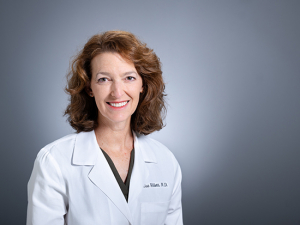

Greg Pence, Ph.D., professor in the College of Arts and Sciences Department of Philosophy and director of the Early Medical School Acceptance ProgramA little more than 40 years ago, Greg Pence took the first step to accept the same advice he now gives his students: Don’t be afraid to take risks.

Greg Pence, Ph.D., professor in the College of Arts and Sciences Department of Philosophy and director of the Early Medical School Acceptance ProgramA little more than 40 years ago, Greg Pence took the first step to accept the same advice he now gives his students: Don’t be afraid to take risks.

Coming to Birmingham was a risk, says Pence, who joined the UAB faculty in 1976 and now is a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences Department of Philosophy. Before that, he earned his master’s degree and doctorate from New York University studying applied ethics with moral philosopher Peter Singer. He then spent two years getting by in Manhattan by working as an adjunct for three separate colleges.

“I needed some luck. I could’ve been someone who never got a regular job,” he said. “I left Manhattan to come here.”

Besides the obvious — that 1970s Birmingham was an entirely different experience culturally from 1970s New York City, a gritty and turbulent place gripped by crime and fiscal crises — Pence made a decision that would influence the rest of his career and propel him into the national spotlight on more than one occasion: He transitioned from studying philosophy to studying bioethics, or the intersection of the ethics of medical and biological research.

“To keep a job, I had to jump out from one and into the other,” he said. “When I got hired to teach medical ethics, I had to do [clinical] rounds for a few months in the medical center. I yearned to be safe in a philosophy classroom.”

‘Different administrative hats’

In Pence’s first years at UAB, he taught a medical ethics course in the School of Medicine, something he would continue to do for the coming three decades. A good number of those early students now are on faculty at UAB, Pence says, a fact of which he is proud. Simultaneously, he was instrumental in developing the ethics program in the Department of Philosophy, for which he also served as chair (2012-2018). In addition, Pence coached the UAB Ethics Bowl Team, which won the national championship in 2010, and continues to coach the UAB Bioethics Bowl Team, which won national championships in 2011, 2016 and again in April of this year.

|

“When I got hired to teach medical ethics, I had to do [clinical] rounds for a few months in the medical center. I yearned to be safe in a philosophy classroom.” |

He also directs UAB’s Early Medical School Acceptance Program (EMSAP), an undergraduate and medical school educational program that provides highly qualified students an enriched undergraduate experience in preparation for medical, dental or optometry school. EMSAP students take two courses with Pence, one in bioethics and the other in narrative medicine.

Though his work in the department and with EMSAP, Pence says he’s required to wear two different administrative hats, but the reward is interacting with 50 or so “high-achieving, wonderful and intense students.”

“They’re kind of my secret weapon,” he said. “They’re always pushing me to learn.”

This year, Pence received the Ireland Prize for Scholarly Distinction, presented by the UAB College of Arts and Sciences to a full-time faculty member for professional and academic achievements and contributions to the university and local community. He also has won both Ellen Gregg Ingalls/UAB National Alumni Society Award for Lifetime Achievement in Teaching and the President’s Award for Excellence and Achievement.

“I admire previous winners of this award and am pleased that they’ve chosen me,” Pence told UAB News. One of those previous winners was previous philosophy Chair and College of Arts and Sciences Dean James Rachels, Ph.D., who was the second recipient of the Ireland Prize. “Coming after 43 years at UAB, it’s gratifying.”

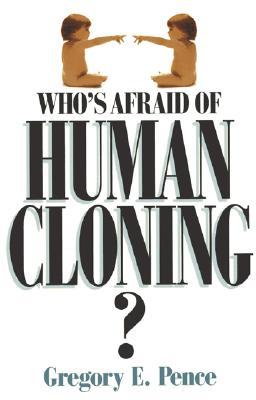

Pence's 1998 “Whose Afraid of Human Cloning?” offers a candid exploration of arguments for and against human clothing and examines ways in which pop culture has influenced the way people think about the issue.Something to teach

Pence's 1998 “Whose Afraid of Human Cloning?” offers a candid exploration of arguments for and against human clothing and examines ways in which pop culture has influenced the way people think about the issue.Something to teach

“I asked my students whether or not a human life was worth at least $5.”

So begins an op-ed penned by Pence for the Dec. 4, 1974, edition of the New York Times, written during those years working as a part-time instructor for colleges across New York City. That opinion article was one of the first steps on Pence’s journey to becoming a respected ethics scholar.

Perhaps Pence’s most influential work is his best-selling “Medical Ethics” textbook, which is approaching its 30th year of publication. The book explores “people making choices and learning from their mistakes,” Pence says, and includes discussion of some of the most famous bioethics cases and their issues, such as Terri Schiavo’s right-to-die legal case that stretched from 1990 to 2005. It’s now been translated into Japanese and Korean. Writing it was, in many ways, a risk, Pence says. The desire to do so was born out of necessity, not necessarily ambition.

“When I started at UAB, there were no textbooks [in the field of medical ethics],” he said. “I wrote it to have something to teach — but it did bring a sense of accomplishment.”

However, Pence says it’s his trade books that are perhaps the most recognizable. His 1998 “Who's Afraid of Human Cloning?” offers a candid exploration of arguments for and against human clothing and examines ways in which pop culture has influenced the way people think about the issue. In 2001, Pence testified before Congress against a bill that would have criminalized all aspects of human cloning. All total, he has authored more than 10 books and 70-plus op-eds discussing issues in medical ethics, from Dolly, a sheep who was the first mammal cloned from an adult somatic cell, to the safety of genetically modified foods.

|

“Being interested in bioethics might be a lifelong interest. Everything is new every year. We had cloning, and now we have CRISPR.” |

“My colleagues were asking me at the time [I published ‘Who's Afraid of Human Cloning?], ‘Why are you wasting your time writing this? Everyone knows it’s wrong,’” Pence recalled. “Writing about cloning was scary. But even though I was a voice in the wilderness, I was able to testify before Congress and write more about biotechnology.”

A lifelong interest

In 1975, journalist Larry Altman reported in the New York Times that effective flood control in India could effectively eradicate cholera and typhoid fever from the country, essentially ending the field of infectious diseases. Just a short six years later, in 1981, the Centers for Disease Control published an article in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, describing cases of a rare lung infection in five young, white, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles — information that began a domino effect that would twist and morph into the AIDS crisis. Then came other epidemiological crises, such as the Zika and Ebola viruses. It’s this ebb and flow that, to Pence, makes bioethics the most exciting subject being taught in college right now.

Pence says he encourages his students, especially those in EMSAP, to consider studying bioethics because of the tools it provides in terms of thinking about the world.

“Being interested in bioethics might be a lifelong interest,” he said, noting that it has certainly become so for him. “Everything is new every year. We had cloning, and now we have CRISPR.”