Gary Hunter, Ph.D., had an idea for a research project two years ago, but he was hesitant to follow through with it.

Gary Hunter, Ph.D., had an idea for a research project two years ago, but he was hesitant to follow through with it.

Hunter, a professor of Human Studies, has had continual funding from the NIH for almost 20 years. Most of his work has focused on identifying metabolic factors that predispose individuals to weight gain. But his new idea took him in a new direction — one he wasn’t sure he wanted to pursue.

“I was 41 when I came here, and I’ve been at UAB for 28 years,” Hunter says. “I’m an exercise physiologist; I study exercise and obesity, and I’m not a young man anymore. I haven’t studied the brain, and that’s where my idea was going to take me. It was a new area, and I didn’t know how much I wanted to dig into it.”

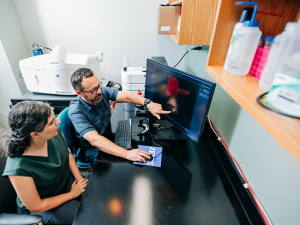

Hunter was inspired earlier this year, however, when the Nutrition & Obesity Research Center (NORC) announced a new contest called Creativity is a Decision. The unique competition was the brainchild of NORC Director David Allison, Ph.D., who wanted investigators on campus to submit their most creative ideas for grant proposals in obesity-related research. The contest was open to graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, faculty and staff.

Hunter was one of 35 applicants to submit one-page proposals, and his paper on the effects of problem-solving on brain glycogen was one of five selected as a winner for the inaugural award. Hunter and Julia Gohlke, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental health sciences, winners in the faculty and staff division, each received a $5,000 prize. Postdoctoral fellows Lekki Wood, Ph.D., and Gordon Fisher, Ph.D., each received a $2,500 award, and graduate student Tapan Mehta received $1,000.

Allison’s only stipulation for winners receiving the cash prize was that they had to submit their winning idea to an extramural sponsoring authority by end of November. Hunter, Gohlke, Wood and Fisher have submitted their proposals, and Mehta plans to submit his next year.

“One of the ideas behind creating this award was to shake people out of their shell — and not just young people,” Allison says. “We wanted to create a buzz with senior and junior investigators. What would you do in your last five years of working? Would you choose to do another study built upon what you’ve already done? Or would you say, ‘You know what, this is my last shot at a real big one. I’m going to go after something only if it’s really something exciting.’”

And the emphasis was on creativity. Those who wanted to enter were encouraged to not submit a proposal that was a minor extension of research they were already conducting.

“We didn’t want something safe or something most likely to get funded,” Allison says. “We told them to submit what they really think is the most creative. Everybody has those ideas that they think are neat and may be a little worried to say the idea to somebody because they are afraid they may get laughed at. This was about overcoming your fears.”

The role of brain glycogen

Hunter submitted his proposal to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases in October. Hunter hypothesizes that problem-solving leads to decreased brain glycogen, which leads to feelings of hunger, fatigue and tiredness. That chain of events leads to less physical activity and more eating, and the two together lead to weight gain.

Why might glycogen hold the key? Hunter says if feelings of fatigue occur in the brain, there has to be some signaling between the brain and muscle.

“There is clearly something that signals between the two, but we have no idea what it is,” Hunter says. “I got to thinking, well, what if it’s glycogen. What if, under normal circumstances, the glycogen in the brain tends to deplete proportionally at the same rate as muscles when you’re doing work. The more I read, the more it seemed to me that it could be one of the signaling factors for fatigue. It might also signal feelings of hunger.”

Hunter hypothesizes that some of our regular sedentary daily activities — working in front of a computer, reading books and watching television — may deplete brain glycogen, signaling to the body that it’s tired and hungry.

“Pretty much anyone you talk to, what do they say when they go home? They’re tired,” Hunter says. “And that’s whether they do a physical job or sit in front of a computer.”

Compounding the problem is that weight gain is associated with a reduction in insulin sensitivity, or the ability of insulin to remove glucose from the bloodstream. If we are insulin-resistant, our bodies have difficulty getting glucose into the brain. That chain reaction, Hunter says, might cause us to wake the next morning with slightly reduced brain glycogen.

“That means we will run out of glycogen more quickly and get tired and hungry faster,” he says. “It’s a spiraling effect.”

If Hunter’s project is funded by the NIDDK, he wants to give study participants a challenging brain task, measure their levels of tiredness, hunger and insulin sensitivity and measure energy expenditures. Then, he wants to see if 30 minutes of exercise will be sufficient to help the body push glucose and glycogen to the brain.

“We’re hypothesizing that 30 minutes of exercise will be good for getting glucose and glycogen in the brain and that it will improve insulin sensitivity as well. We think that even though people have burned a lot more calories because of the exercise, they won’t be as hungry or as tired.”

A new model?

Gohlke’s submitted proposal centers on using Daphnia, a small, fresh-water crustacean also known as the water flea, for high-throughput screening or as a much more cost efficient way of testing toxicity.

“It would be used as a screening tool and not replace mammal studies,” she says. “The Daphnia genome was recently published, and it’s a really unique organism. The study will evaluate the feasibility of using it as an inexpensive invertebrate model to explore thermal environment-energy storage relationships in a species with well-studied natural environments and easy laboratory manipulation. We believe that significant differences in lipid storage, metabolic rate, life history parameters and gene and protein expression will be evident in populations acclimated to high temperature regimes. We also hypothesize that acclimation to constant thermal regimes versus daily fluctuating thermal regimes will lead to increased lipid storage and reduced metabolic rate in Daphnia.”

Gohlke, who submitted her proposal to the National Institutes of Health through the new innovator awards program in October, says the opportunity to participate in the Creativity is a Decision contest is a tremendous help to her as an investigator.

“I’m just starting out in my career, and I’m constantly looking for feedback,” Gohlke says. “I thought this had significant potential. This was a clear indication to me that this was potentially a good idea.”

And Hunter agrees that seeking feedback is a key when it comes to research. That’s why the Creativity is a Decision awards struck a chord, he says. It gave researchers an opportunity to pitch a proposal — no matter how far-fetched or feasible it may seem — in a positive environment.

“Lots of people have innovative ideas, but usually we let them drop,” Hunter says. “The only thing I do know is that if you don’t try, you aren’t going to be successful. If you think you have a good, innovative idea, it’s good to bounce it off of people and see what they think about it. You never know what you might have.”