|

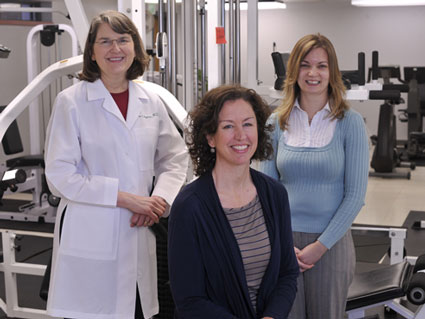

| (From left) Laura Rogers, M.D., Sara Mansfield and Amanda Fogleman |

Fifteen years ago, there was so little known about cancer that the main goal of many oncologists was to get their patients through grueling treatments.

That’s not the case any longer. Many treatments have become targeted and highly specialized, and patients are living longer — including breast cancer patients. Because of this, there is a major focus on improving the quality of life after treatment.

A unique breast cancer exercise study headed up by Laura Rogers, M.D., professor of nutrition sciences, aims to pinpoint what factors can lead survivors to begin and sustain an exercise program that will ultimately lead to positive lifestyle change.

“We’re trying to give breast cancer survivors the tools they need to start an exercise program, and we want to determine what pathways lead them to continue exercising long after their treatment has ended,” Rogers says. “We want to know what kind of support they need.

“Do they need one-on-one engagement? Do they need the atmosphere that a support group would best provide? Is it best to be on your own but report what you do to someone? Do they need accountability at home? Those are all of the different aspects of the intervention that we’re investigating in an effort to determine the best combination,” she says.

The Better Exercise Adherence after Treatment for Cancer (BEAT Cancer) study is funded by a $3.5 million federal grant from the National Cancer Institute and is currently enrolling women who have had a breast cancer diagnosis, are finished with treatment and are not engaged in a regular exercise program.

Half of the women who enroll will be randomly assigned to receive the BEAT Cancer program. The 12-week program encourages women to walk at a healthy pace, beginning with 20 minutes a day three times a week and working toward the recommended time of 150 minutes a week. Those interested in participating can call 205-975-1247 or email moveforward@uab.edu for more information.

| The BEAT Cancer program: A 12-week program that encourages women to walk at a healthy pace, beginning with 20 minutes a day three times a week and working toward the recommended time of 150 minutes a week. Those interested in participating can call 205-975-1247 or email moveforward@uab.edu for more information. |

During the program’s first six weeks, enrollees will receive coaching from an exercise specialist and learn how to use a heart rate monitor. In the last weeks of the program, volunteers will be responsible for maintaining their own exercise regimen at home, but an exercise specialist will be available for support.

Study participants will have follow-up visits at three, six and 12 months for physical assessments. Participants will be compensated $50 for their initial assessment and after completing each of their three other evaluations. The women who are not assigned to receive the program will receive three free exercise sessions with a cancer exercise trainer at the end of the study.

Rogers hopes the study will lead to the creation of educational training materials that can be taken to cancer centers around the country to train staff on how to incorporate these interventions with their patients.

Finding what works

The BEAT Cancer study originated with Rogers when she was on faculty at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, and has enrolled 175 participants so far in Springfield and Champaign, Ill. Rogers brought the program with her when she came to UAB this past fall.

Joining her in administering the grant are Sara Mansfield, a cancer exercise specialist, and Amanda Fogleman, project administrator.

Rogers has been working for the past eight years to design a way to help breast cancer survivors exercise more regularly and prove exercise benefits for patients after breast cancer diagnosis.

Her previous studies have found that breast cancer survivors counseled to engage in exercise significantly improved their physical activity and health outcomes after the intervention. After one intervention, 60 percent of previously sedentary breast cancer survivors were still exercising 150 minutes a week.

“We started having focus groups with breast cancer survivors about six to eight years ago — talking to them in the clinic, sending out mail surveys trying to get an idea about exercise and what they would like in an exercise program,” Rogers says. “As you would expect, there was lots of individual variation. Some people love to exercise in a group, some don’t. But there were some consistent findings, and one is that many feel injured by the cancer experience, and they are afraid they will injure themselves further.”

“Most of the people coming to us know they should be exercising,” Mansfield adds, “but they just can’t get themselves to do it.”

In addition to fear, another common theme survivors mention is time, or lack of it. Many survivors focus on re-engaging in their lives after treatment, and often that means taking care of others in their family or in their job.

“They often say they are so busy trying to do things for everybody else that they don’t have time for themselves,” Mansfield says. “They’re last on the priority list.”

Critical time

But this time after treatment is crucial for survivors. Once they are cancer-free and the regular doctor visits stop, they must return to their usual activities and adjust to their new normal. A cancer diagnosis is often a motivator to adopt a healthier lifestyle, and women may struggle to determine how best to do this. And during this time, it’s not uncommon for the effects of the treatment to continue to cause some issues, especially in terms of fatigue.

“That’s one of the things we want to find out — if our exercise program can help reduce some of the effects of the treatment, including fatigue, and if can it improve body composition,” Mansfield says.

There also is a psychological component to consider. Rogers says an exercise program can bring benefits to survivors. It’s something they can do for themselves and it gives them a sense of control, especially after months or years of enduring surgeries and treatments.

Study enrollees assigned to participate in the BEAT Cancer program will address these and other issues during six discussion group sessions in the 12-week study. Participants will meet with other breast cancer survivors participating in the study at the same time and will discuss ways to manage time and stress and how to prepare for times when things arise that interfere with exercise.

“These groups really talk about how to think differently about exercise, how to think more positively and deal with the barriers they inevitably will face,” Rogers says. “We want them to identify how to overcome barriers, pull together their social support and build their confidence, which includes feeling less afraid. We’re going to look at which issues the intervention targets that work best for helping these women continue their exercise after finishing the program. These group sessions will help them develop a plan so survivors can improve their physical functioning and quality of life by exercising now and in the future.”

Help the Graduate School and Staff Council provide much-needed items to the Ronald McDonald House and Birmingham-area schools.

Help the Graduate School and Staff Council provide much-needed items to the Ronald McDonald House and Birmingham-area schools.