A first-of-its-kind study, funded by the urgent COVID-19 research grants program from UAB, aims to identify the largest contributing factors to COVID-19 disparities in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana — and identify the geographic areas where testing sites and other resources are most needed.COVID-19 is not an equal-opportunity disease. Black people are infected by the virus at four times the rate that their proportion of the overall population would suggest, and they are twice as likely to die from it. Similar disparities exist in other racial and ethnic minority groups.

A first-of-its-kind study, funded by the urgent COVID-19 research grants program from UAB, aims to identify the largest contributing factors to COVID-19 disparities in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana — and identify the geographic areas where testing sites and other resources are most needed.COVID-19 is not an equal-opportunity disease. Black people are infected by the virus at four times the rate that their proportion of the overall population would suggest, and they are twice as likely to die from it. Similar disparities exist in other racial and ethnic minority groups.

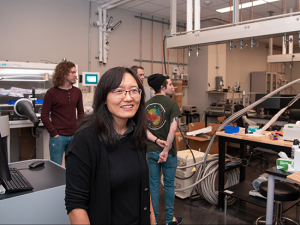

But race and ethnicity are not the discrete risk factors responsible, said Gabriela Oates, Ph.D., a social epidemiologist and assistant professor in the Division of Pediatric Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine. "When we report that Blacks, for example, have higher risk of death from COVID, is that due to biological race? No, it isn't," she said. “As a social construct without genetic basis, race cannot be a risk for COVID-19 infection or mortality. Instead, the disparity is due to unequal socioeconomic conditions, including higher rates of service-sector employment, residential crowding, and poverty in communities of color. It is also due to increased prevalence of obesity, diabetes and other chronic diseases among the socioeconomically disadvantaged.” Yet some factors are likely to be more important than others. Which ones? And how are the people most affected by these crucial factors distributed across neighborhoods and wider geographic areas across the Deep South?

These questions are the subject of a new project funded through the second round of UAB's urgent COVID-19 research grants program, with Oates as principal investigator. The study will use extensive testing and diagnosis data from state health departments in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, along with clinical information from UAB Hospital and other large medical centers in those states.

First-of-its-kind study is untangling intertwined factors

This summer, UAB's Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center (MHRC) has conducted community-based COVID-19 testing in under-served areas across Jefferson County. By going a step further and disentangling race, clinical comorbidities and socioeconomic conditions, the investigators aim to give public health departments and other entities crucial data on where to invest their resources, Oates said. Results from the new project could help inform locations for future testing sites in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Data from the study could guide "optimal deployment of vaccinations and antiviral therapeutics" as well, as the team wrote in its project proposal.

The study will be the first to analyze "COVID-19 data along multiple dimensions of inequality to clarify how racial, socioeconomic, environmental and spatial factors are intertwined in their contributions for observed COVID-19 disparities," the investigators explained. The team involves scientists and clinicians across the Deep South. In addition to co-principal investigators Gerald McGwin, Ph.D., Mona Fouad, M.D., and William Curry, M.D., from UAB, the team includes researchers from the University of Mississippi Medical Center (William Hillegass, M.D., Ph.D., and Sheeba Ogirala), Louisiana State University Health Center (Lucio Miele, M.D., Ph.D., and Denise Danos, Ph.D.), Pennington Biomedical Research Center (Ronald Horswell, Ph.D., and San Chu), and Ochsner Health System (Daniel Fort, Ph.D.)

Finding patterns across the map

Oates's research investigates the impact of demographic, socioeconomic and environmental factors on outcomes in chronic diseases. This work often involves mapping residential addresses to data from the U.S. Census and other publicly available databases in order to identify spatial patterns in health outcomes. In a 2017 research article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Oates and co-authors compared patterns of 12 chronic diseases, including obesity, diabetes, cancer, asthma and depression, and health-related behaviors such as smoking and physical activity, in the Mid-South region and the rest of the country. They noted that the Mid-South states had increased rates of chronic disease and worse health-related behaviors than the rest of the U.S. population. Their study also identified specific subgroups at increased risk for chronic health conditions.

|

“As a social construct without genetic basis, race cannot be a risk for COVID-19 infection or mortality. Instead, the disparity is due to unequal socioeconomic conditions, including higher rates of service-sector employment, residential crowding and poverty in communities of color. It is also due to increased prevalence of obesity, diabetes and other chronic diseases among the socioeconomically disadvantaged.” |

In the present COVID-19 study, Oates and her co-investigators are analyzing a vast amount of data. From the state health departments in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana they are obtaining statistics on testing, positive and negative tests and diagnosed cases of COVID-19 by Census tract of residence from Feb. 1 to Aug. 31, 2020. The researchers also have data on COVID-19 patients treated at the UAB Health System, University of Mississippi Medical Center, and Ochsner Health, geocoded to residential Census tracts. They will combine and analyze these data to determine the independent contributions of patient demographics (age, sex, race), comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, tobacco use and a number of chronic diseases), and neighborhood socio-environmental exposures (socioeconomic deprivation, rurality, food access and health care access) to COVID-19 disease severity and outcomes. These COVID-19 outcomes include hospitalizations, length of stay and mortality.

"We need to know the relative contributions of all risks: biological, clinical, social, economic and place-based," Oates said. “This will allow us to see COVID-19 disparities in a broader context rather than through the lens of biological determinism.” It is important that these data are available across all three states, she added. "Both geographically and demographically, our states are quite similar. We want to look at the region as a whole and then also look for differences by state."