Anybody who has ever attempted to lose weight can attest to the difficulty. Changing eating habits, learning to exercise and gaining self-control isn’t easy. But once you’ve reached your goals, the next hurdle is often a little bit higher — keeping the weight off.

|

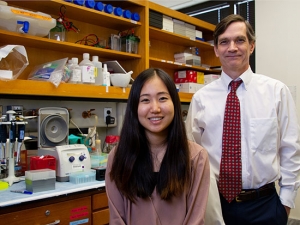

| In a new preventive medicine study, Gareth Dutton hopes to determine what types of long-term programs help people manage weight-loss over time. |

Gareth Dutton, Ph.D., associate professor of preventive medicine, is seeking participants for the Improving Weight Loss (ImWeL) study, which aims to learn what types of long-term programs help people manage weight-loss over time. Dutton hypothesizes that brief but intensive periods of follow-up care may serve to bolster patients’ motivation and more effectively address any relapse problems.

“As difficult as it is to lose weight, weight-loss maintenance is inherently more challenging, and research shows that most individuals regain much of their lost weight after treatment ends,” Dutton says. “Extending treatment to include some type of follow-up, or booster sessions, is one of the best ways to minimize a regain of weight. However, we do not really know the best formula or schedule for these maintenance visits. The most common procedure is to see patients on some type of fixed-interval schedule, such as monthly visits. However, this may not be the most effective method for patients who face a number of environmental, motivational and biological challenges when trying to maintain a new, healthier weight.”

The trial will examine the effects of an alternative schedule of follow-up, which Dutton refers to as a clustered campaign approach. This alternative approach will include sets of clustered treatment sessions that share common themes or campaigns.

Participants will have more frequent contacts with treatment staff during these brief periods of time, which Dutton believes may offer novelty and keep participants engaged in long-term treatment as well.

To evaluate this alternative approach, overweight and obese adults will be enrolled to participate in a 16-week behavioral weight-loss program. Those who achieve a pre-specified amount of weight loss (5 percent of initial body weight) will be eligible and randomized into a 12-month extended-care weight-loss maintenance program. The purpose of the randomized trial is to compare the weight-loss maintenance outcomes of two extended-care obesity programs — the clustered campaign approach and a self-directed comparison condition.

The study, which is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), will take place in Medical Towers, and there is no cost for participation. Study participants will receive a $25 gift card for each complete assessment. All information given as part of the trial is confidential. For more information on the ImWeL study or to take part, call 975-7108 or email IMWEL@dopm.uab.edu.

Dutton says there are several factors that combine to make keeping lost weight off difficult.

The abundance of new technology has contributed to creating a more sedentary lifestyle for many, and of course there are lots of high-calorie, high-fat foods readily available to us any time of the day or night. There are biological factors at play, too. Our bodies may respond to weight-loss by reducing its rate of energy expenditure, and subsequent hormonal changes may increase our appetite.

But motivation also plays a big role. Sure, we’re motivated to get the weight off, but keeping it off?

“The thing is, maintaining the same weight — even if it’s a new, healthier weight — is less fun and reinforcing than losing weight,” Dutton says. “When you’re initially losing the weight, that’s rewarding and people are noticing and complimenting you. You’re feeling better and your clothes are fitting better. It’s not as much fun to wake up tomorrow and weigh the same as you weighed yesterday. It’s not as reinforcing. And that can be a battle.”

There is good news, however. Many people are very successful in long-term maintenance. Dutton says the research at UAB and elsewhere has developed a better picture of those characteristics and behaviors that seem to be associated with long-term success, including maintaining a relatively low-calorie and reduced-fat diet and engaging in physical activity for at least one hour a day.

Another area closely tied to long-term success is continuing to self-monitor after you have achieved weight loss.

“Watching and recording what you’re eating and how much you’re eating and weighing yourself regularly — even daily — can be helpful,” Dutton says. “All of those self-monitoring behaviors are crucial because it gives you that immediate feedback to let you know if you’re getting off track — even before you see it much on the scales.”

Dutton, who came to UAB from Florida State in summer 2011, has taken part in other lifestyle interventions and weight-loss trials focused on diet and exercise, specifically in implementing these types of programs into applied clinical settings.

“I’m interested in doing that here as well,” Dutton says. “It’s great to be able to take these programs that we know can work in well-controlled circumstances and translating and implementing them in real-world settings — like the primary care office, managed care or in school settings or other places in the community where they can have a broader reach or impact.”