|

Gorgas Case 2021-02 |

|

|

The following patient was hospitalized in the Tropical Medicine ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital on February 24th, 2021.  History: A 34-year-old male patient presented with a 1-month history of intermittent intense holocranial headaches accompanied by nausea and occasional vomiting, followed one week later by fever to 38°C; both were relieved by acetaminophen. Two weeks prior to admission, he noticed the new appearance of a non-pruritic rash on his thorax, arms, and face. On the day of presentation to Cayetano Heredia Hospital, the nausea and vomiting had worsened, he had generalized weakness, asthenia, and diaphoresis. Epidemiology: Born and lives in Lima. Works in an electronics store. Multiple unprotected sexual encounters in the last months. No history of TB exposure. No previous STI or HIV tests. Past Medical History: Hospitalized for COVID-19 six months prior to admission. Physical Examination: BP:120/84, HR 120, RR 24, T 38°C. SatO2: 98% (FiO2 0.21). Skin examination revealed multiple skin-colored umbilicated papules, some with central necrosis, in varying sizes and painless, in face, thorax, genitalia and upper and lower extremities (Image A). Oral examination revealed white lesions in the buccal mucosa and soft palate. Chest and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. Neurological examination revealed nuchal rigidity. Fundoscopy was not performed. Imaging studies: Chest X-ray is shown in Image B. CT Scan of the brain was not performed. Laboratory: Hb: 13.3 g/dL; Hct. 40%; WBC 5 440 (neutrophils: 79%, eosinophils: 0.2%, lymphocytes: 16%); Platelets: 216 000. INR 1.21, PT 16.4, PTT 43.4. Gluc: 102 mg/dL, Urea: 34 mg/dL, Creat: 0.8 mg/dL, AST 39, ALT 21, GGT 51, Alk Phos 104, LDH 403, albumin 3.6. Serology for HIV 1-2 positive. Serology for HTLV-1 negative. AntiHBc, HBsAg, antiHbs non-reactive. RPR non-reactive. CD4 cell count and viral load determinations are pending. CSF: Xanthochromic, glucose 28, protein 32, no WBC, 300 RBC/mm3, ADA 6.15, opening pressure: 30 cmH2O

|

|

Diagnosis: Disseminated cryptococcosis in a recently diagnosed HIV patient

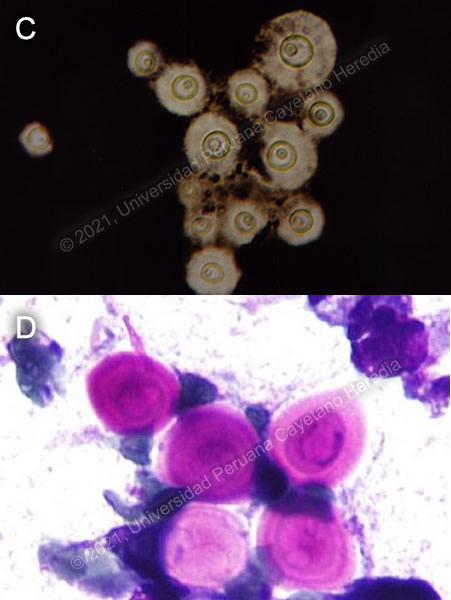

Discussion: A KOH stain of the patient’s CSF revealed multiple budding yeasts, and the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis was then confirmed by India Ink examination (Image C). Microscopy of a biopsy of a skin lesion also revealed typical Cryptococcus sp. yeasts (Image D). Latex agglutination test was unavailable. Cultures are underway. Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is the one of the most common causes of diffuse central nervous system involvement in HIV-infected patients. In our institution, CM is the second leading cause of admission in our institution, after tuberculosis; 234 patients with CM and HIV were discharged over a period of 13 years, 77% were males, mean age was 35 years, 24% had a previous episode of CM; median CD4 count was 33 cells/mm3, and only 17% were receiving ART (1). Disseminated cryptococcosis is defined by isolation of microorganisms from at least two different sites, or a positive lung culture. Skin lesions are typically associated with CNS disease and usually represent hematogenous spread. They may have different morphologies, including pustules, papules, ulcers, cellulitis, plaques, abscesses, or, as was seen in the presented case, umbilicated papules (Image A). The differential diagnosis for umbilicated papules in an immunocompromised patient also includes molluscum contagiosum, and other fungal infections such as histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis or, in the right geographical setting, talaromycosis. Diagnosis of CM relies on the isolation of Cryptococcus from suitable samples or antigenic testing. However, certain clinical features may make the diagnosis more likely. An opening CSF pressure of 25 cmH2O or more is found in more than half of patients with cryptococcal meningitis (2). This, in conjunction with the characteristic low CSF cell count, helps differentiate cryptococcal meningitis from other causes of CNS involvement such as syphilis, tuberculosis, or listeria. WHO recommends the use of a rapid diagnostic antigenic test, either a lateral flow assay or a latex agglutination test. If these tests are not available, then an India ink stain is recommended (3). While lumbar punctures (LP) are diagnostic and permit measuring the opening pressure, they may be contraindicated in cases of significant coagulopathy, suspected space-occupying lesion, or major spinal deformity. In resource limited settings where neuroimaging may not be available, the risk-benefit analysis favors performing an LP unless a clear contraindication exists, such as focal neurological signs or recurrent seizures (3). If an LP cannot be performed, then serum antigenic tests are recommended. If the results are negative, another diagnosis should be considered. Follow-up cultures are not indicated unless the patient is not responding to medical treatment. Serologic or CSF antigenic tests are not recommended to follow-up response to treatment. The cornerstones of the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in an immunocompromised patient are antifungal therapy, control of intracranial pressure, and immune recovery. Antifungal therapy should consist of an induction phase lasting two weeks, then consolidation therapy for eight weeks, and finally suppressive therapy for at least one year. WHO recommends first-line induction therapy with both amphotericin B and flucytosine for one week followed by one week of fluconazole (3). If flucytosine is unavailable, fluconazole may be used, though it does not have the same early fungicidal activity as the combination with flucytosine (4). A study to determine predictors for negative cultures at two weeks (early fungicidal activity) of induction therapy was conducted in our hospital (1).Two variables at baseline were associated with not achieving early fungicidal activity: high opening pressure (>35 cmH2o) and high fungal burden (4.5 log10 CFU/ml). After induction, patients should receive fluconazole for consolidation, and then a lower dose for suppression. Increased intracranial pressure should be managed aggressively with therapeutic lumbar punctures to achieve an opening pressure of less than 20cm H2O, or with drains. Diuretics and corticosteroids should not be used. The inpatient mortality in our hospital is 20%; 35% of these patients died in the first two weeks of treatment (1). Antiretroviral therapy should be started 2-10 weeks after starting antifungal therapy, to reduce the risk of IRIS. Our patient is currently receiving induction therapy with amphotericin B and fluconazole, with regular therapeutic lumbar punctures. References: 3. Guidelines for The Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Cryptococcal Disease in HIV-Infected Adults, Adolescents and Children: Supplement to the 2016 Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2021 Mar 12]. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531449/ |