Members of the Steyn lab in their BSL3 containment gear. Left to right: Ritesh Sevalkar, Ph.D., Hayden Pacl, Joel Glasgow, Ph.D., Sajid Nadeem, Ph.D., Vineel Reddy, Ph.D., and Krishna Chinta.

Members of the Steyn lab in their BSL3 containment gear. Left to right: Ritesh Sevalkar, Ph.D., Hayden Pacl, Joel Glasgow, Ph.D., Sajid Nadeem, Ph.D., Vineel Reddy, Ph.D., and Krishna Chinta.

While most of the world has done its best to stay as far as possible from SARS-CoV–2, the coronavirus that causes COVID–19, a select group of researchers moved closer. For some dedicated scientists at UAB, that means spending workdays and nights a few inches away from the planet’s Public Enemy No. 1.

To find a way to stop a killer like SARS-CoV–2 you must look it in the face — culturing the virus in a lab and keeping stocks on hand to test new treatments and perform crucial experiments.

Despite the fact that SARS-CoV–2 has spread across the globe, this is not the kind of work that can be done in a typical research space. SARS viruses require biosafety level 3 (BSL3) precautions, just one step below the maximum-security BSL4 conditions reserved for killers such as Ebola and Marburg virus. BSL3 “requires special airflow, laboratories and personal protective equipment,” said Joel Glasgow, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology.

UAB is one of a limited number of institutions with BSL3 labs — and a scientist, in Kevin Harrod, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, who has extensive experience developing vaccines and doing other close-up work with the original SARS coronavirus.

The work of the Steyn lab described here provides vivid examples of UAB’s Shared Values of collaboration, accountability, excellence and achievement in practice. |

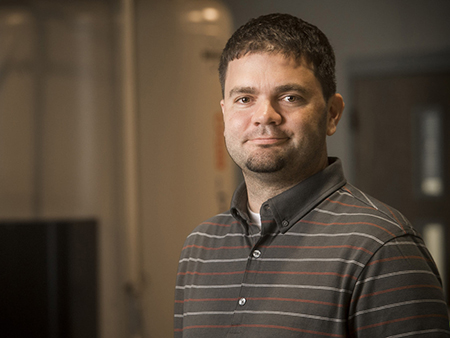

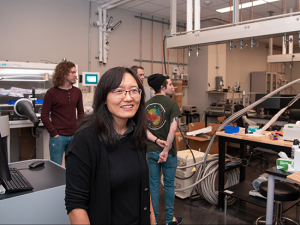

But this pandemic, Harrod’s third, found him in-between projects, without a fully staffed lab. That is, until a group of scientists from the lab of microbiology Professor Andries Steyn, Ph.D. — all BSL3 veterans from their work on the deadly bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis — volunteered to help.

When UAB entered its limited business model in March, all non-COVID research was put on hold. “While that was certainly not productive for our own research, it freed us up to use our BSL3 expertise to help with the COVID work,” Glasgow said. "Dr. Steyn encouraged us to jump in wherever we could.”

For the past several months, Steyn lab members have been assisting Harrod and staff scientist Jennifer Tipper, Ph.D., in initiating testing of treatments on SARS-CoV-2. Their work was entirely voluntary. “They could have been home working on grants and papers like everyone else,” Harrod said. "There has been a great deal of camaraderie and collaboration at the School of Medicine. Everyone is bringing their level of expertise to bear. That is one ancillary benefit of these tough times."

Motivation

So why did they come in?

“There’s a shared feeling amongst biomedical researchers that you want to be able to do something impactful and help patients,” said Hayden Pacl, a student in UAB’s Medical Scientist Training Program, in which participants earn their medicine and philosophy doctorates concurrently. “The sooner you can help in a pandemic setting it’s potentially exponential how many people you can save. We knew there would be a really large influx of people who wanted to do COVID research, but not a tremendous number of hands who are able to jump in and ready to go at BSL3.”

“We aren’t coronavirus experts, but we are very experienced in the methods and safety measures and all those aspects,” Glasgow said. “The methodologies required to work with both pathogens are similar.”

"The sooner you can help in a pandemic setting it’s potentially exponential how many people you can save." |

So are the stakes. Although it gets little attention in the United States, “the global TB burden dwarfs all other infectious diseases,” Glasgow noted. “A lot of estimates say that almost 2 billion people are infected with TB — about one out of every four people on Earth,” Glasgow said. In 2018, the disease killed 1.5 million people — mainly in Africa and India, where climate and other conditions allow latent TB to progress into deadly disease.

That is why Steyn, a native of South Africa, maintains another TB research lab at the Africa Research Health Institute in Durban, South Africa, where high rates of TB mean that there is a steady supply of infected lung tissue available from patients post-surgery. Steyn’s focus on translational research also has attracted a number of scientists from India to work in his UAB lab, Glasgow noted.

“India has a higher burden of TB — that’s one reason we are driven to work with this,” said postdoctoral fellow Ritesh Sevalkar, Ph.D. “Definitely if you can understand this pathogen it will help in contributing to society.”

“I wanted to do something translational,” said postdoctoral fellow Sajid Nadeem, Ph.D. Before he came to UAB, “I joined a lab that was designing a vaccine that could be a better alternative” to the BCG tuberculosis vaccine, Nadeem said. “That got me started in TB work and mechanistically in how it impacts cells.”

“I am very fascinated about the whole concept of how infectious diseases spread and result in epidemics and then pandemics,” said Krishna Chinta, a graduate student specializing in immunology in UAB’s Graduate Biomedical Sciences program. “Studying the immune responses to infectious diseases is my area of interest, which motivated me to volunteer to help move forward the COVID-19 research here at UAB.”

“This is my 15th year in TB research,” said researcher Vineel Reddy, Ph.D. “When I joined the lab, I didn’t know much about TB but from day one I was involved in generating various drug models.” In India, the focus “is all on the bug side,” Reddy added, so Dr. Steyn’s focus “on the host [human] side” was attractive, he said. The lab’s focus is in developing new treatments that enable the human host to defend itself against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This includes two high-profile papers, published in March 2020, identifying how the TB bacterium induces immune cells called macrophages to increase production of hydrogen sulfide and block the normal immune response. “Treatment for TB now takes four to six months,” Reddy said. “We are in the process of investigating several candidate drugs” that aim to shorten that timeframe.

“As an M.D./Ph.D. student, I started medical school five years ago, and the classmates I started with have since graduated and started residency,” Pacl added. “They have been treating patients over the last few months, and I began to feel a real frustration that I couldn’t help, too. This frustration was compounded by the fact that I want to study emerging infectious diseases throughout my career. So in the time that my classmates spent learning clinical skills, I’ve been learning how to safely conduct research on tuberculosis. I wanted this skillset so I would be able to help in just this instance, and I feel much more comfortable knowing I am doing the most I can do right now.”

What they’ve been working on

It takes a certain type of personality to spend your career in BSL3 environments. “You have to demonstrate proficiency in your work and your thoughts and plans,” Glasgow said. “Any time you do something, it requires creating a formal standard operating procedure, or SOP, that outlines methods you will use every time."

The Steyn lab is very familiar with writing and validating SOPs for their work with tuberculosis. Harrod’s group “had all the SOPs from their other virus work, but some of them hadn’t been validated for safety with regard to the coronavirus,” Pacl said. “That’s where we started, with the SOPs we would need to do the drug screening we’re working on now.” Then they moved into the BSL3 facility and “we each focused on a set of techniques,” Pacl said. “When those were ready, we moved to optimize the screen and assay itself.”

“I can’t say I was surprised that they stepped up to help.... Their voluntary participation provided a lifeline of help to both the safety and the research efforts." |

Careful preparation is key to minimizing time in the high-pressure, highly regulated BSL3 environment, Chinta noted. “The way we design the experiments, we try to do as much preparation as possible in the BSL2 lab,” he said. “In BSL3, a simple step of moving a plate from an incubator to a bacterial hood takes 10 minutes, because we have to change gloves every time we go in and out of the hood. So we try make the computations in the BSL2 lab and then go into BSL3 and start working.”

“We try to do as much as we can with regard to optimization or even substituting the pathogenic virus or bacterium for a surrogate strain in order to build evidence for justifying experiments in the BSL3,” Sevalkar explained. (The longest TB experiment he has participated in required 22 hours in containment with three breaks, Pacl said; the SARS-CoV-2 work, so far, has generally only lasted a few hours at a time in BSL3.) “Ritesh and I definitely had some late nights,” Pacl added. “Since we have validated the necessary SOPs and optimized our assay, we have ordered many more drugs, and Krishna and Sajid are also screening drugs with us.”

Meanwhile, Glasgow and Reddy have been helping to review the flood of paperwork from researchers with anti-SARS-CoV–2 ideas they want to test against the live virus. “Vineel and I have been reviewing SOPs on behalf of the office of Environmental Health and Safety and Dr. Justin Roth,” Glasgow said. There are several investigators who would like to get into UAB BSL3 labs, “and one of the things they have to do is provide their own SOPs that they will follow when doing the work,” he said. “Every BSL3 SOP has to be submitted, evaluated by experts and finally validated for safety before experiments can start.”

The Steyn lab has been operating in BSL3 containment for 17 years, Glasgow said. “We’re really connected to the Environmental Health and Safety personnel, and they and our lab have a great working relationship. There are maybe four or five labs at UAB who can evaluate those SOPs, and it was just an obvious way that we could help out.”

“I can’t say I was surprised that they stepped up to help — the Steyn lab members are a highly principled and remarkable group to work with,” said Roth, associate director for biosafety and the responsible official for Environmental Health and Safety. "They value safety as an integral component in support of their scientific achievements, so their voluntary participation provided a lifeline of help to both the safety and the research efforts. I am happy to see that their contributions are being recognized.”

For his part, Glasgow is quick to say that Roth “is doing an amazing job.” Much, if not all, “of the COVID research at UAB goes across his desk,” Glasgow said. “He’s been flooded by requests from UAB investigators wanting to gear up for COVID research, and I’m surprised he can find time to eat or sleep. He’s doing a stellar job. We’re really blessed to have him in that position.”

Although research activities have begun to move toward regular operations with the launch of Phase I of UAB’s reentry plan May 26, “to the best of my knowledge we are still going to be involved with Dr. Harrod as well as getting our TB projects going again,” Glasgow said.

Read more on COVID-19 research at UAB

UAB sleuths find drug candidate against COVID-19

Glow-in-the-dark coronavirus testing is first project of new hire

Researchers model COVID-19 infection in 3D human lung tissue

Tackling his third pandemic, UAB researcher gets up close with coronaviruses in order to kill them

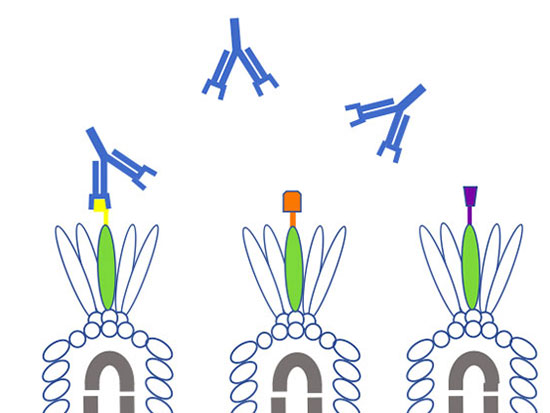

Researchers are creating a coronavirus showdown to settle pressing antibody problems

Where are the good antibodies against COVID-19? UAB project aims to find out

Helpful viruses may unlock the secrets of coronavirus antibodies

Cytokine storm treatment for coronavirus patients is focus of first-in-US study