The source of the deadly enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (E. coli) outbreak in Europe that has infected more than 2,100 and killed at least 22 is still a mystery.

|

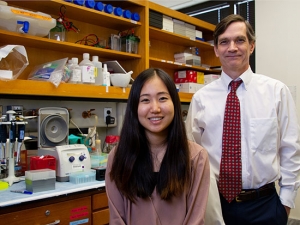

| David Freedman, director of the UAB Traveler’s Health Clinic and co-director of GeoSentinel, says it’s unclear how long the E. coli outbreak in Germany will persist. |

David Freedman, M.D., director of the UAB Traveler’s Health Clinic and a preeminent travel-medicine physician and researcher, has been in close contact with his contemporaries in Germany since the outbreak began there in early May. Sprouts, lettuce and cucumbers have been linked by epidemiologists as the potential culprits, but all bacterial cultures have come back negative and German authorities still are searching for answers.

“They have not pinpointed the cause yet,” Freedman says. “The disease seems to be and typically is a food-borne disease. Since all cases have been acquired in northern Germany, it is likely a domestic cause and not due to imported food.”

Freedman was appointed to the World Health Organization International Health Regulations Roster of Experts in 2010. A professor in the UAB departments of Medicine and Epidemiology, Freedman also co-directs GeoSentinel, a global online network of 54 travel- and tropical-medicine clinics spread across all continents. The network is a partnership of UAB, the International Society of Travel Medicine, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other groups and it has enabled Freedman to stay current on the events.

The number of suspected U.S. cases involving the deadly E. coli bacteria at the heart of this outbreak is currently at four. U. S. officials have said all four U.S. patients recently visited Hamburg, Germany.

Freedman says concerns this strain of bacteria will spread in America are minimal. Passing the bacteria from person to person is difficult.

“This is a disease that can be contagious from person to person if you get contaminated by somebody’s stool or there’s not good sanitation or hygiene,” Freedman says. “There does not seem to be any local transmission by people who have gotten the disease and left Germany.”

How do you prevent person-to-person transmission? Freedman says it’s as simple as practicing good cleanliness.

“It’s really a matter of hygiene and hand-washing,” he says. “We’re used to that in the United States because of swine flu and other respiratory illnesses we’ve experienced in recent years. As long as someone who has diarrhea maintains good hygiene and anybody who has exposure to them washes their hands afterward, there shouldn’t be any risk of person-to-person transmission.”

Freedman says the likely cause is a raw vegetable found in salad, which is why cucumbers, bean sprouts and other sprouts have been tested.

German officials have suggested their residents take precautions. Residents in northern Germany were told specifically to stop eating raw salads.

“In fact, the restaurants in Hamburg are only serving boiled vegetables now,” Freedman says. “You can’t get a raw salad right now. That’s probably why the number of cases being reported are slowing down.”

The Food and Drug Administration says there are no indications the U.S. food supply has been tainted by E. coli. However, as a safety precaution, the FDA said it was monitoring fresh tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce and raw salads imported from areas of concern. The officials also say countries in Europe are not a significant source of fresh produce for the United States.

Freedman says it’s unclear how long the outbreak will persist. He says there have been no indications that this bacteria is more nasty or virulent than the typical enterohemorrhagic E. coli. He believes this outbreak may be more widespread in Germany because more food than normal was contaminated.

“Oftentimes one small batch of food somehow gets contaminated either in the fields or in production or transportation,” Freedman says. “What must have happened here is that a much larger amount of food somehow got contaminated between the farm and distribution in northern Germany.”

Freedman says that generally enterohemorrhagic E. coli affects children ages 5 and younger, males and females equally. But in this outbreak, most of the people affected are adults age 20 and older. And in fact, the peak incidents are in people in their 30s. There also have been few cases reported in elderly people, another oddity.

“The other unusual thing — and so far there is no explanation or theories for this — women are affected twice as often as men,” Freedman says. “Some 67 percent of the cases have occurred in females. We have no idea why that is true. This is a unique strain though; it doesn’t appear to be more virulent, but it is a strain that has not been described as causing significant human disease before.”

As far as traveling goes, Freedman says there shouldn’t be any major worries.

“Travelers don’t need to really be concerned,” he says. “It seems to be northern Germany that is most affected by this outbreak. There shouldn’t be any widespread panic. People shouldn’t delay or change their plans to travel in Europe or even northern Germany. All they have to do is be careful about what they eat.”