Life in Check enables users to manage daily tasks in a functional, simple-to-use format.Two College of Arts and Sciences professors teamed up to teach a course to help students build empathy and increase their mobile app design skills.

Life in Check enables users to manage daily tasks in a functional, simple-to-use format.Two College of Arts and Sciences professors teamed up to teach a course to help students build empathy and increase their mobile app design skills.

Sally Cramer, Ed.D., visiting assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History, and Stacy Moak, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, created the spring iteration of ARS 495 Tapworthy Mobile App Design, a course that challenged graphic design students to conceive, design and prototype apps that alleviate community reentry barriers for people who have been incarcerated.

Understanding the issues

Each year, more than 600,000 individuals are released from state and federal prisons, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and another 9 million cycle through local jails. More than 66% are arrested within three years of their release date, and half are reincarcerated.

|

I really am hopeful they’ve come out of [the class] even more empathetic, so one day if they’re in a position to hire people, if a resume of a previously incarcerated person comes across their desk, they can let them give their story and give them a chance. It was totally more than just a class.” |

When planning ARS 495, Cramer wanted her students to create an app with a purpose. A friend and fellow instructor in criminal justice suggested a mobile app to help incarcerated Americans reenter public life by providing easy access to resources to help them succeed.

In October 2020, Moak, who also holds secondary appointments in Social Work and Criminal Justice, co-hosted a webinar to address these issues with members of Birmingham’s Offender Alumni Association, a network of former offenders who inspire each other to reduce recidivism, develop healthy relationships and provide social, economic and civic opportunities. Cramer saw the panel advertised in a September 2020 eReporter, and reached out to Moak. The two collaborated to design a course to help students better understand the life experiences of former offenders and design apps tailored to those specific experiences.

“Stacy helped our class by providing us information and educating us,” Cramer explained. “None of us knew anything about the Alabama criminal justice system, and we learned so much.”

Stacy Moak, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, and Sally Cramer, Ed.D., visiting assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History“It was a kind of service-learning component inside a tech class,” Moak added. “Students learned they have the ability to help people through their knowledge base. They felt they were really designing something that could be useful and helpful — they felt connected. That’s a different level of learning that’s outside classroom knowledge and steps into community engagement.”

Stacy Moak, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, and Sally Cramer, Ed.D., visiting assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History“It was a kind of service-learning component inside a tech class,” Moak added. “Students learned they have the ability to help people through their knowledge base. They felt they were really designing something that could be useful and helpful — they felt connected. That’s a different level of learning that’s outside classroom knowledge and steps into community engagement.”

Application creation

Students participated in educational sessions with policymakers and community organizations such as the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Offender Alumni Association, Southern Poverty Law Center, a journalist and several previously incarcerated people.

“Hearing from policymakers set context for where we are in the Alabama prison system and our legal system,” Moak explained. “The second panel was made up of formerly incarcerated individuals, some recently released, some who had been out a long time. Students were very intentional about listening and learning in order to create an app that didn’t aggravate any sensitivities.”

Throughout the design and prototyping process, students had to consider a variety of technical aspects, Cramer explains. She used Josh Clark’s textbook, “Tapworthy: Designing Great iPhone Apps,” throughout the course.

“When designing an app, you have to think about things like where your thumb rests and how far you are able to move it, and then what you intentionally place, or not place, within that area of your design,” she said. “During planning, we answered questions about our mission, our target audience, what names would look best under an app icon, color schemes, any potential sound issues. Students developed a list of must-have items. We’re creating app version 0.01 — what should be in it to get the basic working model? Then I asked them what are your dreams? What are your long-term goals?”

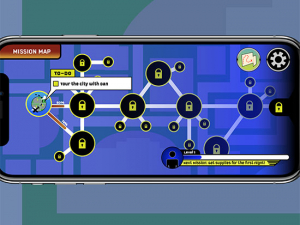

LifeTrack is a simulation game for navigating a post-incarceration world.Based on what they learned in class and from the panels, students created two apps — Life in Check and LifeTrack.

LifeTrack is a simulation game for navigating a post-incarceration world.Based on what they learned in class and from the panels, students created two apps — Life in Check and LifeTrack.

Life in Check enables users to manage daily tasks in a functional, simple-to-use format. A chat feature helps users connect with others in their community and a resource hub helps access information such as birth certificates and drivers’ licenses and includes links to mental health and financial services.

LifeTrack is a simulation game for navigating a post-incarceration world; it uses a series of real-world resources, scenarios and character guides to provide an engaging, informal user experience. Users navigate a series of quests such as building a support system by befriending civilians, exploring the in-game city to find helpful resources and complete missions that help them learn to build and apply real-world skills, all with the goal of fostering a well-rounded life and career.

The students were not expected to code working apps, Cramer explained; rather, they designed prototypes in Adobe XD, a vector-based, user-experience design tool for apps students can access for free through UAB’s partnership with Adobe. After prototyping in XD, students created a movie version of app use with Adobe After Effects.

|

“Students learned they have the ability to help people through their knowledge base. They felt they were really designing something that could be useful and helpful — they felt connected. That’s a different level of learning that’s outside classroom knowledge and steps into community engagement.” |

The way forward

Cramer and Moak, who presented virtually on ARS 495 to the Justice Arts Coalition’s Art for a New Future conference in June, are investigating grant funding to develop and deploy Life in Check and LifeTrack for use. But the course outcomes extend beyond technology, Cramer says.

“The strongest feedback I got from students is how they wished they’d had longer to work on this particular project,” she said. “They got so much out of it. I really am hopeful they’ve come out of [the class] even more empathetic, so one day if they’re in a position to hire people, if a resume of a previously incarcerated person comes across their desk, they can let them give their story and give them a chance. It was totally more than just a class.”