Is smoking-cessation success tied to sleep quality? A new UAB study is examining this question.Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States and worldwide. Yet despite similar rates of smoking, Blacks experience disproportionately greater harms from smoking than whites. For instance, Blacks are more likely to die from smoking-related diseases than whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Is smoking-cessation success tied to sleep quality? A new UAB study is examining this question.Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States and worldwide. Yet despite similar rates of smoking, Blacks experience disproportionately greater harms from smoking than whites. For instance, Blacks are more likely to die from smoking-related diseases than whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC survey data shows that 72.8% of Black adults who smoke cigarettes daily reported that they wanted to quit, compared to 67.5% of whites and 67.4% of Hispanics — and 63.4% of those Black smokers had attempted to quit, compared with 53.3% of whites and 56.2% of Hispanics. But Blacks are less successful when attempting to quit compared to white and Hispanic cigarette smokers, the CDC data show.

“There have been lots of studies on this, which have suggested that maybe the disparity is because African Americans smoke more menthol cigarettes [which may be more addictive than non-menthol cigarettes and may allow toxic chemicals in smoke to be more easily absorbed into the body], have lower incomes or less access to treatment,” said Karen Cropsey, PsyD, professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, and co-director of the Center for Addiction and Pain Prevention and Intervention (CAPPI) in the School of Medicine.

A little-studied connection

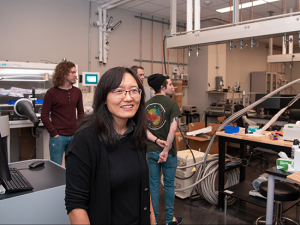

Cropsey, who specializes in smoking-cessation research, and Karen Gamble, Ph.D., an associate professor in the psychiatry department, are co-principal investigators for a new five-year, nearly $3 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to examine a little-studied connection: between smoking-cessation and sleep quality.

|

Blacks are more likely than whites to have problems with sleep, including shorter sleep duration and shifted circadian timing. Poor sleep quality is predictive of a person’s relapse from smoking-cessation programs, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults. |

Gamble studies circadian clocks, the specialized genes operating throughout the body to synchronize people with their environments. These clocks are largely responsible for an individual’s chronotype, or “your best-feeling time of day,” Gamble said. This can lie anywhere on a continuum from extreme rise-with-the-dawn early birds to the latest of night owls. A person’s chronotype, and whether they are working with or against that chronotype, can play a major role in health and disease, as Gamble and other circadian researchers have shown repeatedly. People who work on the night shift, for instance, have increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer — and poor sleep is one big reason why.

Blacks are more likely than whites to have problems with sleep, including shorter sleep duration and shifted circadian timing, Cropsey said. Poor sleep quality is predictive of a person’s relapse from smoking-cessation programs, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults, she added. But few studies have combined these two observations to specifically examine temporal patterns of smoking. And no studies have looked at the relationship between sleep duration or timing and smoking in minorities.

“We were wondering if these intrinsic differences in circadian properties predict how successful you would be if you tried to quit smoking,” Gamble said. “If we can figure this out it could lead to more tailored therapies for smoking cessation.”

Disparities in 'peak craving time'

Cropsey and Gamble are collaborating with Michael Businelle, Ph.D., director of the Oklahoma Tobacco Research Center at the University of Oklahoma. Businelle has developed a platform that enables researchers to design customized mobile health applications for collecting real-time data on study participants’ behaviors. These apps enable participants to tap a button every time they smoke a cigarette, for instance, or to rate their level of craving at various times throughout the day. In preliminary work, Gamble analyzed data from Businelle’s lab on smokers’ craving levels over 24 hours. “We found these racial disparities” in the peak craving time, Gamble said.

|

“We were wondering if these intrinsic differences in circadian properties predict how successful you would be if you tried to quit smoking. If we can figure this out it could lead to more tailored therapies for smoking cessation.” |

“Time to first cigarette” is a measure commonly used by researchers to estimate the strength of a smoker’s addiction. The sooner a person lights up after waking, the greater their cravings level tend to be and the harder it is for them to quit. “When you look at whites, the urge to smoke tends to be highest early in the morning” overall, Cropsey said. “Time to first cigarette works well for white people, but in Blacks it seems to be a very different urge.”

Three-part study

How different? The study aims to find out through a three-part process. In the first, the researchers will survey 600 participants — one-third of them smokers, the rest non-smokers — on their sleep patterns and tobacco use. “We want to know, Can we predict who is more likely to be a smoker or non-smoker based on sleep and circadian rhythms, and how does that break down across racial groups?” Gamble said. Then they will give a smaller group of smokers an actigraph watch — a research-grade activity band, similar to but more precise than a Fitbit — and one of Businelle’s health apps to measure sleep/wake activity and smoking patterns and cravings. “We will be able to see how getting mistimed sleep or short sleep affects cravings and withdrawal the next day,” Gamble said. The final stage of the study will enroll 50 smokers, who will come into a UAB lab for measurement of their craving and withdrawal symptoms after acute sleep restriction (four hours of time in bed) and after sleep extension (10 hours of time in bed).

“If successful, the results of this study will result in identification of circadian dysfunction and insufficient sleep as mechanisms that underlie the association between sleep and cigarette-smoking behaviors and dependence in diverse populations,” Cropsey and Gamble wrote in their grant proposal. “Moreover, these findings are likely to inform clinicians of the importance of sleep and sleep timing on cigarette-smoking behaviors and dependence that will help in the development of novel interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by tobacco use.”