Philosopher Lindsay Brainard, Ph.D., studies "the tools modern scientists use when they need to come up with new hypotheses," including computer simulations.As Batman movies go, 1992’s “Batman Returns” — the first sequel to Tim Burton’s original 1980s smash, with Michael Keaton returning and Michelle Pfeiffer co-starring — was one of the weakest at the box office. But it has a unique place in science history.

Philosopher Lindsay Brainard, Ph.D., studies "the tools modern scientists use when they need to come up with new hypotheses," including computer simulations.As Batman movies go, 1992’s “Batman Returns” — the first sequel to Tim Burton’s original 1980s smash, with Michael Keaton returning and Michelle Pfeiffer co-starring — was one of the weakest at the box office. But it has a unique place in science history.

It is all thanks to a short scene in which an army of computer-generated penguins led by Danny DeVito’s Penguin character spreads out through Gotham. The software that made the penguins’ realistic flocking behavior possible was developed by a computer animator and special-effects artist named Craig Reynolds. In the late 1980s, working toward the final product that would appear in “Batman Returns,” Reynolds created Boids, a computer simulation that accurately captured the dynamics of animal flocking using a few simple rules.

At the time, scientists had spent decades debating how birds and other animals perform feats of synchronized behavior. Starlings, for instance, can gather in groups of up to 750,000 individuals yet manage to swoop and swirl on a timescale measured in fractions of a second. To pull this off, scientists thought, there must be a leader bird directing the operation somehow. That is, until Reynolds’ simulation revealed that the behavior could be replicated by giving each individual “boid” three basic guidelines for maintaining spacing and speed.

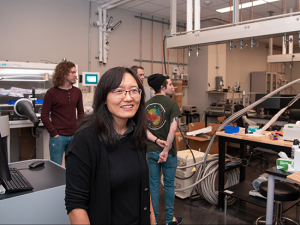

Before Reynolds’ simulation, the hypothesis that flocking was leaderless was not taken seriously by scientists, explains Lindsay Brainard, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the College of Arts and Sciences Department of Philosophy. When they saw his computer model, however, scientists could see how it was possible. The simulation “was able to correct for a failure of imagination,” Brainard said. (Read her paper, How to Explain How-Possibly, for more on Boids — and basketball.)

Tools to think differently

Brainard specializes in the philosophy of science. Philosophers of science separate scientific work into two categories. “There is discovery, where scientists develop a hypothesis, and justification, where they gather evidence to support that hypothesis,” she said.

Philosophers of science separate scientific work into two categories. “There is discovery, where scientists develop a hypothesis, and justification, where they gather evidence to support that hypothesis,” Brainard said. Most philosophers of science focus on justification, but Brainard is more interested in discovery. “I am interested in how ideas come into being.”

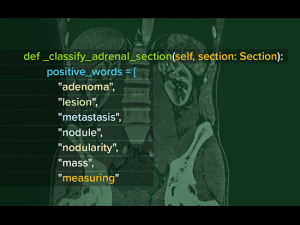

Most philosophers of science focus on justification, “but I find it really interesting to think about the tools modern scientists use when they need to come up with new hypotheses,” Brainard said. “I am interested in how ideas come into being.” She is particularly intrigued by “epistemically bleak situations, where we don’t really know a lot and where technology can be used to help.”

Advances in computing power have allowed scientists to build simulations of everything from the inner workings of cells to the birth of the universe. In 2013, three computational chemists won the Nobel Prize for their success in modeling blindingly fast and complex interactions such as protein folding. Nobel co-winner Arieh Warshel, Ph.D., noted that “computer simulations will increasingly become the key tool in modeling complex systems.”

Brainard is not primarily concerned with the code and technology behind these simulations. Instead, “I’m interested in how technology can be used when we have no idea what’s going on,” she said. “Before you can do an experiment, you need a hypothesis. Simulations can point the way forward when what you need is a creative theory.”

Seeing in new dimensions

Brainard joined UAB from Michigan’s Calvin University in August 2020. She says she is thrilled to have the opportunity to collaborate with philosophy department colleagues such as Marshall Abrams, Ph.D., who uses simulations to study topics in cognitive science and evolutionary theory. She also is eager to explore collaborations with scientists using computer models across campus.

UAB’s strong undergraduate programs in science and technology are a perfect match with philosophy, Brainard says. In particular, “many students studying the sciences get really excited about the philosophy of science,” she said. “If you are loving a field and want to ask questions the field itself doesn’t answer, like ‘what is evidence,’ then philosophy can be a perfect major. You learn the tools to interrogate the presuppositions and limits of your scientific discipline so you can see it in new dimensions.”

Brainard, a first-generation college student herself, consciously models possibility to the undergraduates in her classes as well. “First-gen students often feel like fish out of water, and I can certainly relate to that,” she said. “This world of higher education was brand-new to me. Students often don’t realize that there are all these campus resources — office hours, the writing center, etc. — that they can use to help them succeed. When I was a student, I never had a professor tell me they were first-generation. I’m always really up-front with students about that. I tell them, ‘I have a Ph.D. — there is no limit to how far you can go.’”