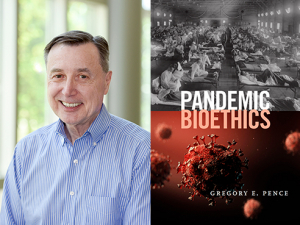

Greg Pence, Ph.D., professor of philosophyNearly everyone knows someone who struggles with addiction, Greg Pence says, whether it’s a partner, family member, friend or colleague.

Greg Pence, Ph.D., professor of philosophyNearly everyone knows someone who struggles with addiction, Greg Pence says, whether it’s a partner, family member, friend or colleague.

National data generally supports Pence’s observation: According to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 14.4 million Americans ages 18 or older have an alcohol-use disorder, while 7.4 million are addicted to illicit drugs. Around 2.5 million American struggle with both.

Pence, a professor of philosophy, has been studying bioethics since the 1970s. His best-selling “Medical Ethics” textbook, now in its 30th year of publication, includes a chapter on alcoholism. That research, combined with a sabbatical spent “reading everything possible about addiction,” served as jumping-off points for his newest book, “Overcoming Addiction: Seven Imperfect Solutions and the End of America’s Greatest Epidemic,” published this month by Rowman and Littlefield. “Overcoming Addiction” explores the billion-dollar industry of addiction treatment and proposes a combination of various treatment approaches, from Alcoholics Anonymous to methadone clinics, to provide a more viable framework for long-term solutions.

“It seemed like there was a need for someone who was impartial and had no skin in the game to survey all the different types of treatment,” Pence said.

Tackling the issues

During his research, Pence says he discovered time and again that while treatments such as Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous have become the “dominant model of how you’re supposed to treat these twin evils,” no formal statistics have been collected to support their efficacy — because the groups do not allow evidence-based evaluations. “Overcoming Addiction” discusses that issue.

“Overcoming Addiction” explores the billion-dollar industry of addiction treatment and proposes a combination of various treatment approaches, from Alcoholics Anonymous to methadone clinics, to provide a more viable framework for long-term solutions.“What evidence there is says that only about 10% of people complete AA or NA programs, and the other 90% leave thinking they are failures,” Pence said.

“Overcoming Addiction” explores the billion-dollar industry of addiction treatment and proposes a combination of various treatment approaches, from Alcoholics Anonymous to methadone clinics, to provide a more viable framework for long-term solutions.“What evidence there is says that only about 10% of people complete AA or NA programs, and the other 90% leave thinking they are failures,” Pence said.

Is the solution, then, in private treatment centers? Pence explores this too in “Overcoming Addiction.” Treatment centers net approximately $40,000 per entrant, he says, making addiction treatment not just societally lucrative, but fiscally so.

“There are people in Florida who, every other month, are spending a month in a $30,000 treatment facility only to go out, use for a month, and then come back,” Pence said. “It’s called the ‘Florida shuffle.’ There’s $32 billion going into treatment in the U.S. It’s just a waterfall of money.”

Many of those treatment centers are staffed by people in recovery themselves and practicing clinicians, which Pence says can be dangerous because it can lead to generalizations that what works for one or some can work for all.

“It’s not true that the same method will work for everyone,” Pence said.

That’s why he is proud of the work being done at UAB’s Collegiate Recovery Community, which promotes and advances students’ personal, academic and professional achievement in pursuit of long-term recovery from addictions and co-occurring mental health disorders, health and well-being and productive engagement in society. The group meets Tuesdays at 7 p.m. at 1102 12th St. South, next to Pita Stop, and hosts special events such as sober tailgating for UAB Football games.

|

“Who am I to give advice? But at least I’m impartial. There’s lots of information people need — people who are desperate to figure out how to help their relative in need, or even themselves.” |

“UAB should be really proud to have created something on campus like this,” Pence said. “We tend to underestimate how many people here might need a place like that.”

New understandings

A major topic covered in “Overcoming Addiction” is what Pence calls “super-pot.” In 1995, cannabis was about 4% THC, which is the chemical that gives the drug its effects; by 2017, that had increased to 17.1% — a nearly 300% increase, NPR reports. Super-pot is a new, high-strength strain of cannabis that has a 80-90% THC strength, made possible by newly concentrated forms such as oil for vaping.

“Growers make hashish, distill it into oil, put it into a vape cartridge and sell it,” Pence said. “It will knock you out with one hit.”

The changes in drug use made possible by vaping has Pence especially concerned. He writes that Big Tobacco “did something evil” getting teenagers and college students addicted to vaping methods such as Juul-ing, because those populations are traditionally much more mentally and emotionally susceptible than adults.

“It was a mass experiment on very vulnerable people, including mentally ill and poor people,” Pence said. “There’s some evidence that the brain doesn’t mature until 25. Between the ages of 15 and 25, we make pretty dumb decisions because we have immature brains and immature characters. It’s dangerous to inject a new, powerful drug into our culture at a very precarious time.”

His solution? Not to prohibit the sale of cannabis products entirely — he does not believe in criminalization of cannabis, he says — but rather to restrict the purchasing age to 25 and cap maximum THC at 25%.

“Most people my age think of pot as harmless, but the new stuff really isn’t, just like vaping isn’t,” Pence said. “The pot my people smoked in college was maybe 2% THC. But there’s big money involved in legalizing super-pot, and they’re going to crush anyone who speaks against them.”

UAB’s Collegiate Recovery Community promotes and advances students’ personal, academic and professional achievement in pursuit of long-term recovery from addictions and co-occurring mental health disorders, health and well-being and productive engagement in society.

UAB’s Collegiate Recovery Community promotes and advances students’ personal, academic and professional achievement in pursuit of long-term recovery from addictions and co-occurring mental health disorders, health and well-being and productive engagement in society.

Hot-button topics

Pence’s views on cannabis and super-pot are not the only controversial subjects in “Overcoming Addiction.” Perhaps more contentious is his idea that alcoholics and addicts do possess some free will over their conditions — a notion that sits in direct conflict with the first of 12 steps for Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous, that alcoholics and addicts are “powerless over alcohol.”

|

“It’s not true that the same method will work for everyone.” |

“If you truly have no control, why not just go to a bar?” Pence asks. “Even some therapists in rehabilitative medicine say that they need people to think they can change. Even though they have a disease, we need them to feel they have control over it.”

Pence studied an idea in neuroscience known as “maturing out” — the idea that around age 35, most alcoholics and addicts will “find themselves making important decisions about whether to throw their lives away on drugs or alcohol or begin to live a normal, adult life,” he writes in “Overcoming Addiction.” This idea has been supported by research but remains provocative, he says, because it can seem like a kind of “medieval philosophy, not scientific.”

“I read about and talked with a lot of people who quit, and almost every person agrees that half the battle in recovery isn’t just physical — it’s also mental,” Pence explained. “The bottom line is that people need individualized treatment. One size is not going to fit all.”

A way forward

Pence’s takes in “Overcoming Addiction” may be divisive, he says — something he is not unfamiliar with. His 1998 “Who’s Afraid of Human Cloning?” offers a candid exploration of arguments for and against human clothing and examines ways in which pop culture has influenced the way people think about the issue.He hopes that the discussions sparked in “Overcoming Addiction” will make people think about the efficacy of various approaches to treatment.“My colleagues were asking me at the time [I published ‘Who’s Afraid of Human Cloning?], ‘Why are you wasting your time writing this? Everyone knows it’s wrong,’” Pence recalled for the UAB Reporter in 2019. “Writing about cloning was scary. But even though I was a voice in the wilderness, I was able to testify before Congress and write more about biotechnology.”

“Who am I to give advice? But at least I’m impartial. There’s lots of information people need — people who are desperate to figure out how to help their relative in need, or even themselves,” Pence said.

Related