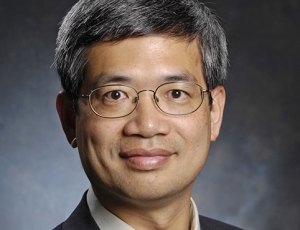

Bianca Godwins, UAB medical student and MBA candidate, manages a team of up to 70 undergraduate, graduate and medical students working as contact-tracers as part of a contract between the School of Public Health and the Alabama Department of Public Health.By the time Madelyn Wild gets the number, the clock is already ticking. At the other end of the line is someone who has just been diagnosed with COVID-19, whether they know it or not. As the phone starts to ring, she has no idea whether that person will be terrified, grateful or convinced that the entire pandemic is a hoax. Still, guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) specify that each new case should be notified in fewer than 24 hours, and she has a long list to get through.

Bianca Godwins, UAB medical student and MBA candidate, manages a team of up to 70 undergraduate, graduate and medical students working as contact-tracers as part of a contract between the School of Public Health and the Alabama Department of Public Health.By the time Madelyn Wild gets the number, the clock is already ticking. At the other end of the line is someone who has just been diagnosed with COVID-19, whether they know it or not. As the phone starts to ring, she has no idea whether that person will be terrified, grateful or convinced that the entire pandemic is a hoax. Still, guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) specify that each new case should be notified in fewer than 24 hours, and she has a long list to get through.

Wild is a senior majoring in public health at UAB. She also is a contact-tracer for the School of Public Health, which has a contract with the Alabama Department of Health (ADPH) to assist in this crucial work. Each shift, she gets a new list of numbers to call. "No shift is the same," Wild said. "Some days are very slow and frustrating. And I've definitely had my fair share of rude people." But "I have had many other cases who have made me smile," she added, and "I've been told several times what a blessing it is that we at the ADPH are taking the time to look out for everyone else's health. I am always eager to see what each of my new cases are like."

Wild is one of dozens of students participating in UAB's contact-tracing efforts. Employees of UAB's Survey Research Unit, who communicate with participants in large UAB studies such as the REGARDS stroke trial, are also doing contact-tracing. Both groups are under the direction of Andrew Rucks, Ph.D., professor emeritus in the Department of Health Care Organization and Policy.

‘It saves lives’

"We have worked on thousands of cases," said Bianca Godwins, a second-year student in the School of Medicine and Collat School of Business. Godwins is one of two managers responsible for overseeing up to 70 UAB undergraduate, graduate and medical students who act as case investigators. "For the patient it may seem intrusive or annoying to be asked to share their experiences, but it really is so important," Godwins said. "It does truly save lives. When we let a patient know how long they need to stay in quarantine — and if that person follows through — that can represent hundreds of people saved from having to be exposed to COVID — either saving their lives directly or at least saving them from having to undergo such a traumatizing ailment."

Like her fellow contact-tracers, Claudia Datnow-Martinez — a senior in UAB’s Accelerated Bachelor’s to Master of Public Health program who is minoring in Spanish — has had her share of frustrating exchanges. “There are patients who think we are trying to scam them, and there have been scammers who have posed as ADPH or UAB employees and asked inappropriate questions,” she said. But the “patients who are really nice and understanding and kind make my day. For me, one of the best experiences has been to help the Spanish-speaking patients. Because of the language barrier, they may not be as informed. Some want to know, ‘How did I get this?’ and ‘How can I get better?’ I can explain things to them, like the importance of wearing their face masks and covering their coughs.”

Random sampling

Claudia Datnow-Martinez, a senior majoring in public health, has been able to use her language skills to help Spanish-speaking patients. "I can explain things to them, like the importance of wearing their face masks and covering their coughs," she said.Wild got connected with contact-tracing through a professor in the School of Public Health. "Over the summer I had taken a course focused on population health and COVID-19," she said. "As part of the course we all completed an online contact-tracing certificate with Johns Hopkins University. After that, my professor had been in contact with the health department about the contact-tracing program and I was recommended to participate." Datnow-Martinez turned to contact-tracing after her job in a research lab was cut because of pandemic-induced budget cuts.

Claudia Datnow-Martinez, a senior majoring in public health, has been able to use her language skills to help Spanish-speaking patients. "I can explain things to them, like the importance of wearing their face masks and covering their coughs," she said.Wild got connected with contact-tracing through a professor in the School of Public Health. "Over the summer I had taken a course focused on population health and COVID-19," she said. "As part of the course we all completed an online contact-tracing certificate with Johns Hopkins University. After that, my professor had been in contact with the health department about the contact-tracing program and I was recommended to participate." Datnow-Martinez turned to contact-tracing after her job in a research lab was cut because of pandemic-induced budget cuts.

Godwins got involved when "the School of Public Health reached out to the School of Medicine to ask if any students were interested in taking part," she said. Phillip Braswell, who graduated from the School of Medicine this summer, did the same. "When I heard about the opportunity to work with ADPH, I immediately signed up," he said. "Contact-tracing is one of the most important public health tools we have to slow the spread of a disease like COVID-19, and I felt like it was my duty to be a part of that.”

The response was so great that the schools had to use a random number-generator to select the students who would take part as case investigators/contact-tracers and to choose the lead investigators. "I was randomly chosen to be a lead investigator,” Godwins said with a laugh, “only to be promoted to a project manager for the students a short while after.”

She seems like a natural choice for the job. Godwins is the president of the School of Medicine’s chapter of the American Medical Women’s Association and is pursuing a joint M.D./MBA because "I see from a systemic perspective how many gaps and inconsistencies there are in our health care system," she said. "By combining clinical knowledge and managerial knowledge, I will be able to help fill those gaps and develop needed connections between physicians and health care executives — all for our future patients." Plus, she is naturally suited to the contact-tracing role, Godwins added: "I love to talk."

A typical shift

Unfortunately, there are so many conversations to have. "Our running trend is probably 4,000 or so cases each month," Godwins said.

The students all work remotely, using a laptop and telephone headset. Shifts are designed to fit around student schedules, Godwins said. For instance, "med students primarily work 5-9 p.m. on weekdays and on weekends," when it may be easier to reach people who are at their jobs during the day.

Some patients, like Godwins, love to talk. Many do not. "Our calls range 30-45 minutes down to zero minutes if someone is not willing to talk,” she said. “We get that all the time, unfortunately, partly because there are scammers who have taken advantage of the situation and used it prey on people. Some aren't surprised; others are super-afraid. They may be experiencing symptoms but can't get off of work."

If the patient was tested by their care provider, they already know they have tested positive. People who have been tested at a community drive or event may be hearing the news of their diagnosis for the first time. Either way, "we contact each one and provide them with information on health precautions and isolation," Godwins said.

Then the tracers ask the person about where they have been and the people they have been in close contact with during the past two weeks. "We let them know this information won't be shared with anyone else, except their employer if they need to be notified, although the patient will be left anonymous," Godwins said. "We ask for their recent contacts and contact those contacts." These contacts are told they have been exposed to someone with a laboratory-diagnosed case of COVID-19, but contact-tracers do not reveal the person’s name. After each call is done, Godwins said, "we take all that information and put it in the ALNBS system for ADPH, and then they send that to the CDC."

Common questions

"I often get asked, 'How long will my symptoms last?' and 'Will I get this again?'" Braswell said. "Unfortunately, many of the answers we have for patients are ambiguous. I try to lean on what I am hearing from other patients and the latest research to inform people of the most up-to-date and accurate information. However, I always give a caveat that we are dealing with a new disease and are learning more every day."

"Many of the people who have tested positive do not actually know how long their isolation period should be," Wild said. "Also, I am commonly asked if it is necessary to get retested before leaving isolation.” The answer? “It is not required if you have completed your 10-day isolation and your symptoms are gone,” Wild said. “But I have had many people tell me that they need to get retested before they can return to work." Several patients have "confided in me about non-compliance at their work and how scared and frustrated they are," Wild said. "I do everything in my power to reach out to a higher authority when necessary, but I can't help but feel angry for these people as well."

Ultimately, many people want to ask the most basic question: Why are you calling me? “You would be surprised how few people know what contact-tracing is,” Datnow-Martinez said. “We hear about it a lot at UAB, but we are usually calling people in rural or more isolated areas.” (Jefferson County and Mobile County have their own departments of health that handle contact-tracing.)

Hearing the distress in patients’ voices, and seeing first-hand how often those patients are people of color, has convinced Datnow-Martinez to refocus her career plans. “Before COVID, my research interest was contraceptive use in women, but now that has shifted to the huge disparities in Black and Hispanic populations that COVID has brought to light,” she said. “There is a lot of work to be done in our health system.”

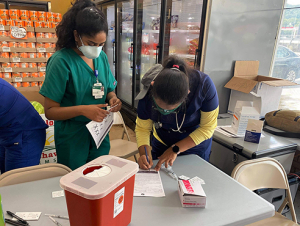

The student-led group partnered with the Alabama Statewide Area Health Education Centers program to distribute Pfizer vaccine doses.

The student-led group partnered with the Alabama Statewide Area Health Education Centers program to distribute Pfizer vaccine doses.

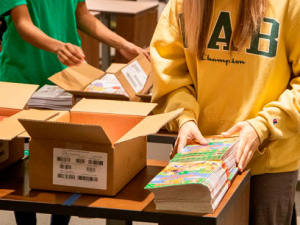

Fifteen students helped sort and prep donated items and distribute them at the Gardendale Civic Center drive-thru.

Fifteen students helped sort and prep donated items and distribute them at the Gardendale Civic Center drive-thru.

UAB’s ability to recruit employees worldwide adds promotes diversity in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Meet these five families featured in the paper’s Jan. 15 issue of the “

UAB’s ability to recruit employees worldwide adds promotes diversity in Birmingham and surrounding areas. Meet these five families featured in the paper’s Jan. 15 issue of the “