The diseases are familiar. So are the state’s rankings.

Alabama ranks 46th in obesity, 48th in diabetes, and 49th in high blood pressure, among other metrics. Turning these numbers more favorable is a grand challenge that Mona Fouad, M.D., director of the UAB Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center — and her team — have accepted.

Today, UAB has named Fouad’s Healthy Alabama 2030: Live HealthSmart project the winning proposal of the university’s first Grand Challenge, a key component of Forging the Future — UAB’s strategic plan. As the winner, Fouad’s team will receive a three-year, $2.7 million award from the university to fund the initial effort.

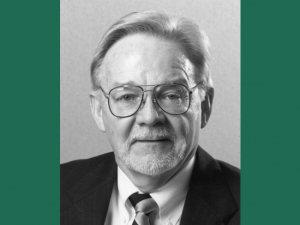

Mona Fouad, M.D.“Our health is everything,” said Fouad, a 2018 electee into the National Academy of Medicine. “It is the core of good quality of life, productive employees, successful students and happiness in general. We must do better by our citizens. We must educate, reach more people where they are and not put Band-Aids on problems, but work collectively to change our paradigm and improve our state’s health so we as Alabamians can reach our full potential.”

Mona Fouad, M.D.“Our health is everything,” said Fouad, a 2018 electee into the National Academy of Medicine. “It is the core of good quality of life, productive employees, successful students and happiness in general. We must do better by our citizens. We must educate, reach more people where they are and not put Band-Aids on problems, but work collectively to change our paradigm and improve our state’s health so we as Alabamians can reach our full potential.”

Fouad’s comprehensive approach to fixing these complex problems includes 90 partners on her Grand Challenge team from government, business, education and more in both leadership and advisory roles.

“It is very fitting — and by design — that we embark on our Grand Challenge in UAB’s 50th anniversary year, and it is equally fitting that a nationally recognized pioneer in health disparities research like Dr. Mona Fouad will work with a large team of collaborators to solve our state’s most complex health problems,” said Ray Watts, M.D., president of UAB. “She has assembled an impressive coalition of collaborators and supporters from our university and across the state. UAB’s phenomenal growth and success over five decades have been fueled by intense collaboration and innovation, and those very strengths — in their fullest measure — will enable us to achieve our Grand Challenge.”

Grand Challenges are ambitious goals that have the potential to capture the public’s imagination. They are designed to increase support for policies and investments that foster innovation. They also serve as compelling “North Stars” for cross-sector and multidisciplinary collaboration.

“Like America’s goal to put a man on the moon, Grand Challenges have a history of catalyzing innovation for the benefit of society,” said Christopher Brown, Ph.D., vice president for Research at UAB. “When we announced this endeavor, we said it would unite university activities — teaching, research, scholarship, commercialization, patient care and service — along with the capabilities of partnering organizations to solve large-scale problems affecting Alabama. Our rankings indicate the health of our state is a large-scale problem. The team Dr. Fouad has assembled will find the solutions needed to positively impact those numbers, which will help our citizens achieve better health and propel our state forward.”

Fouad’s ambitious project aims to elevate the state of Alabama out of the bottom 10 in national health rankings by 2030. Her plan will utilize a systematic and comprehensive approach to make significant improvements in key health metrics over the next 10 years.

Stepping up from the cellar

The long-term goal is to get Alabama’s health rankings into the 30s in key metrics — obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol — “which will take about 10 years,” Fouad said. For example, reducing the state’s obesity rate from 36.3 percent to 33 percent would move Alabama from 46th to 37th nationally.

The mid-term objective to achieve that will be “to improve health behavior — getting people to eat more fruits and vegetables, exercise, stop smoking, lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and screen for cancer and chronic diseases,” Fouad explained.

The strategies behind it all, she says, fall into three categories: changing the rules through policy initiatives, changing structures such as schools and workplaces through new programs, and changing places through environmental improvements, such as adding sidewalks or street lighting.

These three often go hand in hand. Updates to land-use zoning codes, innovative educational programs to encourage exercise and physical improvements such as new sidewalks can combine to make neighborhoods more pedestrian-friendly and increase physical activity rates, for instance.

“We need a comprehensive approach to fix this complex problem, which is why our Grand Challenge team includes 90 partners from government, business, education and more in both leadership and advisory roles,” Fouad said.

Theresa Wallace, Ph.D., William Anderson, Ph.D., Paula Alvarez Pino, Mona Fouad, M.D., MPH, Lisa McCormick, Dr.PH, Anna Threadcraft, RDNCollaboration and partnerships will be key, Fouad adds.

Theresa Wallace, Ph.D., William Anderson, Ph.D., Paula Alvarez Pino, Mona Fouad, M.D., MPH, Lisa McCormick, Dr.PH, Anna Threadcraft, RDNCollaboration and partnerships will be key, Fouad adds.

“We were very pleased with the planning phase built into the UAB Grand Challenge process,” Fouad said. “That gave us time to engage with the community. We held a series of partner and town hall meetings where we met with citizens, organizations and more than 100 community leaders in five counties. We developed our strategies based on the needs and challenges they shared with us.”

Theresa Wallace, Ph.D., a program director in the Division of Preventive Medicine, is the program director for the Healthy Alabama 2030 project. She says three common themes emerged from the town hall meetings.

“People talked about modifying the built environment so physical activity is easier or more accessible, changing the food environment to promote good nutrition, and transforming the health care setting to facilitate prevention and wellness,” Wallace said. “People want to know, ‘How can I transform my community into one where healthy living is the easy, default choice? How can I proactively take my health into my own hands?’ If we do it effectively, which we’ve done in the past, we can truly make a difference.”

Prescriptions for change

Healthy Alabama 2030 will launch with demonstration zones at UAB and in three Birmingham communities, Fouad says. These communities — Woodlawn/Kingston, Bush Hills/Ensley, and Eastlake — are central to the city’s strategic plan, she adds. Healthy Alabama 2030 complements strategic plans and initiatives at UAB and other partner organizations, including the state Department of Public Health.

To make major change, the team will leverage programs that already have proved successful on a smaller scale, Fouad says. For example, UAB Wellness initiatives have led to a 13 percent increase in screening rates for colorectal cancer and given thousands of employees eye-opening insights into their health through the WELLSCREENS campaign. “This project collectively pulls together so many good things that are already happening,” said Employee Wellness Director Anna Threadcraft, who is co-principal investigator for systems in the Healthy Alabama 2030 team. “We can share what works and what doesn’t so we all get better.”

A program from the MHRC’s Birmingham REACH for Better Health initiative, Parks Rx, has been connecting residents to 139 Birmingham-area parks since 2016. Physicians with the Jefferson County Department of Health write “exercise prescriptions” for their patients. When patients enter their ZIP codes on a smartphone, computer or health department kiosk, they get directions to the closest parks, along with details such as trail length, hours and pet policies. Another REACH partner distributes produce to small corner convenience stores in Fountain Heights. “What if we have an app that connects to the trucks and to food banks so that residents can see when the trucks are coming and what they have in stock?” Fouad said. “Everyone has a smartphone now. We are trying to develop innovations that are sustainable.”

Students will also play a major role in making a difference through new service-learning opportunities, says Lisa McCormick, DrPH, associate dean for Public Health Practice in the School of Public Health and co-principal investigator for Measures and Evaluations for Healthy Alabama 2030. That could include everything from mapping abandoned structures to mentoring in local schools. “We teach students these skills in the classroom — this is the application,” McCormick said. “This will show students how they can work in Alabama communities to solve Alabama problems.”

Solving problems close to home is a great motivator for faculty as well, Fouad says. “Everyone is excited,” she said. “We know we can improve, and we know the behaviors to focus on. The Grand Challenge has given us a great opportunity to scale up the successful projects we’ve piloted and sustain them for the long term. We’re all joining together to have a lasting impact on our campus, the city and the entire state.”