patients. “We provided a ton of information about this condition and proof that we could slow down growth of a human body part—the eye—with an optical intervention,” Weise says. The results have spurred greater interest in new treatments. Now the school has joined nine other sites nationwide in an NIH-supported project investigating an especially promising solution—the use of 0.01-percent atropine drops, thought to slow myopia progression by about 60 percent in school-age children.

Divide and conquer

Another new study could help revolutionize treatment for lazy eye. Patients with the condition “have one good eye and one bad eye,” Weise says. “That could come from a perfectly lengthened eyeball paired with a really short one or a very long one, or it could result from an eye turn, in which one eye is straight and the other is turned.” Conventional treatments include using an eye patch to cover the stronger eye, forcing the other one to work harder. That has proven to be effective, but pediatric patients aren’t always fans of the patch.

Fortunately, the iPad may be able to help these reluctant pirates. In the study, the children play specially designed video games while wearing glasses that have one red lens and one green lens. “With this iPad game, we can vary the contrast between the eyes, and the different colors help us do that,” Weise explains. “So one eye sees objects in red, and the other eye sees the half that’s green. Unlike the old-school patch method, patients have to use both eyes at the same time, which may stimulate vision development better.”

The School of Optometry is partnering with the School of Medicine’s Department of Ophthalmology to recruit patients for this study and the atropine study for myopia. When doctors with different training share their expertise, they often come up with ideas neither would have thought of on their own, Weise notes. And all those innovations bouncing back and forth will help chart a new course for pediatric eye care. “We’re creating the answer for our patients, not just following the textbooks,” Weise says.

An Early Look

The School of Optometry and the Department of Ophthalmology suggest that most children receive vision screenings from their pediatrician by age 3 and at subsequent checkups. Most pediatricians will recommend visiting an eye doctor for a more comprehensive eye exam if there are any concerns. That exam should include dilating eye drops.

For families struggling to afford much-needed eye care for their children, Weise and Hopkins recommend Sight Savers America, an organization that works closely with UAB. The group provides screenings, helps coordinate insurance and care, and can even provide glasses. “Their support helps us see more kids,” Weise says.