Early in her career, LaToya Melton worked for a small nonprofit. She wasn’t making too much money, but she and her young daughter were getting by. Melton’s main hang-up, she said, was health insurance. Her employer covered insurance for a single individual, but the family plan was prohibitively expensive, and she didn’t qualify for Medicaid or the Alabama Department of Health’s ALL Kids low-cost comprehensive health care program.

Early in her career, LaToya Melton worked for a small nonprofit. She wasn’t making too much money, but she and her young daughter were getting by. Melton’s main hang-up, she said, was health insurance. Her employer covered insurance for a single individual, but the family plan was prohibitively expensive, and she didn’t qualify for Medicaid or the Alabama Department of Health’s ALL Kids low-cost comprehensive health care program.

“I had a car note, rent and daycare to pay for,” Melton said. “I was looking at $600 a month for medical insurance.”

So she opted out — only for her daughter to contract the flu just a few months later, and Melton was forced to pay out-of-pocket for a trip to the doctor and the necessary prescriptions.

Melton, now an assistant professor of field education in UAB’s Department of Social Work, did not become homeless because of those medical bills, but she says that often happens to people buried in health care debt. She always thinks of that experience — of her daughter needing pricey care and medicine while the two were uninsured — when trying to explain the various factors that, when added up, can lead a person or family to be homeless.

“When a family is faced with a situation like that, the question, depending on where the parent or parents work, often becomes, ‘Do I pay for medicine for my child or do I pay for rent or groceries?” Melton said.

On this sprawling urban campus where many medical, educational and social services intersect, employees and students need to understand homelessness and learn to interact with homeless individuals in ways that are safe and respectful for both.

By the numbers

More than 3,400 Alabama residents are homeless on any given day, according to the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). That 2018 estimate includes 280 family households, 339 veterans, 158 unaccompanied young adults ages 18-24 and 540 chronically homeless individuals.

Birmingham’s homeless population comprises a significant portion of Alabama’s total count — more than 2,900, per the most recent estimate in a needs assessment submitted to the City of Birmingham in 2017 by members of the UAB Department of Sociology. According to that report, more than 29 percent of homeless people in Birmingham are chronically homeless, which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines as someone with a disabling condition who has been homeless for a year or more or who has had at least four episodes of homelessness within a three-year period.

In 2015, HUD reported that, while homelessness across the nation was decreasing overall, it was increasing in urban centers — 3% that year.

The police perspective

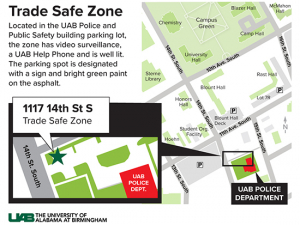

Because of UAB’s urban location, employees and students may encounter transient individuals around campus. Kenneth Spencer, captain of the UAB Police Department Patrol Division, shares his recommendations for staying alert and safe. Q: I saw a homeless person on a campus sidewalk. Should I call the police? Q: What should I do if something seems wrong? Q: How can I best stay safe while traveling around campus? Q: I don’t want to call the UABPD if there’s no real threat. What do I do? |

Understanding homelessness

Homelessness is a complicated problem, according to the Urban Institute (UI), a nonprofit research organization that collaborates with philanthropists, social services providers, community advocates, business and civic leaders to combat homelessness. No single federal organization focuses on homelessness, according to UI; the work is spread across 19 agencies, which spend about $5 billion per year on their efforts, much of which funnels down to the local level.

Homelessness isn’t a term that applies only to someone is living permanently on the streets or in their car, although that is true of some. A person can be defined as homeless by HUD if they fall into one or more of these four categories:

-

People who lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence or those discharged from an institution where they resided for 90 days or fewer who lacked a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence before entering that institution

-

Individuals or families who soon will lose their primary nighttime residence

-

Individuals fleeing domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking or other dangerous conditions related to violence against them or a family member

-

Unaccompanied youth and families with children defined as homeless under federal statues

Who homelessness affects

Many kinds of people can find themselves homeless. More than 66% of Birmingham’s homeless individuals have high school diplomas or have taken college courses, and 6% have trade school certificates, according to the 2017 report.

One of the biggest misconceptions about homelessness, Melton says, is that it's a choice. Rather, it occurs from a combination of two things: a lack of resources and the absence of support systems.

“Many people live paycheck-to-paycheck,” Melton said. “If someone loses a job, there may not be any savings or the ability to borrow from family or friends to maintain the bills or keep the utilities on. If you’re unable to pay bills, you get evicted. It’s hard to recover from that.”

Women face specifically difficult barriers after a job loss or when fleeing a domestic violence situation, Melton says. Many shelters do not allow low-income women to enter with their older male children; for example, Birmingham’s YWCA temporary housing does not admit boys older than 12 — which can prevent women from seeking shelter there.

“If I have a son that’s over the age of 12 and he can’t go to the shelter with me, as a mom, the only decision I have left if there are no other resources is to stay in my car,” Melton said, adding that while there are other male-oriented shelters available, many moms balk at the thought of sending an adolescent alone to temporary housing with adult men.

Before joining the social work faculty about a year ago, Melton was a social worker in Birmingham’s VA Hospital. There she worked with many homeless individuals whose mental illness or substance abuse prevented them from acquiring or keeping housing; however, she says other factors contribute to homelessness among veterans.

Many veterans or older adults are eligible for social services — veterans benefits, disability and Social Security, for example — but are not eligible to receive their payouts directly. For them, a payee is appointed, often a family member or other authorized representative. Melton says this pay structure can cause issues, especially if the payee does not use the money to provide for the social services recipient.

“Sometimes people take advantage of the payee system,” she said. “If they’re not providing that income to the intended recipient, that can lead to homelessness.”

LaToya Melton, assistant professor of field education in UAB’s Department of Social Work

LaToya Melton, assistant professor of field education in UAB’s Department of Social Work

Other barriers to home security include individuals who have felonies, specifically sex offenders, Melton says, because housing is significantly restricted by the proximity to schools or whether an apartment complex also houses families with young children. Additionally, if a person has a low credit score, it can be difficult to find safe and secure housing.

“Homelessness can happen to any of us. Anyone can experience a crisis,” Melton said. “There is no amount of money, no education degree that can prevent it. It’s all dependent on what type of support you have and what resources are available to you.”

How you can help

UAB already leverages much of its medical expertise to help city residents in need: The School of Dentistry hosts an annual day of community service to provide teeth cleanings, fillings and extractions at no cost to underserved populations, and the Division of Infectious Diseases partners annually with One Roof to provide complimentary flu vaccines to Birmingham’s homeless during National Homeless Awareness Week. In December 2018, UAB Eye care saw its 1,000th patient during its fifth annual Gift of Sight event, which provides comprehensive eye exams and glasses for low-income or underinsured patients.

Additionally, the UAB Benevolent Fund, which offers employees a unique blend of charitable giving opportunities, supports several local organizations that work to end homelessness in the Birmingham community. Learn more about each organization and consider making a payroll-deducted designation.

-

Pathways is a United Way agency that services approximately 1,600 women and children experiencing homelessness in the Birmingham area each year. Choose designation 077 to contribute.

-

Priority Veteran, also a United Way of Central Alabama partnership with support from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Supportive Services for Veteran Families, is an assistance program focused on serving military veterans and their families who are homeless or at immediate risk of becoming homeless. Choose designation 640 to contribute.

-

The Salvation Army is a Christian-based service organization that offers emergency housing for men, women, children, families and veterans, in addition to their My Home program, which helps homeless individuals transition out of the shelter system and into permanent housing. The organization also assists with mortgage and rent payments, utility bills, clothing and food to help prevent homelessness from occurring. Choose designation 116 to support the Greater Birmingham branch and 058 for the Walker County branch.

-

The Travelers Aid Society links individuals in transition or crisis to stability and security, and connects low-income or disabled adults to medical care and a healthier quality of life. Choose designation 060 to contribute.

-

The YWCA of Central Alabama provides affordable housing, quality child-development programs for children of homeless and working poor families, domestic violence services and social justice programming for women, children and families in Birmingham. Choose designation 070 to contribute.

-

The Blazer Kitchen combats food insecurity in the UAB community by providing healthy food, resources and referrals to employees, students, patients and their families.

Students and employees can also check the online platform BlazerPulse to find opportunities to engage in the community through service-learning and volunteer opportunities.

UAB is committed to fostering a safe and inclusive environment for all Blazers. From mobile apps to bus escort services to B-Alerts and more, make sure you’re up to date on all the ways to stay safer on campus.

UAB is committed to fostering a safe and inclusive environment for all Blazers. From mobile apps to bus escort services to B-Alerts and more, make sure you’re up to date on all the ways to stay safer on campus.