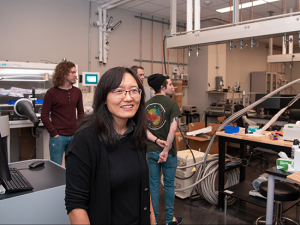

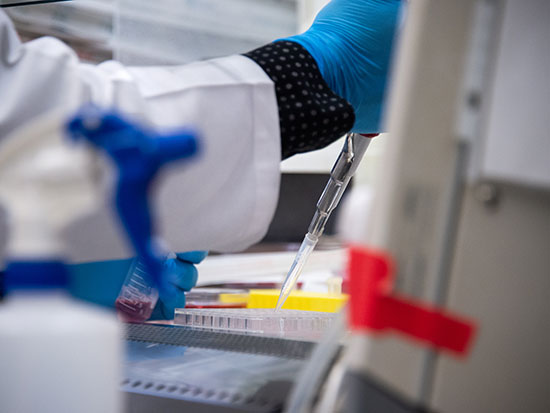

As Phase I of UAB's reentry plan moves forward, some of the first scientists to return to the lab explain how they are adapting. LEXI COON / University RelationsFantastic. Excited. Liberated. As the first wave of researchers began to return to their labs in Phase I of UAB’s reentry plan May 26, the adjectives they used varied, but the overwhelming feeling can be captured in a three-letter noun: joy.

As Phase I of UAB's reentry plan moves forward, some of the first scientists to return to the lab explain how they are adapting. LEXI COON / University RelationsFantastic. Excited. Liberated. As the first wave of researchers began to return to their labs in Phase I of UAB’s reentry plan May 26, the adjectives they used varied, but the overwhelming feeling can be captured in a three-letter noun: joy.

“Just the fact that we get to come to the lab is mentally a complete game changer,” said Associate Professor Karolina Mukhtar, Ph.D., associate chair in the Department of Biology, who studies immune defense mechanisms in plants.

“It’s fantastic to be back up and running,” said Professor Craig Powell, Ph.D., an autism researcher and the Virginia B. Spencer Endowed Chair in the Department of Neurobiology and director of the Civitan International Research Center at UAB. “Everyone was excited to get back and to make new progress. There are only so much data to analyze and graph.”

“For those of us who are experimentalists and used to being in the lab, that’s our happy place,” said Lori McMahon, Ph.D., dean of the Graduate School and professor in the Department of Cell, Developmental and Integrative Biology who studies Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other neurological disorders.

| “For those of us who are experimentalists and used to being in the lab, that’s our happy place…. Doing experiments is very therapeutic, particularly right now being in the middle of a pandemic. When you’re in the lab doing experiments, that’s the only thing that matters — that sense of discovery.” |

“I feel that, and my students have been telling me that. Doing experiments is very therapeutic, particularly right now being in the middle of a pandemic. When you’re in the lab doing experiments, that’s the only thing that matters — that sense of discovery.”

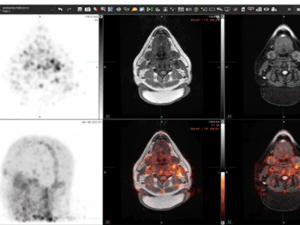

In order to return, all principal investigators were required to submit a detailed operational plan to the Office of Research. McMahon, Powell and Mukhtar — along with Lee Moradi, Ph.D., whose Engineering and Innovative Technology Development group has worked throughout the shutdown in order to maintain essential equipment on the International Space Station — shared how they navigated that process, and how they have adapted their labs to the demands of COVID–19. Here is their advice:

1. Make sure everyone knows the plan…

“We spent a lot of time preparing,” McMahon said. “We have our lab meetings on Fridays from 3–5. We moved those to Zoom during the shutdown, and we spent parts of four lab meetings in May, when we knew that research was going to reopen, discussing how we would manage our schedules, social-distance, share equipment and everything else. That preparation was key. I’ve gotten a lot of messages from my students and other students saying, ‘Thank you, I feel safe, I feel comfortable, I know what’s expected and what to do.’”

Karolina Mukhtar, Ph.D.

What she's working on now:

“We need our plants to be at least two weeks old when we start working with them. We are still at the stage where they have been sown and daily now someone is looking at whether they are doing well. In the meantime, there were things that were frozen — RNA, leaf samples, proteins — that we have thawed and are beginning to work with.”

2. …and everyone has a chance to contribute

“The absolute key advice I have is for faculty to involve their lab members in their planning,” McMahon said. “I think that’s what helped my lab feel confident, secure and understand the decisions we were making. I had a diagram of our lab footprint, showing where all the benches are, and I shared it on Zoom and we color-coded areas and talked through schedules and what would work best for them — if we needed to move equipment, which doors we would use to enter and exit, and so on. They really appreciated that and I think all lab members would appreciate having their PI or mentor give them an opportunity for input. They spend more time working in the lab than the faculty, so getting their input and perspective is essential.”

Lori McMahon, Ph.D.

What she's working on now:

“We have restarted every one of our projects. We have an Alzheimer’s disease project that really stopped. We had approval for two students to come into the lab periodically to do experiments. Our Parkinson’s disease collaboration with Matt Goldberg and a dystonia project with David Standaert [both in the Department of Neurology] — all of those are ramping up now.”

3. Talk, talk, talk — however you decide to do it

“There are always people in science who are focused on their own things and living in their own world,” Mukhtar said. “Now, we can’t afford that. We’ve set up a Google Hangout group — a lot of labs are using Slack, too — so we can communicate about everything. We’re going by the rule that you cannot overcommunicate. My lab is encouraged to send an instant message to the whole group to make sure everyone is on the same page: ‘At 10 a.m. I am planning to use this instrument: Is that ok with everyone?’ And if you aren’t going to be able to come in for your shift, tell everyone. There will be people who would love to have it.”

“We made a Google Calendar, and we have all of our workstations listed there,” McMahon said. “Every lab member can log on and see who is in the lab and who is using which equipment at what time. We do a lot of brain slices in our lab and that requires a vibratome. Typically that’s a bottleneck and people would just hang around it and use it when it was free. Now all lab members can adjust their time so they come right in and use that piece of equipment.”

Craig Powell, Ph.D.

What he's working on now:

“Our lab depends on mouse genetic models of autism for everything that we do. Fortunately, thanks to the amazing efforts of Sam Cartner and his animal husbandry teams, we were able to continue our essential mouse breeding [during the limited business model] while stopping the less essential breeding. So now we have a cache of experimental animals to work with to perform actual experiments almost right away.”

4. Start slow

“The new reality is something none of us have ever experienced, and there are no magic solutions,” said Moradi, who is director of the Engineering and Innovative Technology Development group and professor and interim chair of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. “My advice is to start slow. As your on-campus work ramps up, your staff and researchers begin to adapt to the new reality and they will find innovative ways to be safe while getting their work done. Innovation and adaptation is key, not frustration and rush to action or judgment.”

| See a list of frequently asked questions about the resumption of research operations and download operational plan templates. |

Out of 40 EITD employees, 16 stayed on campus throughout the limited business model period in two shifts of eight people. “We only experienced a drop in work efficiency during the first month of the shutdown, but over time, we have been able to adapt and return to normal efficiency,” Moradi said. “The first shift was from 5 a.m. to 1 p.m. and the second shift was from 1 p.m. to 9 p.m.,” he explained. “Those were surreal times because when we drove to work, the roads to campus and the streets on campus were desolate.”

When UAB moved into the first phase of re-entry May 26, “we increased our on-campus population from 16 to 24, over the same two shifts,” Moradi said. “Under the guidance of the VPR’s office and UAB COVID–19 health directives, we wear PPEs, practice safe distancing and abide by all recommendations. We have not had any health problems.

“All EITD employees that come to campus have gone through the UAB online training and received their certificates,” Moradi said. “They also submit their online health check every three days. As an organization of 40 employees, we have weekly Zoom meetings and daily project meetings via Zoom. We avoid in-person meetings at all costs and wear masks and keep a distance of six feet if we meet in person. We wear masks in all common areas except our single offices. We practice the same routines in the labs and try to keep the occupancy of each lab to a maximum of two employees.”

Lee Moradi, Ph.D.

What he's working on now:

“NASA submitted a letter to UAB [at the outset of the limited business model] declaring EITD ‘mission essential’ for the International Space Station science programs. We have always loved to be on campus and our work, which is building hardware for the ISS, cannot be done remotely. We have to be in the lab manufacturing, assembling and testing the hardware to be flown on almost all missions to the ISS.”

5. Get out your spray bottle

“Since we are plant people, our first step in coming back is to grow the plants,” Mukhtar said. But even before that, “the first order of business was rolling up our sleeves and cleaning,” she said. “This takes nothing away from our amazing Facilities team, but when spaces and equipment have been idle for months, they gather dust. We study plant immune responses, so any traces of contaminants can potentially ruin our work. To start our work right, we needed to scrub the greenhouse, growth chambers, everything. No one enjoys cleaning, but for the first few days most of the shifts basically consisted of people scrubbing and bleaching.” That will continue — “cleaning the space, every piece of equipment, after each use,” Mukhtar said. “We use ethanol and paper wipes. That’s the most effective way of doing it.”

McMahon’s lab manager went to a dollar store and bought small spray bottles for every person in the lab. “They all have their own little bottles of 70% ethanol to keep in one pocket of their lab coat and paper towels in the other,” McMahon said. “They have them in the lab but also when they go to the bathroom or ice machine or wherever. That helps them always feel protected. That’s probably a habit we will continue, even after the pandemic is over.”

6. Be flexible with space — and time

“We have gotten people out of their usual workstations to help accommodate social distancing — that’s one adjustment everyone had to deal with,” Mukhtar said. “A bench is just a bench - it’s not John’s or Karolina’s. We’ve become more integrated in that way.” The change can be hard, she recognizes. “People get very attached,” Mukhtar said. “You spend years of your life in this little space. It would have been easy for someone to think, ‘Now I’m not on my bench and it’s a tragedy,’ but people have been very reasonable.”

| “We have gotten people out of their usual workstations to help accommodate social distancing — that’s one adjustment everyone had to deal with. A bench is just a bench - it’s not John’s or Karolina’s. We’ve become more integrated in that way.” |

“I think the hardest part is accepting the fact that not everyone can work at the same time,” Powell said. “We have separated desk spaces, have only one person per lab bay, constructed makeshift barriers between adjacent benches and moved to two staggered shifts each day. This means that we have only three people in the lab at any given time.”

Lab members need to adjust to different schedules and ways of working. “So much of our work day is spent planning experiments,” Powell said. “If people can adjust to thoughtful planning from home ahead of time, then much of the work can be done in a shorter shift. We use two seven-hour shifts each day. Many of our lab members prefer coming in the afternoon and working into the evenings, while others prefer the early-morning hours. They really will self-select. Overall, I think providing the lab a few different options and letting them choose the one that best fits their needs is important.”

The adjusted work hours have proven popular in her lab as well, McMahon said. “That’s going to be a process we continue even after we move to Phase Green,” she said. “Everyone is realizing how it enhances our efficiency to have that kind of schedule. They’re all seeing the benefits.”

7. Looking for more interaction online? Ban the mute button.

“A big change during the limited business model was having our lab meetings on Zoom,” McMahon said. “It was kind of awkward at first. My lab is very social — it’s a family feel. People like to be together, interacting, writing on the whiteboard to explain concepts. Students get a lot of practice thinking on their feet and drawing diagrams — that’s a big part of our lab meetings and that aspect was lost when we first went to Zoom. It took us a while to get back in our groove, using PowerPoint slides and other ways to communicate, including figuring out the whiteboard feature in Zoom. We haven’t mastered that yet, but at least we know it’s available.”

These lab meetings are large — “we typically have 15 or 16 people, since other students join my lab meetings,” McMahon said, “and they just didn’t have the same feel” on Zoom. “Normally people will interrupt and interject, but everyone other than the speaker had their audio muted,” McMahon said. “I finally had to say, ’Everybody, I want you to unmute. If someone’s dog starts barking, that’s fine. Feel free to interrupt and interject in the way we’ve always done. Now we’ve mastered that aspect, and people have gotten over that shyness.” In fact, “we are planning to continue those video lab meetings throughout the summer and into the fall,” McMahon said. “And it may be that we continue doing it this new way, even after we’re all back.”