In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, UAB Medicine canceled all elective surgeries and interventional procedures in mid-March; all clinics moved to an essential-care-only policy and in-office visits converted to eMedicine telemedicine appointments, by video or telephone. During the next few weeks, physicians began interacting with patients in an entirely new way. In March, prior to the cancellation of most in-office visits, there were only three video appointments per day, on average. On April 29 alone, UAB physicians saw 1,400 patients by video. "The prominence of telehealth will undoubtedly continue to grow even after we conquer COVID-19," said School of Medicine Dean Selwyn Vickers, M.D., recently. "Not only does it help control health care costs, but it also expands much-needed patient care and subspecialty access to rural and underserved areas."

Peter King, M.D., professor and vice chair in the Department of Neurology, and director of the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic in the Birmingham VA Medical Center, wrote the following account of his experience entering this new world of telemedicine.

Peter King, M.D., in his office, as seen through the VA Medical Center's telehealth portal (with his nurse practitioner, Kim Redwine, inset).I learned the importance — and power — of a physician’s touch when I assisted my father, who was a physician in a small town in Ohio. He saw patients of all ages in the office and would do house calls for those who couldn’t make it in. Dad’s gentle touch and sense of humor put even the most frightened patients at ease. It was a powerful lesson and one that was deeply imprinted in my medical psyche.

Peter King, M.D., in his office, as seen through the VA Medical Center's telehealth portal (with his nurse practitioner, Kim Redwine, inset).I learned the importance — and power — of a physician’s touch when I assisted my father, who was a physician in a small town in Ohio. He saw patients of all ages in the office and would do house calls for those who couldn’t make it in. Dad’s gentle touch and sense of humor put even the most frightened patients at ease. It was a powerful lesson and one that was deeply imprinted in my medical psyche.

Needless to say, the accelerated transition to virtual medicine by the COVID-19 pandemic struck a dissonant chord deep inside me. While brave first-responders were caring for infected patients, there was a simultaneous upheaval in the underbelly of health care. For the safety of everyone, we providers had no choice but to convert immediately all of our in-person clinics to virtual ones. Even insurance companies endorsed this change by altering rules of reimbursement.

Like a slap in the face, this new reality forced us to change our approach to patient care overnight (versus the gradual transition that was occurring prior to the pandemic). All providers had to learn new tricks quickly, but that created stress on older docs like me who are less adept at online video communication. Moreover, as a neuromuscular specialist, the physical exam remains an important component of my evaluation, and technology has not advanced far enough to do it remotely (like using a reflex hammer to make the leg kick).

So I had no choice but to jump in and learn. With the help of younger providers, I was able to hold my first virtual clinic of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). For those not familiar with ALS, it is a severely debilitating and incurable disease that requires extensive and ongoing care. In my mind it ranks at or near the top of diseases where the physician’s touch can provide comfort to patients and reassurance that they are not alone.

With some trepidation, I tuned into the first patient, who was a young veteran newly diagnosed with ALS. He was in his bedroom and I was at my home. I was thinking of this bizarre arrangement and had to chuckle that health care has come full circle back to house calls — except that we were 90 miles apart!

Read more: |

After getting an update from this patient, I needed to gauge how much weaker he had gotten by performing a physical exam. Improvising, I solicited the help of his brother and instructed him on the different components of the motor exam while I watched by video. We were able to angle his camera so I could test legs and arms, and this provided me with enough information to make several medical decisions. Success! Although I could not touch the patient, I was able to look at him and tell him I cared — ironically, in a more effective and less intimidating way than in person, where I would be wearing a mask.

After completing the visit, I could feel my skepticism waning along with fears of breaching my internal code of patient care. As I see more patients virtually, I have awakened to the many benefits. Patients are more at ease at home, and for those with mobility limitations it removes the burden of travel and the associated risk of injury. For many, it could mean the difference between getting health care or not.

Virtual medicine will not replace in-person visits, as there are many diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be done at a distance — yet. However, one silver lining to the very dark COVID-19 cloud is that it has provided a catalyst for virtual medicine. It has forced us all to learn new tricks that will enhance our delivery of care to patients. More important, we are learning that a virtual touch can be as effective as a physical one.

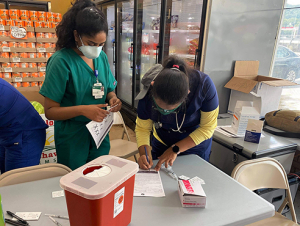

The student-led group partnered with the Alabama Statewide Area Health Education Centers program to distribute Pfizer vaccine doses.

The student-led group partnered with the Alabama Statewide Area Health Education Centers program to distribute Pfizer vaccine doses.

Fifteen students helped sort and prep donated items and distribute them at the Gardendale Civic Center drive-thru.

Fifteen students helped sort and prep donated items and distribute them at the Gardendale Civic Center drive-thru.

UAB’s ability to recruit employees worldwide adds promotes diversity in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Meet these five families featured in the paper’s Jan. 15 issue of the “

UAB’s ability to recruit employees worldwide adds promotes diversity in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Meet these five families featured in the paper’s Jan. 15 issue of the “