The key to being a responsible news consumer is understanding the relationship between science and uncertainty, says Kevin McCain, Ph.D., associate professor of philosophy. This is especially true during a pandemic in which scientists work around the clock to make cutting-edge discoveries, media outlets provide updates 24/7 and social media circulates information, accurate or otherwise, at breakneck speed.

In his book, “Uncertainty: How It Makes Science Advance,” published this past year by Oxford University Press, McCain argues that uncertainty can fuel scientific endeavors, leading to more and better discoveries and understanding. But what happens when misinterpretations of that uncertainty go public? Combatting the consequences of misunderstanding the realities of scientific discoveries is tricky, McCain says, but it can be done.

“It’s common for people to think of science or scientific knowledge as something that’s known with certainty,” he explained. “So, we often hear things like ‘science has proven that…’ or ‘science says this, so this is certain.’

“Relatedly, we see people being skeptical of calling something science or accepting something as scientific knowledge when the fact in question isn’t known with certainty. This, I think, is a misunderstanding of both the nature of science and the relationship between knowledge and certainty.”

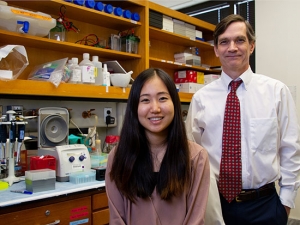

Kevin McCain, Ph.D., associate professor of philosophyConsider the gray areas

Kevin McCain, Ph.D., associate professor of philosophyConsider the gray areas

McCain says understanding that relationship is rooted in understanding two ideas of certainty. Beware the pitfall of unwarranted psychological certainty, he warns — being absolutely sure that something is true without sufficient evidence. Psychological certainty, which simply has to do with how firmly someone believes, isn’t the sort of certainty that is relevant for determining whether something counts as scientific knowledge, he says, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t widespread.

“It’s not uncommon to encounter people being absolutely certain that something is true, despite knowing very little about the topic and having very little relevant information,” he said. “Psychological certainty is simply a matter of one’s strength of conviction.”

For example, McCain says someone might be psychologically certain that they are immune to COVID-19 because their horoscope predicted a year of good health.

“This is a clear case where the person’s level of confidence in a claim is out of touch with the evidence they have,” he continued.

The mirror image of psychological certainty is what McCain refers to as epistemic certainty — this type of certainty is the upper limit of evidential support. And, it is evidence and evidential support relations that inform knowledge and science, he says.

“To be epistemically certain of some fact requires having evidence such that there’s absolutely no possible way you could be wrong — and possible here is meant in the broadest sense of the term.”

Understanding epistemic certainty requires accepting the existence of a gray area. Did you really write that email, he asks? Did you really read the recipient’s reply? After all, he says, you can’t be epistemically certain — “there’s a miniscule chance you’re having a hallucination or something even crazier,” he posits. But it’s obvious that you know you wrote the email, and you know you read the reply. So what does that mean? Essentially, it means that epistemic certainty can’t be required for knowledge, even though most people think exactly the opposite.

A big piece of the puzzle is implementing rationality — matching our level of psychological certainty to our epistemic certainty. |

“We can know things without being epistemically certain — this is true in ordinary life, and it’s true in science,” McCain said. “Often people think science gives us epistemic certainty, which is a mistake, because we can’t have that kind of certainty when it comes to pretty much any fact about the world around us.”

Therein lies the rub, he continues:

“When someone learns that a particular scientific claim isn’t epistemically certain — which is true of all scientific claims — they might question whether it’s really science at all or think that it doesn’t need to be taken seriously, and so on.”

Take the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, for example. When COVID-19 first came to the United States, many people chose to ignore warnings and failed to engage in proper social distancing — think the spring-breakers that made national news, McCain says. They were likely interpreting uncertainty in data about risk and contraction to mean that “the coronavirus wasn’t something that needed to be taken seriously.” This is a common mistake, he warns.

“This is the sort of mistake that people make when they tend to expect certainty from science, and so fail to appreciate that legitimate science always has uncertainties,” McCain said. “People who make this mistake tend to think that if a model or scientific finding is uncertain, it’s not really science.”

“For non-scientists like myself, I think the thing to do is listen carefully to what the experts are telling us and make informed decisions based upon that evidence.”

But be careful of the pendulum swing, he says: Overlooking uncertainty and a lack of evidence in favor of blind belief is not the answer, either.

“There are people who are downplaying uncertainties when it comes to potential treatments for those infected with the virus,” he said. “Some are taking anecdotal evidence from a few recoveries to be rock-solid evidence of the effectiveness of particular treatments.”

An example of this, McCain continues, is the rash of people who, hoping to prevent contracting COVID-19, ingested or injected disinfectants, despite the “tremendous evidence that drinking bleach and injecting Lysol are horrible ideas.” Another example might be someone drinking several glasses of orange juice the day after being diagnosed with coronavirus and recovering within a few days — some might think drinking orange juice can have an effect on the virus itself.

In his book, “Uncertainty: How It Makes Science Advance,” published this past year by Oxford University Press, McCain argues that uncertainty can fuel scientific endeavors, leading to more and better discoveries and understanding.“Of course, this overlooks legitimate uncertainties,” McCain said. “Did this person really have COVID-19 and recover at all? Did the orange juice have anything to do with it? The fact that one person drank orange juice and recovered quickly — granting their story is legitimate — gives us very little evidence that orange juice helps fight COVID-19.

In his book, “Uncertainty: How It Makes Science Advance,” published this past year by Oxford University Press, McCain argues that uncertainty can fuel scientific endeavors, leading to more and better discoveries and understanding.“Of course, this overlooks legitimate uncertainties,” McCain said. “Did this person really have COVID-19 and recover at all? Did the orange juice have anything to do with it? The fact that one person drank orange juice and recovered quickly — granting their story is legitimate — gives us very little evidence that orange juice helps fight COVID-19.

“Unfortunately, people will often jump at such anecdotal evidence and take it to be strong support.”

Where scientists step in

Those who categorically “do” science are the first to recognize the uncertainties that come with it, McCain continues. In most research, the goals are to disprove what is called the null hypothesis, which claims that between two tests, there is no difference, and prove the alternate hypothesis, which says there is. For example: if a small-business owner buys a billboard advertising their burger joint and wonders whether it increased visitor numbers, the null hypothesis would be that the billboard did not bring in additional customers, while the alternate hypothesis would state that it did. The p-value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true.

Researchers who publish findings include the p-value to reflect the innate uncertainty that comes with scientific research.

“In order for findings to be significant, the p-value has to be very small — but it doesn’t have to be zero,” McCain said.

Practice uncertainty responsibly

“Science is uncertain, but I wouldn’t advise betting against it.” |

It’s important to realize that all the knowledge possessed about the world around us contains at least some level of uncertainty, McCain explains, and that realization can protect against being misled by people who desire to cast doubt wrongly on scientific findings. A big piece of that puzzle, he continues, is implementing rationality — matching our level of psychological certainty to our epistemic certainty.

“We should be less confident of claims that are weakly supported by the evidence and more confident of claims that are strongly supported,” he explained.

While no person, scientist or otherwise, can claim 100% epistemic certainty about pretty much anything, we have much stronger evidence about some things than others, he continues. For example, there is good evidence to support the idea that social distancing can reduce the spread of coronavirus — “the evidence is so good that it would be irrational not to believe it helps,” McCain said.

“We can know things despite lacking certainty, and we can definitely act rationally by accepting well-supported findings,” McCain said. “Recognizing that science is uncertain helps us avoid being led astray when someone points out the uncertainties in particular scientific findings.

“We can know things despite lacking certainty, and we can definitely act rationally by accepting well-supported findings. Recognizing that science is uncertain helps us avoid being led astray when someone points out the uncertainties in particular scientific findings.”

“For instance, it’s not certain that if I walk out in front of a moving bus that I’ll be struck and severely injured or killed — after all, some people hit by buses are unharmed. However, the rational decision is clearly to not walk in front of a moving bus.”

But uncertainty about social distancing’s efficacy can be exacerbated by other questions surrounding coronavirus: who and how many people are infected by or carrying the virus, how to balance social distancing with its costs, economic and otherwise, and the efficacy of current testing solutions. Again, McCain says taking personal responsibility to seek out well-supported findings touted by infectious disease experts and epidemiologists is the best way to combat uncertainty.

“We can know things without being epistemically certain — this is true in ordinary life, and it’s true in science.” |

“For non-scientists like myself, I think the thing to do is listen carefully to what the experts are telling us and make informed decisions based upon that evidence,” he explained. “We avoid believing, and hopefully acting, irresponsibly by getting evidence from trusted sources and remembering that scientific experts are often aware of evidence the average person isn’t and are better at evaluating evidence than the average person, so their testimony itself is strong evidence.

“At the end of the day, will we be able to be certain that we’re making the best choice? No, because as I mentioned, even the best science is epistemically uncertain, but that doesn’t make it untrustworthy. Going with the best scientific evidence available is definitely the rational way for us to proceed.

“After all, science is uncertain, but I wouldn’t advise betting against it.”