A low-cost, essential newborn care (ENC) education-training program rooted in basic neonatal care and resuscitation and adapted by UAB researchers has the potential for saving more than 1 million lives worldwide each year, according to study data and commentary published in the November issue of Pediatrics.

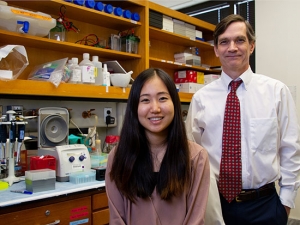

The commentary was published simultaneously with research findings led by Wally A. Carlo, M.D., director of the Division of Neonatology, and senior author Linda L. Wright, M.D., scientific director of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics developed the education-training program for implementation in developing countries. When it was put into action, the program reduced early neonatal mortality by almost 50 percent.

The commentary was published simultaneously with research findings led by Wally A. Carlo, M.D., director of the Division of Neonatology, and senior author Linda L. Wright, M.D., scientific director of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics developed the education-training program for implementation in developing countries. When it was put into action, the program reduced early neonatal mortality by almost 50 percent.

The study was designed to train midwives in basic neonatal care and resuscitation techniques at 18 urban low-risk community health clinics in Lusaka and Ndola, Zambia.

“Together with our multi-country trial published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine, our research shows that this educational intervention can markedly reduce perinatal mortality — babies who die just before being born and babies who die in their first week after birth,” Carlo says. “We have taught caregivers to identify babies who appear dead, but can be resuscitated. We’ve taught them how to check the heart rate and how to determine that the baby can breathe if brought to life simply by using cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). CPR is 99 percent effective in neonates if done appropriately. This has the potential to be a game changer for people in underdeveloped countries around the world.”

Funding for the project began 10 years ago with a UAB grant to develop a resuscitation program in Zambia. Carlo secured an NIH grant and three subsequent grants for this work along with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Birth asphyxia, low birth-weight/prematurity and infections are major causes of death during the first month. The low-cost interventions in this study are effective in preventing stillbirth and perinatal deaths in community births, including home births.

Using the train-the-trainer model, local instructors trained birth attendants from the two largest cities in Zambia. They used the World Health Organization (WHO) essential newborn-care course and a modified version of the American Academy of Pediatrics Neonatal Resuscitation Program.

“The midwives were trained to do several easy steps that are critical for babies to survive at birth and be kept alive through the first week of life,” says Carlo, who also delivers this type of training to doctors and nurses throughout Alabama. “We selected these courses because our preliminary research has shown they contain the essential interventions necessary to sustain life in many infants and are a cost-effective educational package that can be used anywhere in the world. The midwives taught the mothers to provide care to the baby at home during the first week after birth.”

A total of 71,689 neonates were enrolled in the three study periods. Seven-day mortality decreased from 11.5 deaths per 1,000 births to 6.8 deaths per 1,000 births after the midwives received training.

Babies who die just before being born in developing countries — or fresh stillborn babies — usually have no signs of being alive. But Carlo says while the baby may not be breathing, in most cases it has a slow heartbeat. In fact, Carlo says, 10 percent of all babies born worldwide don’t breathe at birth, and UAB Hospital has in-house neonatologists 24 hours a day specifically to help babies who need resuscitation, including those who appear to be fresh stillborn.

Stimulation helps close to 5 percent of those babies. The other 5 percent require air pushed into the lungs with bag and mask ventilation.

“That’s what we’re doing in Zambia and many other countries,” Carlo says. “We’re helping them breathe simply by giving them a few breaths.”

The success of helping these babies breathe in Zambia has been staggering. When Carlo first went to Zambia in 2002, the fresh stillbirth death rate was 100 per 1,000 in the first minutes of life. That number has been cut to 4.9 per 1,000 in eight short years.

“It’s hard for us to understand how far behind developing countries have been,” Carlo says. “We didn’t establish a CPR program for babies in the United States until 1987. We don’t see and experience what people in underdeveloped countries experience every day. We’re just trying to help them catch up. Right now, their rate of infant mortality is about what it was here in the United States in the beginning of the 20th century. And we’ve come a long way since then.”

Next steps

The American Academy of Pediatrics, NIH and WHO developed the Helping Babies Breathe program, adopting the model developed by Carlo to spread the training to countries worldwide. And companies like Laerdel, supplier of basic and advanced life-support training products and emergency medical equipment, are donating equipment to help the cause, Carlo says.

“The big next step is to expand this worldwide, and many organizations, including Save the Children and the United States Agency for International Development, are helping to do that,” Carlo says. “The leaders at Laerdel think this is a fantastic idea, and they are supplying most of the 10 sites where the program is being scaled up.”

Another recent study from Carlo’s team in the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research supported the findings of the train-the-trainer model for reducing stillbirth. They found that a basic three-day ENC training program reduced the rate of stillbirths in six resource-poor countries by more than 30 percent.