Six patients had tested positive for COVID-19 in Dr. Monica Williams's Huntsville ER room as of Monday, though she said that number may have been low.

"I'm aware of at least two people who were hospitalized, whose initial tests were negative, whose subsequent tests were positive," she said.

She thinks that could be because viral counts are too small for detection at some phases of the disease.

A woman delivers medical supplies at a screening clinic at Hartselle Family Practice, organized by Decatur Morgan Hospital, on Tuesday, March 24, 2020, in Hartselle, Ala. Those who meet the criteria for COVID-19 testing are sent to another site. (Dan Busey/The Decatur Daily via AP)AP

A woman delivers medical supplies at a screening clinic at Hartselle Family Practice, organized by Decatur Morgan Hospital, on Tuesday, March 24, 2020, in Hartselle, Ala. Those who meet the criteria for COVID-19 testing are sent to another site. (Dan Busey/The Decatur Daily via AP)AP

"When I write a cause of death on the death certificate, I don't know whether they're COVID positive or not. All I can say is, you know, 'they appeared to have had respiratory failure, cause unknown,'" said Williams, who is also watching for asymptomatic patients experiencing cardiac arrest and coronavirus.

Issues with testing are one reason why coronavirus may be the underlying cause of someone's death but never make it to a death certificate or into a public tally, experts say.

In Alabama, the rollout of coronavirus testing has been limited and delayed. As of Tuesday, 14,765 Alabamians had been tested for the disease and there were 2,054 confirmed cases, according to ADPH. Private labs are also testing for coronavirus, but they are only required to report positive cases, making it difficult to get a complete testing picture for the state.

When patients arrive in the emergency room with trouble breathing, doctors may not know for sure if they have coronavirus. If those patients pass away, their families are no longer in the emergency room to help doctors understand the back story.

"I'm never going to know because I'm not going to test them in arrears and we generally don't do autopsies on those deaths," she said.

Cause of death

As of Tuesday, there were 39 known deaths from Coronavirus in the state.

But belying the tracking of coronavirus deaths is an underlying problem that researchers have identified for decades.

"Belive it or not, most physicians are not trained how to complete a death certificate," said Dr. Randy Hanzlick, a retired forensic pathologist and former chief medical examiner of Atlanta who wrote how-to manuals for physicians on completing death certificates.

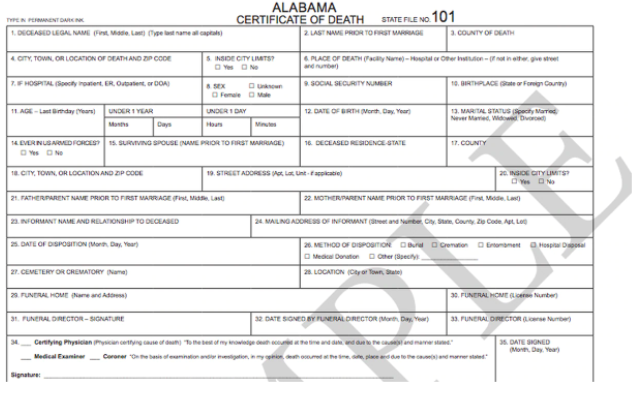

Death certificate forms have a space for primary, as well as secondary, underlying causes of deaths. Hanzlick says physicians often write the immediate cause, for example pneumonia, and don't necessarily write the underlying cause, for example, hypertension.

There's been study after study done over the years that show that when you use death certificate data to tabulate things, in many instances, you get a lower than real count," he said.

Hanzlick says hospitals often see a rotation of medical residents and interns tasked with completing the forms, and training is a perpetual need.

Alabama Certificate of Death

Alabama Certificate of Death

Al.com reached out to physicians in states like Oregon, Missouri, Georgia, and Arkansas who reported a range of practices for tallying deaths and for marking cause of death when COVID-19 symptoms are evident, but the patient was not tested or did not test positive.

In some places, physicians said they have been advised by hospital administrators to carefully document cases where COVID-19 is suspected.

The Alabama Department of Health said in an email to al.com Monday that it would add CDC guidance on certifying COVID-19 deaths to its website for medical certifiers.

Annoying Extra Step

David Mehr, a geriatric medicine doctor at University of Missouri Health Care, says the online death certificate form used in his state is not intuitive and can be complicated for a new practitioner.

For more seasoned physicians, doubling back to fill out a death certificate later on with secondary causes of death can be an annoying extra step.

"Physicians can be pretty sketchy in terms of what they put down, so they may not do a very thorough job about it," said Mehr, adding that no one gets paid to fill out a death form.

"There's no particular incentive to do it carefully other than if you put something down that doesn't make any sense or is not a correct diagnosis, they're going to bounce back to you," he said.

Finding the 'initiating event'

Dr. Greg Davis, Chief coroner and medical examiner for Jefferson County and a professor at UAB, says it is too early to know whether COVID-19 deaths are being underreported.

"Death certificates aren't infallible documents," he said, but added that the degree of attention on the disease makes it less likely to be overlooked by physicians.

He says at the county's coroner's office, they are documenting when COVID-19 is a suspected cause of death. That information will go to the ADPH to parse through later for an updated death tally.

"Anytime you're certifying a death, you want to go all the way back to what was the initiating event that when that happened, that's what set a person on the downward course that ended in death."

Davis says cause of death data is profoundly important. In aggregate, it determines the spending of billions of federal dollars for healthcare research.

For coronavirus, understanding who died from the disease and under what circumstances could be critical information to developing a virus or for knowing how long to practice social distancing.

No "probable" option

For physicians on the frontlines facing uncertainty about what's ahead, like Dr. Williams in Huntsville, having some idea of a death rate for the disease is helping her team prepare for what may come.

She says she has read guidance from the CDC, which collects cause of death data from states, asking physicians to note "probably" or "presumed" COVID-19 deaths.

But as a healthcare professional, she says she is not comfortable with that level of guessing, and the online death certificates she uses don't give a "probable" option.

"We tend to not want to put things that we can't know for sure," she said, adding that there's a variable practice among doctors.

"If we're uninformed, we're going to err on the side of not writing (it)."