|

Diagnosis: Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease). Multibacillary leprosy according to the WHO classification. Probable Borderline Lepromatous according to Ridley-Jopling classification.

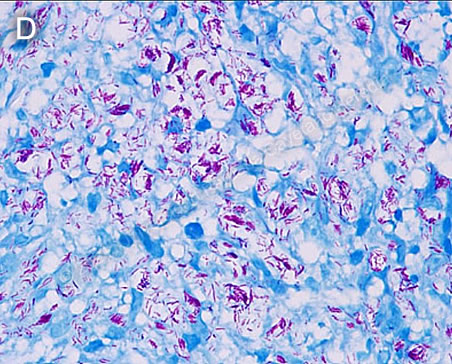

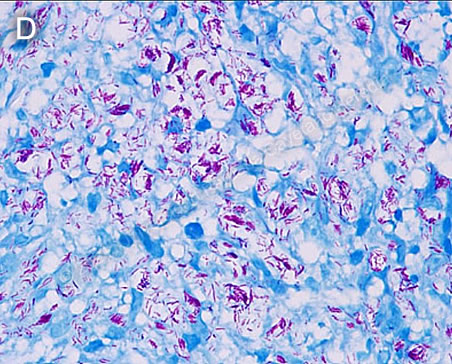

Discussion: Slit-skin smears were not performed for this patient. A skin biopsy of the lesions with Fite-Faraco staining revealed abundant acid-fast bacilli (AFB) corresponding to Mycobacterium leprae (Image D).

In patients who present with symptoms that are compatible with leprosy, slit-skin smears should be taken first, as they can be sufficient for diagnosis. Slit-skin smears are performed by making small slits (about 5 mm in length and 2 mm in depth) in pinched skin (to avoid bleeding), and then scraping the edges. Frequently sampled areas include ear lobes, the dorsal surface of the elbows and anterior surface of the knees. The obtained material is smeared on a clean slide, stained for AFB with a modified Ziehl-Neelsen, and examined microscopically. Bacilli can also be found in the nerves, though nerve biopsies are usually reserved for patients with subclinical or primarily neuropathic forms of leprosy. Our patient presented to our institution with the results of a skin biopsy performed elsewhere.

Skin biopsies, though helpful to determine the extent of involvement, are not essential to diagnosis. In fact, the diagnosis of leprosy can be made on the basis of one of three cardinal signs: definite loss of sensation in a pale or reddish skin patch, thickened or enlarged peripheral nerves with loss of sensation or weakness in the corresponding muscles, or presence of AFB in a slit-skin smear. In higher resource settings, PCR-based assays may be used to improve diagnostic accuracy, but they are not necessary for diagnosis. The clinical picture in the presented patient, then, was sufficient to make a diagnosis of leprosy.

Leprosy can present in various clinical forms depending on the host’s immune response, according to the Ridley-Jopling classification [1]. The spectrum of disease ranges from tuberculoid leprosy (TT), in which there are few or no AFB in the lesions and there is good cell mediated immunity, to lepromatous leprosy (LL), in which there are many AFB and poor cell-mediated immunity (as was the case with the presented patient). However, the 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines [2] recommend a different classification system, which categorizes cases of leprosy only as paucibacillary or multibacillary in order to guide treatment. Paucibacillary cases present with 1-5 skin lesions, and no bacilli in slit-skin smears. Multibacillary cases have either more than 5 skin lesions, nerve involvement, or demonstrated bacilli in slit-skin smears. These criteria make it easy to discern between the two types of leprosy and determine the best course of treatment even when slit-skin smears and biopsies cannot be performed.

LL typically presents with diffuse infiltration of the skin, and multiple mildly erythematous lesions that may or may not be hypoesthetic; in contrast to TT which presents usually with a single anesthetic macule or plaque. The most commonly affected nerves are the ulnar, median, lateral popliteal, posterior tibial, and facial nerves, which can become enlarged and cause regional patterns of sensory and motor loss. In LL, patients are typically described to have glove and stocking sensory loss due to compromise of small dermal sensory and autonomic nerves. Advanced neuropathies can lead to deformities as were observed in the described patient, including claw hand, footdrop, claw toes, and limb insensitivity, which in turn can lead to more damage due to burns and other daily trauma that goes unnoticed by the patient. Systemic symptoms can result from infiltration of mycobacteria in various anatomic structures [3]. In the presented patient, the nasal congestion could be attributed to infiltration of the nasal mucosa.

Borderline lepromatous (BL) patients present with innumerable small plaques that resemble hives; these lesions are not seen in lepromatous (LL) patients. The fact that this patient had pain and numbness on his hand, with posterior clawing and the presence of mildly burning “hives” suggests that he was having a type 1 reaction which is seen in borderline patients but not in LL patients. So-called type 1 reactions may occur in up to one-third of borderline patients. These reactions consist of inflammation of the skin lesions and/or the peripheral nerves. Clinically, the skin lesions swell up, become more erythematous, shiny, and warm, and new lesions may appear; additionally, the nerves become swollen and painful. Nerve function deterioration follows if untreated. Therefore, we think that these “non-pruritic hives” and the pain on the ulnar aspect of the hand were caused by a type 1 reaction and that this patient is best classified as borderline lepromatous, very close to the lepromatous end of the spectrum. Type 1 reactions are caused by increases in T-cell reactivity to M. leprae with infiltration of reactive CD4 cells into skin lesions and nerves. The edema and painful inflammation must be treated urgently with high-dose steroids in order to prevent further nerve damage. After treatment is completed, some patients may partially recover skin sensation, but longstanding nerve damage is irreversible. When starting therapy for these patients, it is important to warn them about the possibility of developing a type 1 reaction, so that the patient does not stop the therapy for leprosy thinking that it is producing the reaction.

The differential diagnosis for a patient with erythematous infiltrative skin lesions includes cutaneous sarcoidosis, mycoses fungoides, adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma caused by HTLV-1, diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, and scleromyxedema. However, leprosy is unique in that the lesions may have diminished sensory perception, and peripheral nerve involvement is usually found, which is not characteristic of any of the aforementioned conditions.

WHO recommends that treatment be started with a 3-drug regimen of rifampicin, dapsone, and clofazimine. Paucibacillary cases should be treated for 6 months, while multibacillary cases should be treated for 12 months. The US National Hansen’s Disease Program recommends longer courses of treatment to reduce relapses: 12 months of treatment with daily dapsone and rifampicin for patients with paucibacillary leprosy, and 24 months with daily dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine for patients with multibacillary leprosy. Rifampicin-resistant cases should be treated with at least two second-line drugs (clarithromycin, minocycline, or a quinolone) and clofazimine daily for 6 months, and then one second-line drug plus clofazimine for another 18 months. The possibility of adverse effects of dapsone and clofazimine should be considered, and a reference text should be consulted prior to initiation of therapy by anyone not familiar with these.

This patient will be treated with the multibacillary regimen recommended by WHO. The most common adverse reaction in multibacillary disease, occurring in about 50% of patients with lepromatous and borderline lepromatous leprosy, is a Type 2 reaction, which most commonly presents as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). ENL is considered an antigen-antibody immune complex deposition in the tissues, often accompanied by a severe systemic illness, and characterized by high levels of tissue and circulating TNF-α. ENL presents with fever and tender erythematous nodules [4], and may also produce, to varying degrees, neuritis, uveitis, myositis, dactylitis, periostitis, orchitis, lymphadenitis and nephritis accompanied by edema, arthralgia, and leukocytosis. It can occur in patients prior to, during, or after therapy, until the antigen load decreases markedly, and may present as repeated acute episodes or be chronic and ongoing. ENL can be treated symptomatically if mild or with prednisone or thalidomide if severe [see Gorgas Case 2011-04].

With proper treatment, the patient’s skin lesions may resolve within a few years, but the long-standing nerve damage is irreversible, and the resulting deformities will be permanent. Patients with sensitive deficits secondary to leprosy need to be taught to regularly evaluate and properly care for areas of loss of sensation to prevent further damage. They should also exercise extending their fingers to retain flexibility of the contractions.

In endemic areas, we usually examine the family contacts once a year for at least five years and advise them to contact the health system if they present any skin lesions or numbness.

References

1. Britton WJ, Lockwood DNJ (2004) Leprosy. Lancet Lond Engl 363:1209–1219

2. WHO SEARO/Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (2018) Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy.

3. Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ (2007) Leprosy. Clin Dermatol 25:165–172

4. Pocaterra L, Jain S, Reddy R, Muzaffarullah S, Torres O, Suneetha S, Lockwood DNJ (2006) Clinical course of erythema nodosum leprosum: an 11-year cohort study in Hyderabad, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74:868–879.

|