In the past five years, clinical trials activity at UAB has more than doubled. Here’s how this phenomenal growth happened — and what it means for Alabamians.

In January 2020, the health news site STAT identified the most important new drugs of the 2010s based on the impact they had in medicine and on society at large. Alabamians had early access to the majority of these transformative therapies: seven of the 10 underwent at least part of their clinical testing at UAB.

A few months later, the university’s researchers were among the first in the country to begin clinical trials of what is surely one of the most eagerly discussed and anticipated drugs of the new decade so far: remdesivir, the first treatment shown to have a significant effect on outcomes for patients with COVID-19. “Our prior experience conducting clinical trials was essential to be chosen as a site,” said Paul Goepfert, M.D., professor of medicine and microbiology at UAB and director of its Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic. Another major factor was Jeanne Marrazzo, M.D., professor and director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at UAB, who holds a national leadership role with the National Institute of Health’s Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units. “That was critical in our being selected as a site,” Goepfert said.

One of the participants in the successful remdesivir clinical trial at UAB talks about his experience in this video.

The remdesivir trial was the first of several clinical trials of potential treatments for COVID-19 that opened rapidly at UAB in response to the global pandemic. In early April, patients at UAB Hospital were some of the first in the world to receive inhaled nitric oxide as a rescue treatment for severely damaged lungs in COVID-19 cases. “UAB was the second site to start recruiting patients and is the second largest contributor after the primary site, Massachusetts General Hospital, in this international, multicenter, randomized clinical trial,” said Pankaj Arora, M.D., assistant professor in the UAB Division of Cardiovascular Disease and principal investigator of the trial at UAB.

“UAB is the most important research-intensive institution in the Deep South, so the burden of disease and translational research rests in large part on our shoulders. We have the responsibility and what I think is a unique opportunity — to lead our country by finding better ways to treat the conditions that affect so many in our region.”

— Selwyn Vickers, M.D., senior vice president and dean of the School of Medicine.The trial builds on more than a decade of nitric-oxide research, and five other clinical trials, by Arora. UAB’s selection to take part in the trial was also “due to the excellent research infrastructure and support from the Center for Clinical and Translational Science, the vigilant and swift UAB Institutional Review Board and our respiratory care clinicians,” Arora added. “Their resolute efforts helped bring a potentially life-saving therapy to our patients at UAB.”

Since that inhaled nitric oxide trial launched, “multiple pharmaceutical and device companies have shown interest in UAB as a clinical research hub,” Arora said — and a major industry grant is moving forward to evaluate nitric oxide in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients.

Meanwhile, leaders in the UAB School of Medicine launched an urgent COVID-19 research grants program to accelerate UAB investigators’ search for new treatments and diagnostic tools to combat the epidemic. (Goepfert received funding to direct a biospecimen repository to enable clinical research projects.) This program led to clinical trials of potential therapies for the life-threatening cytokine storm syndrome seen in COVID-19 patients as well as convalescent plasma therapy to transplant effective antibodies from recovering patients to people struggling to overcome the disease.

The UAB attributes that ensured that Alabama patients were some of the first in the world to benefit from the latest COVID-19 treatments are the same ones that have allowed the university to more than double its clinical trials portfolio during the past five years: researchers with international reputations, a strong track record of previous trials success and an institutional commitment to advancing innovation.

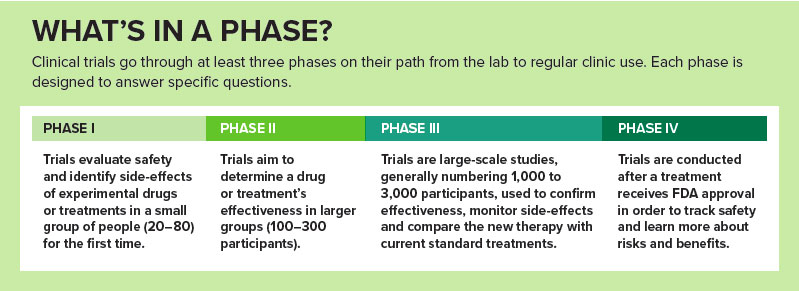

Steven Rowe, M.D., who received urgent COVID-19 research grant funding from UAB to develop new models for lab testing of the novel coronavirus, was able to leverage his prior work doing the same for the genetic disorder cystic fibrosis, for example. Rowe, professor in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine and director of UAB’s Gregory Fleming James Cystic Fibrosis Research Center, is intimately familiar with the No. 2 drug on STAT’s list, Trikafta. He helped lead Trikafta’s pivotal Phase III trials, which were conducted at 115 sites in 13 countries. The success of those trials spurred the drug’s FDA approval in October 2019 — unusually, this happened remarkably quickly, “even before the final results were presented at a scientific meeting,” Rowe said. In an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine in November 2019, published alongside the study report by Rowe and other investigators, NIH Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., explained that Trikafta’s triple-drug combination could bring “safe and effective molecularly targeted therapies to 90% of persons with cystic fibrosis.… This should be a cause for major celebration.”

It certainly was, Rowe said. “Immediately, patients were calling us to try to get on it,” he recalled. “It was an extremely busy and exciting week.” Many of Rowe’s patients already had experienced the benefits of Trikafta by then, however. “The Phase II results had already been out and digested and looked really exciting, so when Phase III opened, we tried to enroll as many people who qualified and were interested as possible,” he said.

Portfolio has doubled

More patients than ever have access to life-changing therapies at UAB. An intentional, institutionwide effort has led to the doubling of UAB’s clinical trials portfolio during the past five years, said Robert Kimberly, M.D., senior associate dean for clinical and translational research in the UAB School of Medicine and director of the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS). “We are an integrative academic medical center, and that means our goal is to take translational science to the bedside,” Kimberly said. “We have the opportunity to offer treatments to patients that might not be available to them otherwise.”

Some 900 clinical trials are enrolling patients at UAB, which include the latest innovative drugs and other treatment strategies for the conditions that most affect Alabamians. Each year, Blue Cross Blue Shield publishes an index of the diseases and conditions making the greatest impact on the health of each state’s residents. Trials ongoing at UAB address every one of the top 10 conditions listed for Alabama in the 2019 report. (See “Solutions to Alabama’s biggest health problems.”)

“This is really an exciting time,” said Dana Rizk, M.D., professor in the Division of Nephrology and medical director for the Clinical Trials Administrative Office (CTAO) in the School of Medicine. “There is interest in clinical trials that is unprecedented in my short career at least.” That is because new therapies are transforming treatment of many diseases, including kidney disorders. “We’ve always treated kidney disease with immunosuppressants, for example, but now we’re able to be more specific and targeted,” Rizk said. She was appointed CTAO medical director due to her success leading clinical trials efforts in the nephrology division, where active trials soared to more than 30 in 2019 from six in 2015.

A national leader

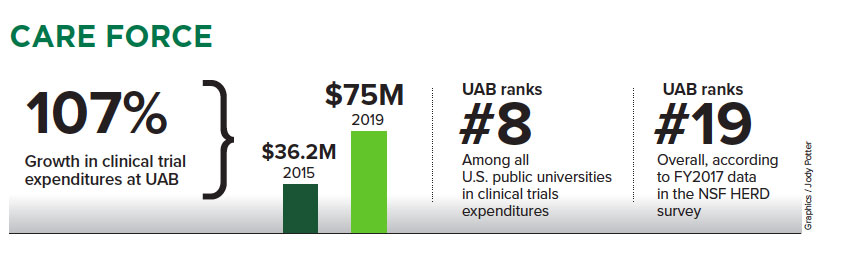

Between fiscal years 2015 and 2019, clinical trial expenditures at UAB rose 107 percent, to $75 million from $36.2 million. How does that compare nationwide? According to FY2017 data from the National Science Foundation’s HERD survey, which reports research and development expenditures at 915 institutions in the United States, UAB ranks No. 8 among all public universities in clinical trials expenditures and No. 19 overall.

“It’s a good story; across 112 public institutions, we’re in the top 10,” said Jason Nichols, O.D., Ph.D., associate vice president for research engagement and partnerships at UAB.

UAB’s position as a leader in clinical trials is fitting “because of where we sit in the national health care landscape,” said Selwyn Vickers, M.D., senior vice president and dean of the School of Medicine. “UAB is the most important research-intensive institution in the Deep South, so the burden of disease and translational research rests in large part on our shoulders. We have the responsibility and what I think is a unique opportunity — to lead our country by finding better ways to treat the conditions that affect so many in our region.”

In December 2019, the month after Rowe’s hectic November with Trikafta, oncologist Luciano Costa, M.D., Ph.D., had a similarly dramatic experience during the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. Costa, an associate professor in the Division of Hematology & Oncology, is medical director of the Clinical Trials Office at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB. He was presenting the results of an innovative “response-adapted” trial, known as MASTER, in patients with multiple myeloma. Participants saw rapid, impressive responses to the quadruplet therapy being tested, Costa announced. In fact, it was the “highest and deepest response rate ever reported in a myeloma trial,” despite being conducted in a higher-risk population, Costa said. Then he switched to a slide showing the characteristics of study participants: 21% were ethnic minorities, a massive success compared with most trials, which struggle to enroll underrepresented groups. An audience member, an African American oncologist from Indiana, pointed to those numbers and asked for another round of applause. The audience responded with a standing ovation. “I choked up,” Costa recalled. “I told my wife, who is also an oncologist, ‘I don’t know what is going to happen in the future, but career-wise, this is the highlight,” he said.

“There are many aspects of cancer research, but clinical trials are the ones most tangible to the people we serve,” Costa said. “That’s really where patients get first-hand interaction with the research mission of the institution and where we can make an immediate impact on their health. There is great data that shows that patients in clinical trials do better than patients who are not in trials. And with UAB being the longest-established Comprehensive Cancer Center in the Deep South, we have a unique opportunity, and a unique charge, to promote and advance clinical trial participation among minority groups. We have a collective mission here to improve those numbers.”

More patients than ever have access to life-changing therapies at UAB, which ranks in the top 20 nationally among all universities in expenditures on clinical trials.

More patients than ever have access to life-changing therapies at UAB, which ranks in the top 20 nationally among all universities in expenditures on clinical trials.

Team effort

The growth in clinical trials at UAB during the past five years represents a coordinated effort, from President Ray Watts, M.D., on down, Kimberly said. Watts, a neurologist specializing in Parkinson’s disease, has participated in a number of notable clinical trials himself. In the mid 2000s, while he was chair of UAB’s Department of Neurology, Watts led a sizable study in 50 sites in the United States and Canada for a new drug, rotigotine, that showed the medication was effective for treating tremors, muscle rigidity and other symptoms in patients with early-stage Parkinson’s disease.

In clinical trials, like college athletics, success depends on having a national reputation and a knack for recruiting. For decades, UAB researchers have been leaders in notable trials for a host of diseases, helping to set the global research agenda in genetics, heart disease, cancer, autoimmunity and infectious diseases.

The CCTS, which facilitates clinical trials at UAB, started a systematic plan in 2013 to enlarge the institution’s trials portfolio even further, Kimberly noted. Two years later, Nichols, a successful trialist specializing in ocular surface diseases, was selected for a newly created role overseeing research engagement and partnerships across UAB. The position was designed “to really look at our industry portfolio and focus on improving our processes to make them more efficient,” Nichols explained. “We’re the gateway to industry coming in to UAB.”

In 2016, UAB launched the Clinical Trials Initiative, led by Kimberly, Nichols and Mark Marchant, director of the Clinical Trials Administrative Office, to further increase UAB’s national visibility, streamline processes, expand the number of active trialists and prepare a new generation of investigators and staff to propel UAB’s tradition of trials success. Here are some of the significant elements behind that effort.

7 STEPS TO MORE TRIALS

1. Accelerating to stay ahead

Efficiency is crucial in today’s ultra-competitive funding environment, Nichols said. “Sponsors keep metrics on performance — how fast we turn projects around and how we recruit,” he said. “From the point we get a call to when we enroll the first patient, it’s the faster the better. We’re often in competitive enrollment scenarios and we want to see patients as fast as we can so that we can ensure we can bring new therapeutic options to Alabamians.”

Part of Nichols’s role is to demonstrate to industry partners that a large academic medical center can be as responsive as private physician practices, an alternative venue for clinical trials. “Sometimes there’s a perception in industry that it’s difficult to work with academia,” Nichols said. “The problem is practices don’t have the diversity and severe disease that we do. In addition to our responsibility to care for Alabamians, we have a reputation and recognition factor that is important in establishing credibility in the regulatory process. Many times, especially with some of the smaller companies, quick results are very important. Our job is to help them see that we can respond along those lines.”

“Time is the coin of the realm when it comes to clinical trials,” said Christopher Brown, Ph.D., UAB vice president for Research. “That is the measure we use to gauge our efficiency in research administration — are we making things faster and easier for faculty and staff?”

Between fiscal years 2015 and 2019, awards for industry-supported clinical trials at UAB rose 42%. In 2019, UAB expended $39,212,047 on 180 federally sponsored clinical trials and $35,787,319 on 1,127 industry-sponsored trials. “By percentage, industry trials are the largest area of growth in our overall research portfolio, although federal awards continue to grow as well,” Nichols said.

ss

2. Digitizing unlocks discoveries

Every night, UAB Health System’s electronic health records are backed up to an enterprise data warehouse for safekeeping. That information, protected and anonymized, also goes into a software tool known as i2b2, introduced to UAB by the CCTS, where it can be searched by researchers here and by approved investigators from other institutions. TriNetX, a startup from the University of California San Francisco, saw another way to use these i2b2 databases at large academic medical centers: improving recruitment to clinical trials.

“Recruitment is one of the major issues in clinical trials,” Kimberly explained. As a part of the Clinical Trials Initiative, UAB was an early adopter of TriNetX. When a pharmaceutical company or other industry sponsor is seeking to start a new clinical trial in a certain patient population, TriNetX can provide objective information on the institutions most likely to be able to recruit the patients needed to make that trial statistically feasible. “There’s a way, while fully protecting all patient health information, for TriNetX to find out how many patients we have meeting certain demographics,” Kimberly said. “They send a query in, and we never send anything but a number out.”

“Recruitment is one of the major issues in clinical trials,” Kimberly explained. As a part of the Clinical Trials Initiative, UAB was an early adopter of TriNetX. When a pharmaceutical company or other industry sponsor is seeking to start a new clinical trial in a certain patient population, TriNetX can provide objective information on the institutions most likely to be able to recruit the patients needed to make that trial statistically feasible. “There’s a way, while fully protecting all patient health information, for TriNetX to find out how many patients we have meeting certain demographics,” Kimberly said. “They send a query in, and we never send anything but a number out.”

The system “has been a major success,” Kimberly said. “We get offers of seven new clinical trials every month coming from TriNetX,” he noted. The clinician specializing in that area “may say, ‘I’m not interested,’ but nearly half of the trials we are offered we are able to participate in.”

Another important new collaborative initiative, developed by the NIH, is the Trial Innovation Network, which works through Clinical and Translational Science Awards hubs such as UAB’s CCTS. “The TIN can help with study design, with recruitment, with institutional review,” Kimberly said. It also brings together potential study sites. One way is through a tool called Accrual to Clinical Trials, which like TriNetX uses i2b2-driven clinical information to home in on the best sites for federally funded studies.

“TriNetX and TIN both represent new ways in which trial opportunities are coming to large health-provider organizations,” Kimberly said. “This is a way to use what we have built in i2b2 to enable us to participate in trials generated across the nation.”

3. Success breeds success

“Clinical trials are part of the engine that drives this medical center,” said Richard Whitley, M.D., Distinguished Professor in the departments of Pediatrics, Microbiology, Medicine and Neurosurgery and associate director for drug discovery and development in the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. Trials conducted in Birmingham pull all of medicine forward, Whitley added. Studies conceived at UAB have changed the treatment paradigm for babies with cytomegalovirus (CMV) born with hearing impairments and infants with neonatal herpes, “and those are just two of many examples in which studies done at UAB have changed the standard of care,” Whitley said.

Whitley, a renowned expert on infectious diseases, established the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group, funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. A partnership among more than 50 academic medical centers in the United States, Canada, England and Sweden, CASG is dedicated to performing clinical trials for medically important viral diseases in children and adults. “What we’re really trying to do is novel things that industry would not want to take on,” Whitley said. He mentions a study by his UAB Pediatrics colleague Professor David Kimberlin, M.D., to rapidly identify infants who have acquired the herpes simplex virus from their mothers. Babies with disease localized to the skin are currently treated intravenously with the antiviral drug acyclovir in the hospital for 14 days, then switched to an oral version of the drug and sent home. “They’re better in 72 hours,” Whitley said. “So, can we switch earlier? That would save families and insurance thousands of dollars and avoid hospital-acquired infections.”

Whitley’s reputation, and UAB’s, resulted in a $37.5-million award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to the Antiviral Drug Discovery and Development Center at UAB in 2019. This means UAB will have a major role in development and, ultimately, testing of new treatments for influenza, dengue, Zika, MERS and other high-priority infections, including eventual clinical trials. “This institution is incredibly good to its investigators,” Whitley said. And with that support, “academic egghead investigators like ourselves” can establish the expertise and credibility to shape the future course of research, he added.

“It helps to be known in a particular area,” said Kenneth Saag, M.D., a professor in the Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology. “You develop a reputation as an expert in a particular discipline and class of agents and one thing leads to another.”

Like Whitley, Saag is historically one of the most prolific trialists at UAB. “One of the things I’ve been successful in is getting involved in high-visibility studies,” Saag said. He has had three first-author papers in the New England Journal of Medicine, all focused on osteoporosis therapies. These studies led to the approval of new treatment approaches. Just as important, one study of a biologic drug revealed safety concerns for certain patients, which led to an FDA warning and has allowed doctors to tailor their use to the most appropriate populations. “It’s important for us to be successful,” Saag said. “If we do a good job, recruit well, deliver high-impact publications and take the lead in designing studies and interpreting results, we become the thought leaders and the national experts in a particular area; then, when they do the next drug, they come to you. Having the skills and experience and institutional resources to do these trials really sets us apart and gives us visibility.”

Studies conceived at UAB have changed the treatment paradigm for babies with cytomegalovirus born with hearing impairments and for infants with neonatal herpes — just two of many examples in which studies done at UAB have changed the standard of care.

Studies conceived at UAB have changed the treatment paradigm for babies with cytomegalovirus born with hearing impairments and for infants with neonatal herpes — just two of many examples in which studies done at UAB have changed the standard of care.4. Reevaluate everything

In 2018, UAB’s Clinical Trials Administration Committee was created at the direction of President Watts. “CTAC draws people from each school, both investigators and administrators,” Kimberly said. “The goal is to identify areas where we need to focus attention, such as new processes or policies from the NIH and other funders, or sources of inefficiency internally. When we do see a speed bump, the committee develops detailed action points to solve the problem.” It is important that the CTAC “was created from the president’s cabinet, with the president’s signature,” Kimberly said. “That demonstrated to everyone — from investigators to patients — that this is an institutional commitment.”

A similar commitment is OnCore, the first universitywide, electronic clinical trials-management system adopted at UAB. OnCore, which was launched in 2017, also at Watts’ direction, consolidated separate systems into a single tool for operations management, billing compliance, reports and analytics. The implementation included creation of master charge lists to harmonize billing, a process that has involved a heroic amount of effort, Kimberly said. “This is the first time this has been done. In fact, there are a lot of first-time evers that we have accomplished as a part of this initiative,” he said.

5. SHARe-ing the load

UAB has a “long and successful history of good community relationships that allow us to assemble large cohorts for analysis in cancer, cardiovascular disease and beyond,” said Bruce Korf, M.D., Ph.D., chief genomics officer for UAB Medicine. “You can’t do that without the trust of the community.” Korf himself is the principal investigator of the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium, funded by a $9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, which tests medications to prevent or treat complications of these genetic disorders. Korf also is leading two major studies — the Alabama Genomic Health Initiative (AGHI) and the All of Us Southern Network, part of the NIH’s All of Us Research Program — that have enrolled tens of thousands of Alabamians and are setting the stage for introduction of personalized, genomic medicine to the general population. Although neither is itself a clinical trial, AGHI is preparing to spin off two pilot trials of return of results of genomic studies in 2020 and more are sure to follow. In October 2019, UAB was awarded an additional $7 million from the NIH to conduct a pilot study to discover better ways to engage and retain participants in the All of Us Research Program.

“It’s our responsibility that everyone has the opportunity to participate in clinical trials and see the benefit,” Kimberly said. To increase these opportunities in the Deep South, UAB has taken the lead in developing the Southeast Health Alliance for Research, known as SHARe, which brings together 13 institutions in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. “Our goal is to have a regional clinical trial consortium; to get in the place where NIH and industry can come to us and say, ‘We need to make sure we have appropriate representation for our clinical trials,’” Kimberly said.

UAB leads the All of Us Southern Network, part of the NIH’s All of Us Research Program, which has been a leader in enrolling underrepresented patients in an ambitious effort to improve precision medicine for all Americans.

UAB leads the All of Us Southern Network, part of the NIH’s All of Us Research Program, which has been a leader in enrolling underrepresented patients in an ambitious effort to improve precision medicine for all Americans.

6. Enhancing research support

Ken Saag has 19 trials running, including industry-initiated trials of therapeutics, investigator-initiated studies and behavioral studies. That kind of productivity is only possible with a lot of help, he noted. “One of the things that UAB has allowed me to do is put together a good team,” Saag said. “With more regulation and oversight, it’s gotten more expensive to do clinical trials. You need study coordinators, recruitment coordinators, informed consent, budgeting.”

Busy clinicians can be daunted by the paperwork and other requirements of trials, says Dana Rizk. She eased that burden by making herself the first point of contact. “If a sponsor was interested in the UAB nephrology division as a site they would come to me and an administrator and we would do the upfront work,” Rizk said. “Depending on the subject we would identify investigators in the division who were interested. Then if they said yes, we would take it all the way until it was ready to start, then turn it over to the investigator. And even past that point we would continue to keep an eye on performance, enrollment and billing.” The effort was particularly effective with young investigators. “We could say, ‘Here’s a study that might be of interest to you and we’ll take care of all the paperwork,’” Rizk said. “‘You just do the clinical work that is for the most part nearest and dearest to your heart.’”

In time, “we got more and more buy-in from investigators and certainly a lot of interest from industry, because they only had to deal with point persons who could navigate the system,” Rizk said.

When Luciano Costa arrived at UAB in 2014, he led a focused effort to increase clinical trials activity in myeloma. “We had excellent physicians taking care of myeloma patients, but very little going on in terms of clinical trials,” Costa said. Between 2013 and 2019, annual accrual of patients leapt from 0 to 85 per year. “We beat the bushes to try to get the right opportunities and clinical trials,” Costa said. “We put an emphasis on Phase I first-in-human trials, where the innovation is, and on creating our own concepts. When you have a coordinated team effort and motivated investigators you can accomplish big things.”

In 2019, Costa was appointed medical director of the cancer center’s Clinical Trials Office. He created an orientation program for its new faculty to help instill a culture of innovation and collaboration across the center. Working groups in cancer subtypes enable senior investigators to mentor younger colleagues. “It’s helping to show the way, without being condescending or patronizing,” Costa said. “We all have walked those paths before and, just like in any profession, when you set the right culture it quickly and easily rubs off.”

Costa feels this is the fastest way to improve care. “Clinical trials are essential to develop new therapies, but in this country less than 5% of cancer patients participate in a clinical trial,” he said. “Plenty of research, and my personal experience, is that the most important factor for a successful clinical trial accrual is the motivation of the investigator. When patients come to us they are full of hope that we can offer them something better, something unique. When they see our enthusiasm to find new treatments, that has more impact than anything.”

The O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB has emphasized phase I “first-in-human” clinical trials.

The O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB has emphasized phase I “first-in-human” clinical trials.7. Priming the pipeline

The relentless competition for clinical trials means “we need to continually look for ways to innovate in our institution in terms of ways we operate,” said Mark Marchant, CTAO director. Sometimes, UAB has to turn down trials because its veteran investigators don’t have the bandwidth to take on more, Kimberly noted. The added volume also drives a constant need to recruit and train staff to keep the trials running.

One of Dana Rizk’s chief duties as medical director of the CTAO is “to groom the next generation of researchers,” she said. “The hardest thing for a young investigator is to get started doing industry-sponsored trials. The sponsor may be interested in UAB because we have a large patient population or because we are in a part of the country with under-represented minorities. There are many reasons to come, but first they want to know you can hit the ground running.”

Rizk is working with staff in the CCTS to extend its current Clinical Investigator Training Program, which helps faculty who are new to clinical trials “learn what’s your responsibility as an investigator, how do you start the whole process and everything else you need to know,” she said.

Another CCTS training initiative, the Research Training Program, is a six-week bootcamp for staff. Learners hear from 27 campus experts on everything from research ethics and budgeting techniques to institutional review board protocols and strategies for increasing recruitment and retention in trials. Many participants “come from a nursing background,” said Meredith Fitz-Gerald, director of the CCTS Clinical Research Support Program. “We’re also seeing a shift to non-nurse coordinators as well.” The training program, which often has a waiting list for its twice-yearly sessions, gives participants “contacts with leaders across campus,” Fitz-Gerald said. “That gives them mentors in the form of experienced managers in all the areas of specialty in clinical trials.”

In order to build up the pipeline of nurse study coordinators, Marchant has established links with the UAB School of Nursing. Honors students now shadow study coordinators so they can get a taste of the benefits of the work. To improve recruitment and retention of clinical research staff, UAB also is launching a new career-ladder program, with job categories and titles standardized across the institution, to give staff “a clear-cut path forward in terms of how they can advance their career at UAB,” Marchant said.

An ‘exhilarating’ moment

The thrill of taking part in life-changing discoveries makes clinical trials endlessly rewarding, investigators say. Kimberly, whose research interest is in autoimmune diseases, has had several such moments. “When I first came to UAB in the 1990s we were one of the few institutions in the country that did studies of etanercept [Enbrel], a biologic drug used for rheumatoid arthritis,” Kimberly said. “That was the first-to-market product in this whole space for autoimmunity treatments for lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and cancer. It is still used and there are now more than 550 therapies in this area. That could not have happened without clinical trials, without the patients and the providers and industry, too. Our patients were among the first in the country to get access, and those therapies revolutionized the field.”

Kimberly said the same thing is happening today with the development of checkpoint inhibitors in oncology that unleash the immune system against cancer. “It’s one of the privileges of medicine to see and participate directly in the development of really important new therapies that completely change the impact of a disease.”

“I wanted to do something that moves the needle.”

“I wanted to do something that moves the needle.” “It makes you want to get up in the morning and come to work.”

“It makes you want to get up in the morning and come to work.” “Simply put, it is a game changer.”

“Simply put, it is a game changer.”