The study intersection at University Boulevard and 14th Street is one of the most heavily used crossings on campus. Participants in a new UAB study will help test an app designed to keep pedestrians safe.

The study intersection at University Boulevard and 14th Street is one of the most heavily used crossings on campus. Participants in a new UAB study will help test an app designed to keep pedestrians safe.

Smart cruise control, lane assist, autonomous braking: Today’s cars come with a host of safety features to help drivers in our distracted era. Wouldn’t it be great if pedestrians could get some help, too?

That’s the concept behind a new UAB study now enrolling participants. Researchers need 400-plus people who routinely cross the campus’s busiest intersection at University Boulevard and 14th Street (anchored by the Hill Student Center, Heritage Hall, Campbell Hall and the Mini Park). Their mission: to test an app that warns distracted pedestrians when they’re headed for danger. Participants will receive $50 for taking part. More important, they could help save lives.

The problem: Pedestrians are dying

Every year, 6,000 pedestrians are killed in the United States by collisions with motor vehicles and 180,000 are injured.

| To enroll in the trial, send an email to kevin329@uab.edu or call 205-934–4068. |

The problem has been getting worse: Between 2010 and 2015, pedestrian deaths rose more than 25 percent.

The new UAB study is testing a high-tech solution called StreetBit. Small, cheap radio beacons, installed on lights and lampposts, communicate with a custom-designed app on their phones. If the system detects they are distracted, pedestrians hear and see an alert before they step out into traffic.

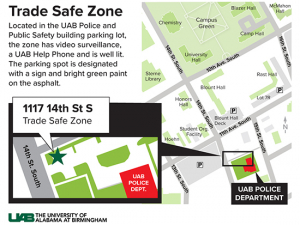

Yellow lines show the approximate range of the Bluetooth beacons around the study intersection. Beyond this area, the beacons will not communicate with the StreetBit app.

Yellow lines show the approximate range of the Bluetooth beacons around the study intersection. Beyond this area, the beacons will not communicate with the StreetBit app.

Distraction at UAB

The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is a partnership between psychologist David Schwebel, Ph.D., and computer scientist Ragib Hasan, Ph.D. Schwebel, director of the UAB Youth Safety Lab, has long been concerned about the impact of distraction from electronic devices. In 2018, he and colleagues published a study of pedestrian behavior on two urban college campuses: UAB and Virginia’s Old Dominion University. Both have heavily trafficked roads running through their campuses: University Boulevard/Alabama Highway 149 in Birmingham and Hampton Boulevard/Virginia Highway 337 in Norfolk. Researchers observed more than 10,500 pedestrians at these intersections during the course of two weeks and found that more than one-third were distracted while actively crossing the roadways — 19% were wearing headphones, 8% were sending messages and 5% were talking on their phones.

Why distraction is a big deal

A screenshot from the StreetBit app.

A screenshot from the StreetBit app.

The headphone numbers were particularly concerning, Schwebel said. “Our previous research shows that pedestrians use their ears to judge when to cross nearly as much as their eyes,” he said. “They listen for traffic as well as look, so if you are listening to music or talking on the phone, you are blocking out that vital signal.”

What does StreetBit do with my data?

Hasan runs the UAB SECRETLab, which specializes in digital security, Internet of Things and other uses of technology to solve real-world problems. He read about a previous Schwebel study aimed at distracted pedestrian behavior, Pocket and Walk It, in the eReporter. “I thought it would be the perfect use case for beacon technology,” Hasan said. Because digital security is one of his main research interests, Hasan made user privacy a key focus. The beacons can only communicate with the app in a range of 75–100 feet, he points out, and the app itself doesn’t collect any user data unless it is in the presence of the beacons.

How does it work?

Hasan’s system uses 2.5-inch Bluetooth beacons, which continually transmit signals to detect approaching devices. When they find a participating phone, they wake up Hasan’s custom-built app, which checks to see what’s happening on the device. If the user is listening to music or talking on the phone, the app mutes that audio and plays a recorded warning. If the user’s screen is active (if they are sending a message or watching a video, for instance), a visual warning appears as well.

“When someone is approaching the intersection their phone picks up the signal from the beacons, which triangulate the precise location of the phone,” Hasan explained. Rapid, repeated measurements tell the system whether the person is walking or driving. “There’s no need for warnings if they are driving,” Hasan said.

| “Our previous research shows that pedestrians use their ears to judge when to cross nearly as much as their eyes. They listen for traffic as well as look, so if you are listening to music or talking on the phone, you are blocking out that vital signal.” |

Hasan and several of his graduate students did all the programming for the app. A pilot run in June showed that the system functioned as expected — and that the beacons could stand the difficult conditions of an Alabama summer. “That was one of our biggest concerns,” Hasan said.

Little beacons everywhere

Schwebel envisions a network of inexpensive beacons set up around campus — and perhaps all around Birmingham — if this pilot study proves successful. “I’m excited, but this is also science, so first we have to see how it works,” he said.

To enroll in the trial, send an email to kevin329@uab.edu or call 205-934–4068.

4 easy steps to stay safe as a pedestrian on campus

UAB is committed to fostering a safe and inclusive environment for all Blazers. From mobile apps to bus escort services to B-Alerts and more, make sure you’re up to date on all the ways to stay safer on campus.

UAB is committed to fostering a safe and inclusive environment for all Blazers. From mobile apps to bus escort services to B-Alerts and more, make sure you’re up to date on all the ways to stay safer on campus.