|

Diagnosis: acute fascioliasis by Fasciola hepatica

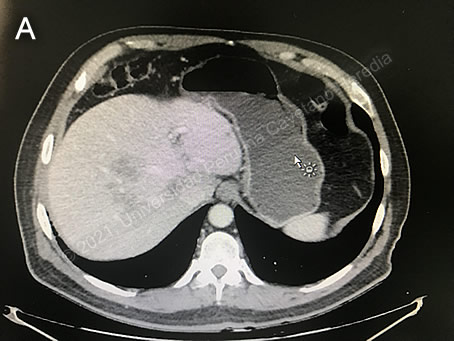

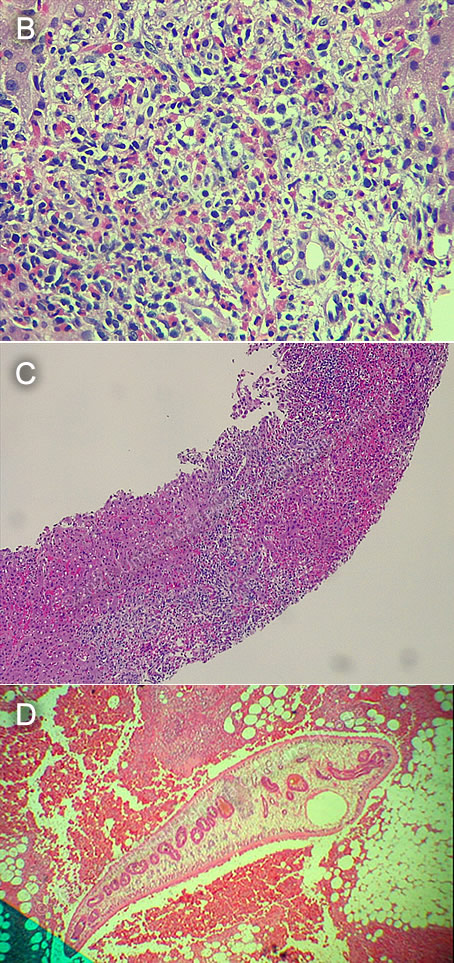

Discussion: The combination of exposure to raw vegetables, hypereosinophilia and hypodense lesions in the liver on the patient’s abdominal CT-scan were highly suggestive of acute fasciolasis. The liver biopsy showed a severe inflammatory reaction with a predominance of eosinophils; no parasites or malignant cells were identified (Images B and C). An IgG Fas2-ELISA was positive for Fasciola hepatica.

The differential diagnosis for eosinophilia with accompanying destructive hepatic lesions is very limited. Toxocariasis causes hypereosinophilia with hepatomegaly, but it is more common in children; acute schistosomiasis is another option but is not endemic in Peru. Amebic liver abscess tends to present as a single lesion and is not associated with eosinophilia. This patient’s abdominal CT scan shows ill-defined areas of low attenuation and hypodense areas inside the liver. The rounded lesions are non-specific and cannot be distinguished from neoplasms or either pyogenic or amebic liver abscesses; the presence of tortuous channels make fascioliasis the leading diagnosis [J Radiol Case Rep 2019;13:11-16; J Med Case Rep 2021;15:324]. Hepatic calcifications as sequelae of massive hepatic infestation have been previously reported (See Gorgas Case 2005-02).

The mature adult parasites of F. hepatica usually inhabit the large biliary ducts. Eggs produced by the hermaphroditic adults pass with the feces and hatch, releasing larvae in fresh water. As with all other trematodes, F. hepatica requires a snail intermediate host. After passing through the snail, mature cercariae emerge and rapidly encyst on various kinds of aquatic vegetation. Our patient remembers eating watercress and lettuce, and drinking a local beverage made from alfalfa. After ingestion of infected aquatic vegetation or even water by a human or animal definitive host, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum, and the larvae penetrate the intestinal wall. They subsequently migrate directly into the liver via Glisson’s capsule and embark on a destructive migratory process through the hepatic parenchyma for 3 to 4 months, until they reach large biliary ducts where they mature into adults.

The mature adults range from 1 to 3 cm in length and attach to the biliary epithelium by a single ventral sucker. In the absence of direct visualization of adults, characteristic eggs can be seen on stool examination, but more often patients present in the early migratory phases of infection prior to maturation of the worm and the onset of egg-laying.

The distribution of F. hepatica is cosmopolitan, but it is by far most common in cattle-raising areas, where cows are common definitive hosts. Other important definitive hosts are goats, sheep, horses, llamas, vicunas, and camels. The contiguous Altiplano regions of the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes are highly endemic, with human prevalence rates as high as 67% in some villages. In the agricultural areas near Cuzco, the prevalence in children 3 to 12 years old is 11% by stool microscopy and Fas2-ELISA [Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Nov;91(5):989-93]. Fascioliasis has been also found in the jungle of Peru [Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;94:1309]. Egypt, Cuba, and Northern Iran are also highly endemic and the parasite is emerging in Vietnam and Cambodia. Cooking, which would kill the metacercariae, dramatically changes the flavor of watercress and the population is reluctant to adopt this simple measure. Emoliente, a local tea-like drink that uses drops of watercress and alfalfa juice to provide a bitter flavor is a frequent vehicle of infection.

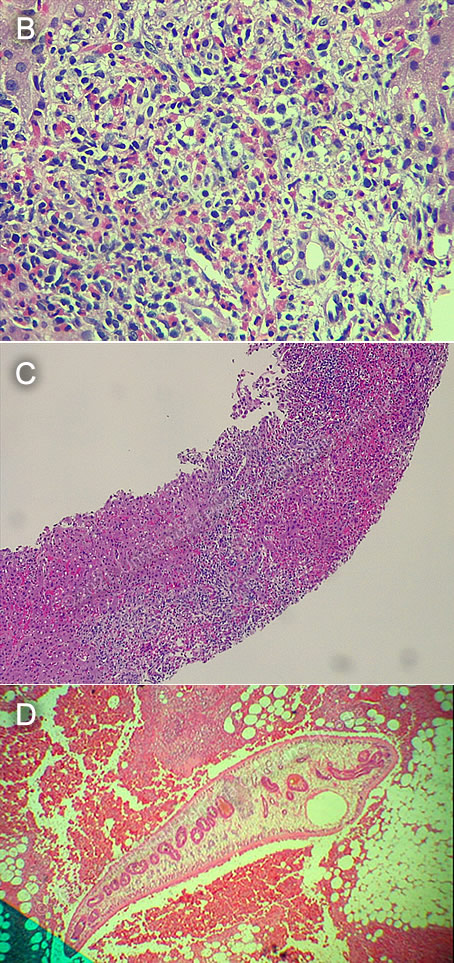

Clinically, the disease can be divided into acute and chronic phases. During the acute phase, migrating parenchymal larvae generally cause fever, eosinophilia, right upper quadrant pain and especially significant anorexia. Image D (from Gorgas Case 2015-05) shows a typical larva in a liver biopsy. Vomiting and weight loss of 20 kg or more may develop, which usually abate when the larvae mature to adults. Our patient initially did not mention any abdominal complaints, but upon further questioning, he reported mild and intermittent diffuse abdominal pain for at least two months before the diagnosis of the malignancy. The adult flukes in the biliary tree are generally asymptomatic but some patients develop chronic manifestations including right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, and hepatomegaly. Eosinophilia and abnormal liver function may develop but are less common than with acute disease. Adult flukes may cause hyperplasia, desquamation, thickening, and dilatation of the bile ducts. Malignant degeneration and cholangiocarcinoma such as result from chronic infection with the oriental liver fluke Clonorchis sinensis has not been reported with F. hepatica. However, liver fibrosis and liver cirrhosis have been reported with chronic Fasciola infection [Plos Negl Trop Dis 2016;10:e0004962]. We have reported a case series with clinical findings and evolution of disease [Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Feb;78(2):222-7]. Please see Gorgas Case 2005-02 and Gorgas Case 2015-05 for CT images of other examples with the typical larval tracks seen in acute disease.

There is no gold standard for the diagnosis of fascioliasis. Stool microscopy is frequently used in endemic countries, as finding eggs in the stool can provide a diagnosis. However, it has a low sensitivity in the acute phase, as parasites do not produce eggs during tissue migration. During the chronic phase, diagnosis by stool microscopy requires multiple samples and special concentration methods, as the distribution of parasite eggs in the stool may not be uniform, and egg excretion may not be consistent. Low egg counts may also be found in long-term infections, cases of treatment failure, or infections with hybrid parasites (F. hepatica/F. gigantica) [Res Rep Trop Med 2020;11:149-158]. Direct observation of the parasites using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), can also be helpful in establishing a diagnosis, but it is not essential. F. hepatica flukes are small, leaf-like and flat, and are often confused with bile stones. They are usually found in the gallbladder or dilated bile ducts, and can frequently be physically extracted, providing symptom relief. Antibody testing using ELISA directed to surface antigens is the preferred diagnostic method with high reported sensitivity and specificity values. Lack of availability of these serologic methods in highly endemic areas complicates the proper diagnosis and initiation of treatment. New diagnostic methods using molecular techniques are promising with the potential of use in stool and serum samples [Res Rep Trop Med 2020;11:149-158].

Fasciola hepatica is the only trematode infection for which praziquantel is not the drug of choice. The WHO has included the anthelmintic triclabendazole (Egaten, Novartis) on its essential drugs list, and recommends treatment with a single dose of 10mg/kg, given with foods. A second dose is only recommended in cases of treatment failure. Egaten is registered in Peru (as in Mexico and Egypt) and is available via free donation from the WHO. In the US, triclabendazole was approved for the treatment of fascioliasis by the FDA in 2019, with a recommended regimen of 2 doses of 10mg/kg given 12 hours apart. Egaten can be sent for free anywhere in the US by contacting Novartis. In initial studies at our institute, the cure rate was 96%, but this rate has been lower in more recent studies, suggesting resistance to triclabendazole [PloS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10:e0004361: Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018 Oct;31(5):409-414].

Treatment with triclabendazole 10 mg/kg in a single dose will be given to this patient. However, the drug is currently hard to obtain in Peru due to lack of importation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

|